Federal executions to resume, posing a new test for lethal injection

- Written by Austin Sarat, Associate Provost and Associate Dean of the Faculty and Cromwell Professor of Jurisprudence and Political Science, Amherst College

Now that the U.S. Supreme Court has refused to hear four inmates’ challenge[1] to the specifics of the lethal injection process, federal executions are expected to resume[2] next week. In July 2019, Attorney General William Barr declared an end to a federal moratorium on executions[3] that had been in effect since 2003.

The inmates alleged[4] that the Justice Department’s execution instructions[5], which call for the use of a single dose of pentobarbital[6], a barbiturate that is normally used as a sedative, violates the Federal Death Penalty Act[7].

They claimed that the law requires federal executions to be carried out “in the manner prescribed by the state” in which the prisoner was convicted. Pentobarbital is not used in Arkansas, Iowa or Missouri, the pertinent states in their cases. They were hoping their executions would have to be carried out using drugs the federal government does not possess, sparing them at least temporarily.

My research on America’s methods of execution[8] indicates that the promised benefits of lethal injection – a quick, painless death – have never come true. And there is no longer a national consensus about what drugs, or drug combinations, are best for putting people to death.

The history of lethal injection

Lethal injection has been legal in the U.S. since 1977, although its history can be traced back to the late 19th century.

At that time, a state commission in New York looked at alternatives to hanging[9], which was then the most common method of execution. Hanging had been discredited because of several gruesome botched executions. The commission discussed lethal injection, but the state ultimately chose electrocution as its preferred method.

In 1953, Great Britain’s Royal Commission on Capital Punishment[10] also considered lethal injection as a possible replacement for the gallows, but ultimately chose not to recommend its use. The Royal Commission heeded medical experts’ warnings that the drugs could cause problems and that it might be hard to find the veins of the condemned – fears that have become reality in the U.S. in recent years.

[Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get expert takes on today’s news, every day.[11]]

Others have continued to advocate for lethal injection – including people who oppose government executions altogether. Albert Camus, the French philosopher who was one of the 20th century’s leading opponents of the death penalty, famously argued that that if France was to continue using capital punishment, it should do so with “decency” by using an “anesthetic that would allow the condemned man[12] to slip from sleep to death.”

An 1834 depiction of the 1793 execution of French King Louis XVI shows the guillotine, once believed to be a more humane execution method but later viewed as barbaric.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images[13]

An 1834 depiction of the 1793 execution of French King Louis XVI shows the guillotine, once believed to be a more humane execution method but later viewed as barbaric.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images[13]

Replacing the electric chair

During the last quarter of the 20th century, similar beliefs[14] about the allegedly more humane nature of lethal injection surfaced in U.S. state legislative debates seeking an alternative to the electric chair.

Oklahoma became the first state formally to adopt lethal injection[15] as its method of execution. At the time, it chief legislative proponents claimed[16] that it would be a dramatic improvement over the “inhumanity, visceral brutality, and cost” of the electric chair.

Oklahoma chose lethal injection, as legal scholar Deborah Denno writes, “despite the fact that the procedure had never been medically or scientifically studied on human beings[17].”

By 2002, 20 years after Texas became the first state to carry out an execution by lethal injection, 37 states[18] had made it their default method.

How lethal injection works

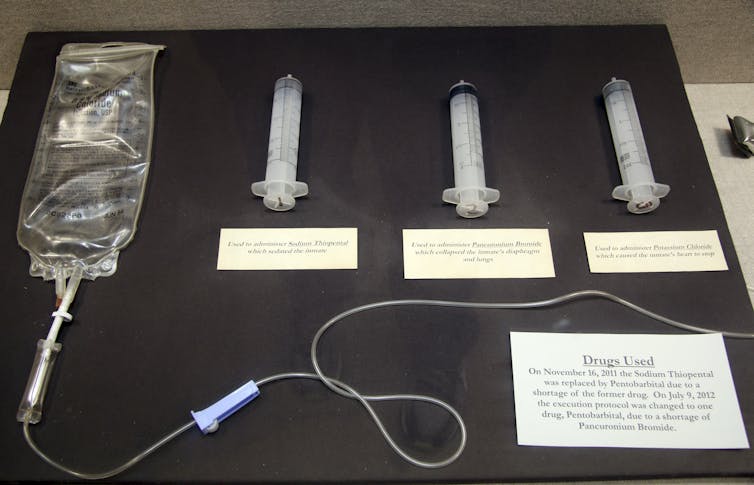

Over that period, a consensus emerged[19] among death penalty states about the exact mix of drugs that would be most effective. A three-drug protocol was developed, combining an anesthetic (usually sodium thiopental) with a paralytic agent (pancuronium bromide), and a drug to stop the heart (potassium chloride).

However, since 2010, shortages of those drugs have caused the consensus to disintegrate. Death penalty proponents complained that the shortages resulted from opponents’ efforts to end the death penalty by any means, saying the activists had pressured companies to stop making those drugs[20].

Complaints about an artificially created drug shortage also found their way onto the pages of Supreme Court opinions. In the 2015 Glossip v. Gross[21] decision upholding lethal injection, Justice Samuel Alito wrote that the court should not let condemned inmates delay their dates with death, because “anti-death-penalty advocates pressured pharmaceutical companies to refuse to supply the drugs used to carry out death sentences.”

States search for alternatives

Since 2010, states have gone their own ways[22] in search of supposedly humane and efficient methods for carrying out death sentences.

The Death Penalty Information Center, a national clearinghouse for analysis and information on issues concerning capital punishment, reports[23] that in the past decade eight states have used just one drug, usually a lethal dose of an anesthetic. Fourteen states have employed pentobarbital. Seven have used midazolam as part of a three-drug protocol. Nebraska has used fentanyl, a powerful opioid[24], and Nevada has authorized its use.

Other states have chosen nitrogen hypoxia[25], which an inmate inhales and which kills by depriving the body of oxygen, as an alternative to lethal injection. Additional alternatives condemned inmates can choose include the electric chair in Tennessee, firing squad in Utah and hanging in New Hampshire. Of these, only Tennessee’s electric chair[26] has been used recently.

A 2017 photo shows the three-chemical mixture used by Texas prison officials for lethal injections in the state from 1982 until 2012.

AP Photo/Michael Graczyk[27]

A 2017 photo shows the three-chemical mixture used by Texas prison officials for lethal injections in the state from 1982 until 2012.

AP Photo/Michael Graczyk[27]

Lethal injection’s continuing problems

From 1982 to 2010, 7% of all lethal injections were botched[28], making it the most error prone of America’s execution methods.

Since then difficulties[29] associated with lethal injection have multiplied.

They include[30] cases in which guards have had trouble finding a usable vein for an IV line, cases in which inmates have suddenly gasped for air or shown signs of consciousness long after the drugs started flowing, and others in which it took much longer than the expected time for the condemned person to die.

There have also been several badly botched lethal injections involving different drugs and protocols. Three of them occurred in 2014 alone.

Dennis McQuire gasped for air[31] for 25 minutes while the drugs Ohio used in his execution, hydromorphone and midazolam, slowly took effect.

Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma died of a heart attack[32] – not the drugs – 43 minutes after the start of his execution. Joseph Wood repeatedly gasped for one hour and 40 minutes[33] before his death was pronounced in Arizona.

In 2018 executioners in Alabama tried for two and a half hours[34] to find a vein, leaving Doyle Lee Hamm with 12 puncture marks, including six in his groin and others that punctured his bladder and penetrated his femoral artery, before his execution was called off.

Such deeply troubling failures have not[35] moved a majority on the current Supreme Court to recognize that they are constitutionally problematic. Yet they are evidence that lethal injection has not been the answer to America’s centurylong quest to find a method of execution that would be safe, reliable and humane.

References

- ^ Supreme Court has refused to hear four inmates’ challenge (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ expected to resume (deathpenaltyinfo.org)

- ^ federal moratorium on executions (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ alleged (www.wsj.com)

- ^ execution instructions (files.deathpenaltyinfo.org)

- ^ pentobarbital (pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ Federal Death Penalty Act (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ research on America’s methods of execution (www.sup.org)

- ^ looked at alternatives to hanging (www.popularmechanics.com)

- ^ Great Britain’s Royal Commission on Capital Punishment (scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu)

- ^ Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get expert takes on today’s news, every day. (theconversation.com)

- ^ anesthetic that would allow the condemned man (libcom.org)

- ^ Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ similar beliefs (www.history.com)

- ^ to adopt lethal injection (content.time.com)

- ^ claimed (papers.ssrn.com)

- ^ never been medically or scientifically studied on human beings (ir.lawnet.fordham.edu)

- ^ 37 states (www.hup.harvard.edu)

- ^ emerged (scholarship.law.upenn.edu)

- ^ pressured companies to stop making those drugs (papers.ssrn.com)

- ^ Glossip v. Gross (www.supremecourt.gov)

- ^ have gone their own ways (www.themarshallproject.org)

- ^ reports (deathpenaltyinfo.org)

- ^ fentanyl, a powerful opioid (theconversation.com)

- ^ nitrogen hypoxia (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ Tennessee’s electric chair (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ AP Photo/Michael Graczyk (www.apimages.com)

- ^ botched (www.sup.org)

- ^ difficulties (www.npr.org)

- ^ include (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ gasped for air (www.dispatch.com)

- ^ died of a heart attack (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ gasped for one hour and 40 minutes (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ tried for two and a half hours (theintercept.com)

- ^ have not (www.npr.org)

Authors: Austin Sarat, Associate Provost and Associate Dean of the Faculty and Cromwell Professor of Jurisprudence and Political Science, Amherst College