When plants and their microbes are not in sync, the results can be disastrous

- Written by Sheng-Yang He, University Distinguished Professor, HHMI Investigator, Michigan State University

Many of us have heard about inflammatory bowel disease[1], a debilitating condition that is associated with an abnormal collection of microbes in the human gut – known as the gut microbiome. My lab[2] recently found that, like humans, plants can also develop this condition, known as dysbiosis, with severe consequences.

As part of this study[3], my colleagues and I discovered that some genes and processes involved in controlling dysbiosis in plants may be similar to those in humans. Discovery of dysbiosis in the plant kingdom opens new possibilities for stimulating innovation in plant health and global food security.

I am a plant microbiologist[4] interested in how plants and microbes interact with each other. Although our research in the past has centered on molecular details of pathogenic infections[5], this work led my lab into the fascinating world of plant microbiome.

Do plants have microbiomes?

When scientists say that human “gut bacteria” should be well balanced, they are referring to the genetic material of all the microbes living in human digestive systems, or the gut microbiome. Do plants have microbiomes as well? The answer is yes.

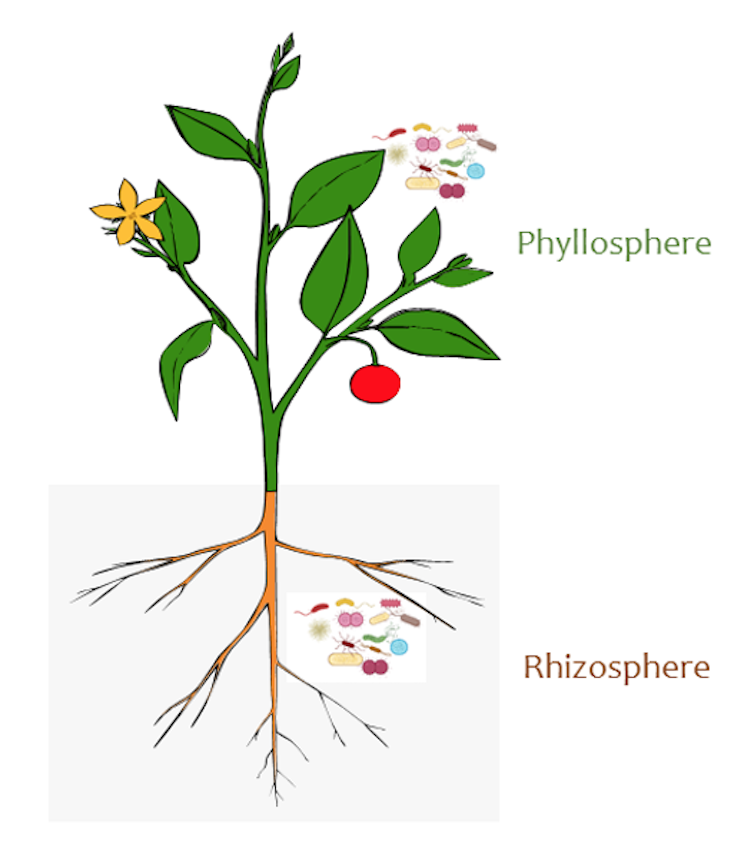

In fact, the parts of the plant that grow aboveground, called phyllosphere, and those parts that grow below, called rhizosphere, provide one of the largest habitats for microbe colonization on Earth. Both are vital for human life on Earth.

The phyllosphere takes up carbon dioxide for photosynthesis, which is necessary to build biomass and is a primary source of food, fuels, fibers and medicines. Photosynthesis also releases oxygen for animals and humans to breathe, which is why plants are often considered to be the lungs of our planet. The rhizosphere, on the other hand, takes up water and nutrients from soil.

Numerous studies[6] have shown that plant microbes help plants extract nutrients from the soil and cope with drought, pathogens, insects and other stresses.

Ecological studies[7] have also noted that the greater diversity of microbes living on plant leaves, the more productive the plants seem to be.

Today, most plant scientists believe global strategies to ensure crop productivity and food security must consider plants’ microbiome. The U.N.‘s Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that up to 40% of food crops[8] are lost due to plant pests and diseases annually, and the United Nations General Assembly declared 2020 as the International Year of Plant Health.

Some microbes are associated with the leaves and shoots, while another distinct set live among the roots.

Sheng-Yang He, CC BY-SA[9]

Some microbes are associated with the leaves and shoots, while another distinct set live among the roots.

Sheng-Yang He, CC BY-SA[9]

How do plants keep microbiota healthy?

Given the importance of microbiota – the specific community of microbes living on or near plants – for plant health, we reasoned that plants must have evolved a sophisticated genetic network to select the right mix of microbes.

If that is true, then knowing which plant genes influence the types of microbes surrounding the plant could guide future research to optimize plant microbiomes to help plants grow better, stronger and to produce more biomass and yield.

Indeed, my group has now identified some of these “microbiota-controlling” genes in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana.

We found that several genes[10] involved in plant immunity and water balance are critical for selecting and maintaining a healthy microbiota inside Arabidopsis plant leaves.

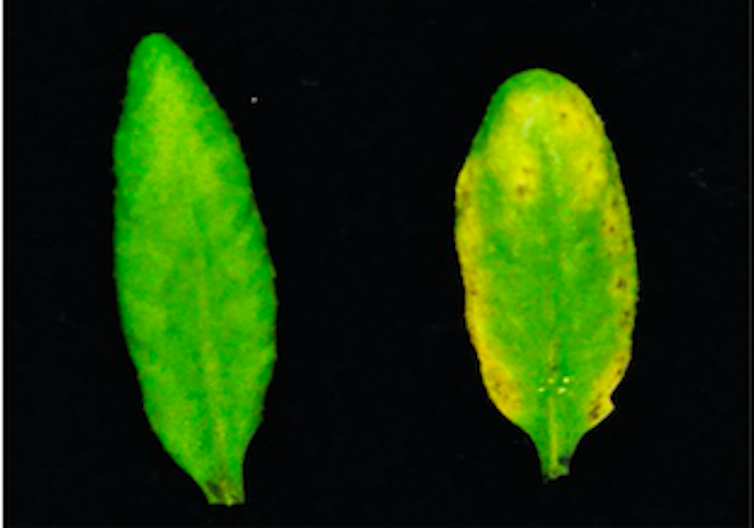

When we removed these identified genes from plants, the Arabidopsis plant mutants could not host the correct mix of microbes and displayed symptoms of dysbiosis, including dead or yellowing leaves. As far as we know, this was the first time the negative effects of dysbiosis have been causally documented[11] in the plant kingdom.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter[12].]

Interesting features of ‘sick’ plants

My colleagues and I observed some notable dysbiosis features in our mutant Arabidopsis plants.

First, dysbiosis mutants tend to have an abnormally high level of microbes living inside the leaves.

A leaf from a healthy Arabidopsis plant (left) and a leaf from a dysbiosis mutant plant (right).

Sheng-Yang He, CC BY-SA[13]

A leaf from a healthy Arabidopsis plant (left) and a leaf from a dysbiosis mutant plant (right).

Sheng-Yang He, CC BY-SA[13]

Second, there is a drastic change in the diversity of microbes. For example, in normal Arabidopsis plant leaves, there are all kinds of bacteria living inside the leaf. In contrast, overall diversity of bacteria is greatly reduced in the dysbiotic mutants, suggesting that healthy plants promote microbial diversity, presumably to increase the benefits to plant health.

Third, while bacteria that belong to the phylum Fermicutes are abundant inside wild-type Arabidopsis leaves, the abundance is significantly reduced in our genetic mutants. In addition, we saw a dramatic increase in the number of harmful bacteria inside the dysbiosis mutant leaves. We find it interesting that some of these microbiota changes are also observed in inflammatory bowel disease human patients, suggesting conceptual parallels in the development of dysbiosis in humans and plants.

What’s next?

We are excited about our identification of several plant genes and processes involved in preventing dysbiosis. The microbiota-controlling genes we identified in Arabidopsis are found in the genomes of many other plants, suggesting our findings may have broad applicability.

In the future, we could experiment with changing these host genes, which may lead to microbiota-based approaches that improve plant health. For example, gene-editing technologies could be used to create a healthy biome in plant leaves by enhancing expression of specific genes. A synthetic healthy microbiome may be formulated as a probiotic to prevent dysbiosis in plants, much as probiotics have been promised to improve human gut microbiome health[14].

Of note, mutations in genes related to a person’s immune system, are a well-known risk factor for the development of inflammatory bowel disease[15] in humans. Perhaps, future research will find more shared characteristics in how plants and humans interact with their respective microbiota in order to prevent disease.

The ease of genetic studies in plants, such as Arabidopsis, also offers the possibility that researchers will be able to identify more genes involved in preserving microbiota health in people and plants.

References

- ^ inflammatory bowel disease (www.niddk.nih.gov)

- ^ My lab (www.thehelab.org)

- ^ this study (doi.org)

- ^ I am a plant microbiologist (doi.org)

- ^ molecular details of pathogenic infections (doi.org)

- ^ Numerous studies (doi.org)

- ^ Ecological studies (doi.org)

- ^ up to 40% of food crops (www.fao.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ We found that several genes (doi.org)

- ^ first time the negative effects of dysbiosis have been causally documented (doi.org)

- ^ Read The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ probiotics have been promised to improve human gut microbiome health (www.genome.gov)

- ^ risk factor for the development of inflammatory bowel disease (doi.org)

Authors: Sheng-Yang He, University Distinguished Professor, HHMI Investigator, Michigan State University