The Black Church has been getting 'souls to the polls' for more than 60 years

- Written by David D. Daniels III, Professor of Church History, McCormick Theological Seminary

At Black churches up and down the U.S., religious slogans have been supplanted with another message in the run up to Nov. 3: Vote!

The landscape of the 2020 general election has been dotted with efforts by the Black Church[1] – churches that have traditionally had predominantly African American congregation – to encourage voter registration, mobilization and protect against efforts to suppress the vote.

Under slogans including “Souls to the Polls[2],” “AME Voter Alert[3]” and “COGIC Counts[4],” Black denominations and national bodies such as the Conference of National Black Churches have partnered with civil rights organizations including the NAACP in a concerted effort to increase voter turnout among African Americans.

The push comes amid deliberate tactics to make it harder[5] for Black and Latino Americans to vote, including purges of voter rolls[6] in communities of color, strict voter ID rules[7] and restrictions on polling places[8]. As a historian[9], I know these tactics are nothing new – nor is the role of Black Churches in countering these moves.

Black Church-led campaigns to expand and protect voting among African American reaches back to the years following the Civil War[10]. At political forums held in churches, clergy educated congregants on political issues, regularly running for elected office themselves.

‘Give us the ballot’

Modern efforts picked up momentum during the years after World War II, especially during the era of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Most African Americans were denied the right to vote[11] prior to the 1965 Voting Rights Act[12] being signed into law. As a result, Black Americans were grossly underrepresented in the political system while simultaneously marginalized within the economy and social order through racial segregation laws.

In 1957, churches and civil rights organizations got together to sponsor the “Prayer Pilgrimage of Freedom[13]” demonstration in Washington D.C. Organized to celebrate the third anniversary of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, which ruled school segregation unconstitutional, the event became a rallying cry for voting rights.

Speaking at the Lincoln Memorial, Martin Luther King Jr. framed the issue of voting, racial progress, and democracy in these terms[14]:

“Give us the ballot and we shall no longer have to worry the Federal government about our basic rights.

"Give us the ballot and we will by the power of our vote write the laws on…the statute books of the southern states and bring to an end the dastardly acts of the hooded perpetrators of violence.

"Give us the ballot and we will fill our legislative halls with men of goodwill.

"Give us the ballot and we will place judges on the benches of the South who will do justly and have mercy.”

The speech came at a time when barriers to Black voting [15] ranged from poll taxes, literacy tests to the use of voter intimidation.

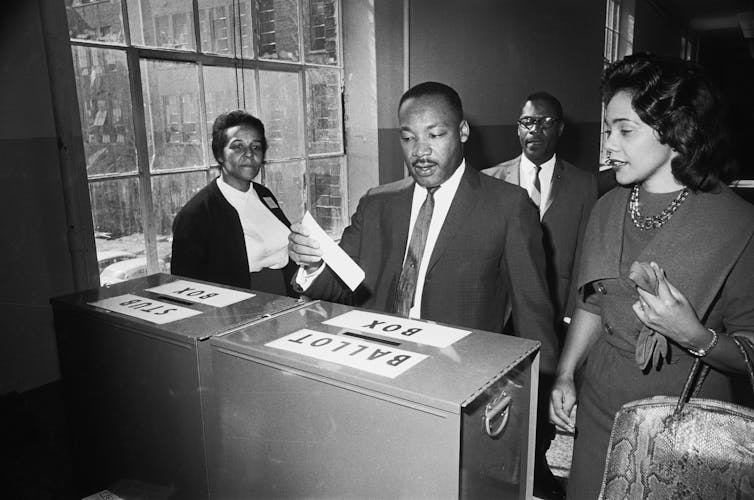

Martin Luther King Jr. saw the Black Church as a key player in encouraging voter registration.

Bettmann/Getty Images[16]

Martin Luther King Jr. saw the Black Church as a key player in encouraging voter registration.

Bettmann/Getty Images[16]

To King and other civil rights leaders, the Black Church was a key institution within the pro-democracy movement[17]. They believed its reach could be harnessed to eradicate the barriers to voting and expand accessibility of voting and enlarge the number of voters.

Rise of the PACs

A lot of Black Church-based voter registration efforts in the following decades took place under the Voter Education Project[18], which lasted from 1962 to 1992. The project sponsored citizenship education, voter registration and mobilization, as well as research on voting among African Americans.

Black denominations such as the African Methodist Episcopal Church also worked alongside black sororities and fraternities, civil rights agencies, masonic lodges and labor unions in voter projects such as “Operation Big Vote” and “Wake Up, Black America” to encourage voter turnout.

Meanwhile churches often served as locations for voter registration strategy meeting and forums.

In addition to the Voter Education Project, churches and civil rights organizations worked together to set up political action committees to push for voting rights. Political scientist Ronald E. Brown[19] has described how[20] in cities like Detroit, The Black Slate Political Action Committee[21] and The Fannie Lou Hamer Political Action Committee[22] were established as “church-based political action committees” advocating “on behalf of the poor and powerless during electoral campaigns.”

These PACs emerged during the 1970s and 1980s. They led voter registration and turn-out campaigns, provided education on political issues and endorsed candidates. Both remained active even into the 2020 general election cycle.

The “Souls to the Polls” movement began in Florida during the 1990s[23]. The concept was to organize caravans after church service on the Sunday prior to Election Day to transport Black congregants to early voting locations. By the early 2000s, the NAACP, Black denominations and other organizations had transformed “Souls to the Polls” into a national movement.

Record turnout

Such initiatives along with the passing of the Civil Rights Act helped increase national Black voter turnout from 40% in 1960 to 60% in 1984, according to political scientist Zulema Blair[24].

Obama’s re-election garnered the highest percentage of Black voter turnout, reaching 66.6% of eligible Black voters in 2012[25]. This was 1 percentage point higher than the actual white voter turnout – a new threshold for Black voter mobilization.

But with the U.S. Supreme Court eliminating part of the Voting Rights Act[26] in 2013, Black Church-based voter registration and “turnout the votes” campaigns have been hampered by voter suppression efforts that have included new voter ID requirements[27], the reducing of early voting days, the ending of same-day registration, the disenfranchisement of citizens with felony records [28], and the closing of over 1,600 polling sites [29] across the nation.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[30].]

The voter suppression has kick-started a renewed focus on protecting the right to vote in addition to voter registration and mobilization spearheaded by organizations such as the Black Church PAC[31] and Black denominations such as the African Methodist Episcopal, Full Gospel Baptist, Church of God in Christ, and Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Meanwhile, the Conference of National Black Churches along with advocacy groups the National Action Network and The Collective have launched “Black Church 75[32]” – which aims to get 75% of all Black church members registered to vote.

With a dual approach of concentrating on the 2020 general election and future planning for the 2022 and 2024 elections, the Black Church continues to work to expand and strengthen democracy in the United States, tapping into its rich history of securing voting rights for all U.S. citizens.

References

- ^ dotted with efforts by the Black Church (apnews.com)

- ^ Souls to the Polls (www.wuft.org)

- ^ AME Voter Alert (www.ame-church.com)

- ^ COGIC Counts (www.cogic.org)

- ^ deliberate tactics to make it harder (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ purges of voter rolls (www.nbcnews.com)

- ^ strict voter ID rules (doi.org)

- ^ restrictions on polling places (publicintegrity.org)

- ^ a historian (mccormick.edu)

- ^ years following the Civil War (www.jstor.org)

- ^ denied the right to vote (www.epi.org)

- ^ 1965 Voting Rights Act (www.ourdocuments.gov)

- ^ Prayer Pilgrimage of Freedom (kinginstitute.stanford.edu)

- ^ in these terms (kinginstitute.stanford.edu)

- ^ barriers to Black voting (www.umich.edu)

- ^ Bettmann/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ key institution within the pro-democracy movement (doi.org)

- ^ Voter Education Project (kinginstitute.stanford.edu)

- ^ Ronald E. Brown (clasprofiles.wayne.edu)

- ^ described how (www.cus.wayne.edu)

- ^ Black Slate Political Action Committee (www.transparencyusa.org)

- ^ The Fannie Lou Hamer Political Action Committee (flhpac.org)

- ^ began in Florida during the 1990s (www.miamiherald.com)

- ^ according to political scientist Zulema Blair (digitalscholarship.tsu.edu)

- ^ eligible Black voters in 2012 (www.pewresearch.org)

- ^ Voting Rights Act (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ voter ID requirements (publicintegrity.org)

- ^ disenfranchisement of citizens with felony records (www.aclu.org)

- ^ closing of over 1,600 polling sites (www.motherjones.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ Black Church PAC (www.blackchurchpac.org)

- ^ Black Church 75 (www.blackchurch75.org)

Authors: David D. Daniels III, Professor of Church History, McCormick Theological Seminary