International election observers evaluating US midterm elections will face limitations

- Written by Judith Kelley, Dean of the Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, or OSCE, is sending[1] international election observers to the 2018 U.S. midterm election.

American voters may be surprised to learn such visits are routine. In fact, this will be the seventh such visit since 2002.

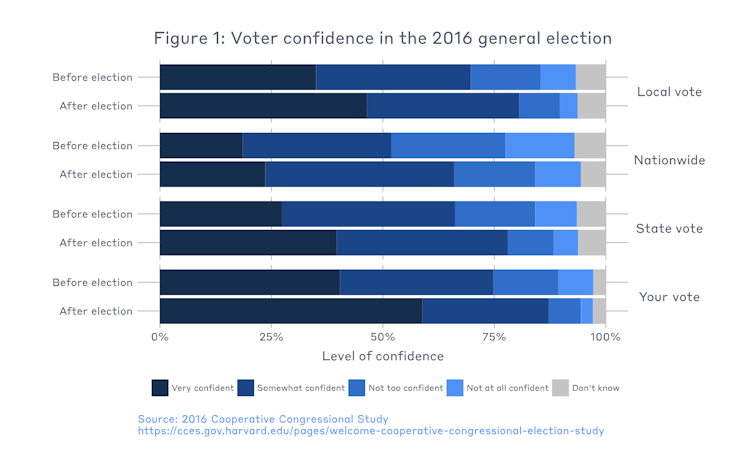

This year, with the ongoing Mueller probe about election meddling and concerns about cybersecurity, the election observers are likely to encounter a growing climate of distrust among U.S. voters about elections and the voting process.

A growing practice

As I describe in my book “Monitoring Democracy[2],” international election observers are representatives from intergovernmental organizations or nongovernmental organizations from other countries. They monitor elections during the pre-election period, on election day and during the post-election period.

The OSCE, created in 1972, is one of the most active groups that monitors elections around the world. All 57 member states, including the U.S., have agreed to allow the OSCE to monitor their elections.

Election monitoring has grown dramatically since the end of the Cold War. At first, election monitors focused on emerging democracies such as those in Eastern Europe. But in an effort to be more egalitarian, observation missions to established democracies such as the United States have become common.

Monitoring teams usually fan out across the country and compile their observations into national reports. They make recommendations not only about the conduct of the polling, but also about the electoral system and political environment more broadly.

Hacking and disenfranchisement

In the 2016 general U.S. elections, OSCE observers praised the integrity and conduct[3] of voting, but raised concerns about the candidates’ campaigns using “harsh personal attacks.” They also noted voting rights were denied to some citizens, due to “recent legal changes and decisions on technical aspects of the electoral process [that] were often motivated by partisan interests.” Some of the OSCE recommendations have been addressed. For example, the 2018 pre-election assessment noted that “there is an emerging trend among states to ease restrictions on the restoration of voting rights for ex-prisoners, in line with prior OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights recommendations.”

MIT Election Lab[4]

Still, two years later, many of the concerns from the 2016 report remain. In June 2018, the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights said its U.S. midterm election monitors should focus on[5] concerns about “voter rights, registration and identification, security of election technologies, alternative voting methods, campaign finance, and the conduct of the electoral campaign, particularly online and in the media.”

Traditional voter fraud, such as impersonation at the polls, is rare[6]. Instead, Americans are worried about hacking[7] and disenfranchisement – voters having their ballots disqualified or being prevented or discouraged from voting at all.

For example, civil rights groups in Georgia sued[8], arguing that a voter registration law requiring an “exact match” between a registration form and voter’s existing identification suppressed minority votes. In Florida, Georgia and North Carolina[9] rising rates of voter registration purges have raised concerns that people – again mostly minority voters – might be removed without justification. And in other states extreme gerrymandering[10] leads some voters to think their votes are unimportant, because even large changes in the votes a party receives can lead to no change in the number of seats that party wins.

Limited scope

My own research[11], as well as that of others, has found that election observers[12] can – under some conditions – lead to improvements in conduct and quality of elections.

However, this year’s mission to the U.S. will be small. The 2016 U.S. general election had 400 observers.

Because it is a midterm election, the 2018 mission will feature only 13 international experts in Washington, D.C., plus 36 observers who will go to locations throughout the country.

The observers also are limited in where they can go. Although all OSCE member nations are obligated to allow observers to visit their elections, 12 U.S. states – including Alabama, Florida and Ohio – actually prohibit[13] the presence of international observers. This is possible because election laws are made at the state level in the United States, and states have varied preferences. Instead, these states only allow party or candidate-affiliated observers[14] from their own state.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision[15] to strike down parts of the Voting Rights Act has reduced domestic election oversight. Previously, the federal Department of Justice had to review proposed election law changes in 15 states – in whole or in part – where history suggests racial discrimination might occur. Many, but not all, of the supervised jurisdictions were in the South.

While the United States has been on the forefront of sending various observer missions to other countries, the OSCE is the only serious group that conducts international election observation in the United States. With such a small mission, their influence will be limited.

As a result, their presence and insights are likely to remain, as they have in past U.S. elections, largely under the radar, stimulating discussion mostly among insiders. Still, such discussion can be valuable to signal to other countries that the U.S. is willing to hold itself accountable for its electoral integrity.

MIT Election Lab[4]

Still, two years later, many of the concerns from the 2016 report remain. In June 2018, the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights said its U.S. midterm election monitors should focus on[5] concerns about “voter rights, registration and identification, security of election technologies, alternative voting methods, campaign finance, and the conduct of the electoral campaign, particularly online and in the media.”

Traditional voter fraud, such as impersonation at the polls, is rare[6]. Instead, Americans are worried about hacking[7] and disenfranchisement – voters having their ballots disqualified or being prevented or discouraged from voting at all.

For example, civil rights groups in Georgia sued[8], arguing that a voter registration law requiring an “exact match” between a registration form and voter’s existing identification suppressed minority votes. In Florida, Georgia and North Carolina[9] rising rates of voter registration purges have raised concerns that people – again mostly minority voters – might be removed without justification. And in other states extreme gerrymandering[10] leads some voters to think their votes are unimportant, because even large changes in the votes a party receives can lead to no change in the number of seats that party wins.

Limited scope

My own research[11], as well as that of others, has found that election observers[12] can – under some conditions – lead to improvements in conduct and quality of elections.

However, this year’s mission to the U.S. will be small. The 2016 U.S. general election had 400 observers.

Because it is a midterm election, the 2018 mission will feature only 13 international experts in Washington, D.C., plus 36 observers who will go to locations throughout the country.

The observers also are limited in where they can go. Although all OSCE member nations are obligated to allow observers to visit their elections, 12 U.S. states – including Alabama, Florida and Ohio – actually prohibit[13] the presence of international observers. This is possible because election laws are made at the state level in the United States, and states have varied preferences. Instead, these states only allow party or candidate-affiliated observers[14] from their own state.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision[15] to strike down parts of the Voting Rights Act has reduced domestic election oversight. Previously, the federal Department of Justice had to review proposed election law changes in 15 states – in whole or in part – where history suggests racial discrimination might occur. Many, but not all, of the supervised jurisdictions were in the South.

While the United States has been on the forefront of sending various observer missions to other countries, the OSCE is the only serious group that conducts international election observation in the United States. With such a small mission, their influence will be limited.

As a result, their presence and insights are likely to remain, as they have in past U.S. elections, largely under the radar, stimulating discussion mostly among insiders. Still, such discussion can be valuable to signal to other countries that the U.S. is willing to hold itself accountable for its electoral integrity.

References

- ^ is sending (www.osce.org)

- ^ Monitoring Democracy (press.princeton.edu)

- ^ praised the integrity and conduct (www.osce.org)

- ^ MIT Election Lab (electionlab.mit.edu)

- ^ said its U.S. midterm election monitors should focus on (www.osce.org)

- ^ is rare (www.brennancenter.org)

- ^ hacking (www.vox.com)

- ^ civil rights groups in Georgia sued (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ In Florida, Georgia and North Carolina (www.brennancenter.org)

- ^ extreme gerrymandering (www.brennancenter.org)

- ^ My own research (sites.duke.edu)

- ^ election observers (www.cambridge.org)

- ^ 12 U.S. states – including Alabama, Florida and Ohio – actually prohibit (www.ncsl.org)

- ^ party or candidate-affiliated observers (www.ncsl.org)

- ^ Supreme Court’s 2013 decision (www.washingtonpost.com)

Authors: Judith Kelley, Dean of the Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University