My research helped uncover a long-lost right-wing provocateur – but then I turned away from her work

- Written by Carole Sargent, Literary Historian; Founding Director of the Office of Scholarly Publications, Georgetown University

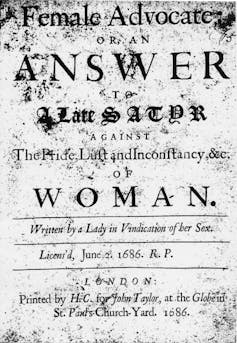

Years ago I discovered a shocking early English political satirist when a professor urged me not study her. Dismissing what I assumed was his liberal bias, I claimed bipartisan curiosity and dove in anyway. You could say I fell for the clickbait.

What I found went beyond politics. To explain why I later stopped studying her, I said she sounded like “the Ann Coulter of 1709,” after the modern right-wing commentator. The satirist, London playwright Delarivier Manley, wrote and flourished between 1690 and 1720. In 1709 she anonymously published “The New Atalantis,” two bestselling books packed with behind-the-scenes political scandals. This gossipy, libelous attack included sex and humor.

Political conservatives like her were called Tories, then an emerging party. Also known as “royalists,” they stood for a powerful throne, an archbishop-controlled Church of England and nobility ruling the working class. The opposing faction, Whigs, were rough equivalents of today’s British Labour party, leaning toward what became representative government with a prime minister. Literary scholar Rachel Carnell’s new book “Backlash: Libel, Impeachment, and Populism in the Reign of Queen Anne[1],” with images from my collection of Manley’s books, offers context for that complex time.

The American colonies weren’t yet a country, and their leaders followed London news. As an early Americanist studying English women writers’ influence on our shores, I noted William Byrd II, founder of Richmond, Virginia, staying up nights decoding Manley’s books[2].

Manley’s opinions seemed like standard Tory politics, so at first I didn’t see a problem. As I decoded more stories, however, a disturbing subtext emerged.

Pie-throwing in an old English ballad, ‘The Counter-Scuffle,’ by Robert Speed (London: William Butler, 1621).

Carl H. Pforzheimer Library, Harry Ransom Center, Pforz App. 10 PFZ.[3]

Pie-throwing in an old English ballad, ‘The Counter-Scuffle,’ by Robert Speed (London: William Butler, 1621).

Carl H. Pforzheimer Library, Harry Ransom Center, Pforz App. 10 PFZ.[3]

Brilliant disguises

I missed her more extreme points because she wrote in a kind of storybook code. Strict libel laws might land a writer in prison, so she couldn’t attack directly. Instead, Manley used popular songs and fables[4] as strategic cover. When she was arrested, she claimed ignorance and avoided prison.

In one scene I decoded, a poet wife smacks her priest husband in the face with a hot apple pie, followed by butter “to cool him again.” The scene was vague enough for her to plausibly deny any connection to real people, even under oath in court. Within a generation few understood it.

Three centuries later, I used 21st-century technology to decipher it[5]. Working with a database of 18th-century texts[6], which computers have only recently been able to scan, and using clues in a footnote from literary scholar Ros Ballaster of Oxford, I searched “pye” (their spelling), “butter” and stories of wives beating husbands.

Manley borrowed both characters from famous ballads to disguise a well-known, divorcing couple. She accused the wife, poet Sarah Fyge Egerton, and her rich Whig patrons of being what we now call feminists. Modern far-right provocateur Ann Coulter dubs them “angry, man-hating lesbians[7],” and Manley later used the charge of lesbianism as a similar political cudgel. Women’s sexual empowerment became a weapon – pie – upending both the poet’s marriage and the order of the Church of England.

Humor can normalize bigotry

Feminist poems like this drew Manley’s satiric fire.

Sarah Fyge Egerton, via Wikimedia Commons[8]

Feminist poems like this drew Manley’s satiric fire.

Sarah Fyge Egerton, via Wikimedia Commons[8]

Manley was an entertaining writer, memorably commenting on controversial issues while escaping serious punishment. But as my digging revealed coded racism, antifeminism, homophobia and fear of immigration, I reconsidered my priorities.

She admitted that she was “a perfect bigot[9],” citing “untainted” lineage. In another story I decoded, she portrayed the new Bank of England in dangerous debt to foreign lenders[10]. She warned they would foreclose, steal jobs, marry into the aristocracy and rule Britannia. Her warnings also influenced American colonial leaders.

Gradually I understood why Winston Churchill had railed against her. Though he was no champion for immigrants[11], he deplored her tactics. Manley insulted his ancestor the duke of Marlborough, saying he prostituted himself to a king’s mistress to buy his military commission. She also claimed Marlborough prolonged a war for personal gain, and bet on the outcome of battles he commanded. Churchill wanted to sweep her “back to the cesspool from which she should never have crawled[12].”

Whoopi Goldberg confronts Ann Coulter on ‘The View’ in 2012.The charm offensive

I met Ann Coulter at the National Press Club. She was friendly, but why not? Manley also had personality. Jonathan Swift, famed author of “Gulliver’s Travels” and “A Modest Proposal,” dined with her and hired her to edit his Tory newspaper one summer. But Swift eventually distanced himself[13], complaining Manley ranted too much. Similarly, the conservative magazine National Review dropped Coulter’s column[14] after her post-9/11 call to “invade (Muslim) countries, kill their leaders, and convert them to Christianity.”

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[15].]

Manley’s will requested her papers be burned, “that none ghost like may walk after my decease[16],” but her spirit still rattles around. In 2016 her wraith must have howled in glee over Brexit. In early 2017 I thought I heard her cheering when the immigrant-loathing United States president initiated a Muslim ban[17].

Instead of Manley, I now study a Whig poet who was influential in early America, Elizabeth Singer Rowe. If my identification of her in “The New Atalantis” is correct, then Manley attacked her for being a closeted lesbian. I anticipate bringing her, Sarah Fyge Egerton and others to vivid political life for a new generation of readers.

References

- ^ Backlash: Libel, Impeachment, and Populism in the Reign of Queen Anne (www.upress.virginia.edu)

- ^ staying up nights decoding Manley’s books (books.google.com)

- ^ Carl H. Pforzheimer Library, Harry Ransom Center, Pforz App. 10 PFZ. (www.dropbox.com)

- ^ used popular songs and fables (publons.com)

- ^ I used 21st-century technology to decipher it (www.academia.edu)

- ^ database of 18th-century texts (textcreationpartnership.org)

- ^ angry, man-hating lesbians (youtu.be)

- ^ Sarah Fyge Egerton, via Wikimedia Commons (commons.wikimedia.org)

- ^ a perfect bigot (books.google.com)

- ^ debt to foreign lenders (doi.org)

- ^ Though he was no champion for immigrants (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ back to the cesspool from which she should never have crawled (www.english-heritage.org.uk)

- ^ But Swift eventually distanced himself (books.google.com)

- ^ National Review dropped Coulter’s column (www.nationalreview.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ that none ghost like may walk after my decease (books.google.com)

- ^ initiated a Muslim ban (www.aclu-wa.org)

Authors: Carole Sargent, Literary Historian; Founding Director of the Office of Scholarly Publications, Georgetown University