What the archaeological record reveals about epidemics throughout history – and the human response to them

- Written by Charlotte Roberts, Professor of Archaeology, Durham University

The previous pandemics to which people often compare COVID-19 – the influenza pandemic of 1918[1], the Black Death bubonic plague[2] (1342-1353), the Justinian plague[3] (541-542) – don’t seem that long ago to archaeologists. We’re used to thinking about people who lived many centuries or even millennia ago. Evidence found directly on skeletons shows that infectious diseases have been with us since our beginnings as a species.

Bioarchaeologists[4] like[5] us analyze skeletons to reveal more about how infectious diseases originated and spread in ancient times.

How did aspects of early people’s social behavior allow diseases to flourish? How did people try to care for the sick? How did individuals and entire societies modify behaviors to protect themselves and others?

Knowing these things[6] might help scientists understand why COVID-19 has wreaked such global devastation and what needs to be put in place before the next pandemic.

These round lesions are pathognomonic signs of syphilis.

Charlotte Roberts, CC BY-ND[7]

These round lesions are pathognomonic signs of syphilis.

Charlotte Roberts, CC BY-ND[7]

Clues about illnesses long ago

How can bioarchaeologists possibly know these things, especially for early cultures that left no written record? Even in literate societies, poorer and marginalized segments[8] were rarely written about.

In most archaeological settings, all that remains of our ancestors is the skeleton.

Tuberculosis leaves telltale markings in the spine.

Charlotte Roberts, CC BY-ND[9]

Tuberculosis leaves telltale markings in the spine.

Charlotte Roberts, CC BY-ND[9]

For some infectious diseases, like syphilis[10], tuberculosis[11] and leprosy[12], the location, characteristics and distribution of marks on a skeleton’s bones can serve as distinctive “pathognomonic[13]” indicators of the infection.

Most skeletal signs of disease are non-specific, though, meaning bioarchaeologists today can tell an individual was sick, but not with what disease. Some diseases never affect the skeleton at all, including plague and viral infections like HIV and COVID-19. And diseases that kill quickly don’t have enough time to leave a mark on victims’ bones.

To uncover evidence of specific diseases beyond obvious bone changes, bioarchaeologists use a variety of methods, often with the help of other specialists, like geneticists or parasitologists. For instance, analyzing soil collected in a grave from around a person’s pelvis can reveal the remains of intestinal parasites[14], such as tapeworms and round worms. Genetic analyses can also identify the DNA of infectious pathogens[15] still clinging to ancient bones and teeth.

Bioarchaeologists can also estimate age at death based on how developed a youngster’s teeth and bones are, or how much an adult’s skeleton has degenerated over its lifespan. Then demographers help us draw age profiles for populations that died in epidemics. Most infectious diseases disproportionately affect those with the weakest immune systems, usually the very young and very old.

For instance, the Black Death was indiscriminate; 14th-century burial pits[16] contain the typical age distributions found in cemeteries we know were not for Black Death victims. In contrast, the 1918 flu pandemic was unusual in that it hit hardest those with the most robust immune systems[17], that is, healthy young adults. COVID-19 today is also leaving a recognizable profile of those most likely to die from the disease, targeting older and vulnerable people[18] and particular ethnic groups[19].

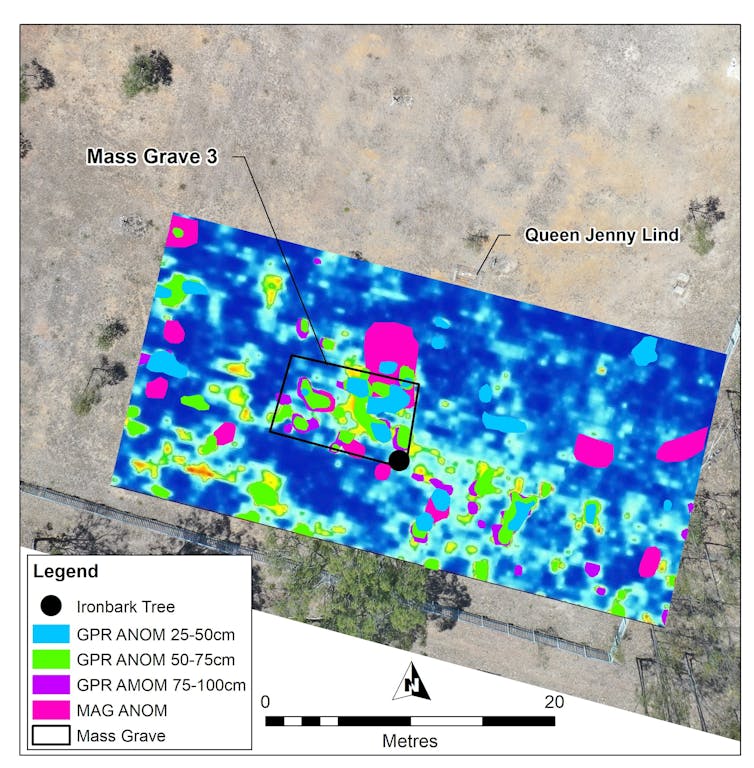

Ground penetrating radar shows mass graves from the small Aboriginal settlement of Cherbourg in Australia, where 490 out of 500 people were struck down by the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, with about 90 deaths.

Kelsey Lowe, CC BY-ND[20]

Ground penetrating radar shows mass graves from the small Aboriginal settlement of Cherbourg in Australia, where 490 out of 500 people were struck down by the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, with about 90 deaths.

Kelsey Lowe, CC BY-ND[20]

We can find out what infections were around in the past through our ancestors’ remains, but what does this tell us about the bigger picture of the origin and evolution of infections? Archaeological clues can help researchers reconstruct aspects of socioeconomic organization, environment and technology. And we can study how variations in these risk factors caused diseases to vary across time, in different areas of the world and even among people living in the same societies.

How infectious disease got its first foothold

Human biology affects culture in complex ways. Culture influences biology, too, although it can be hard for our bodies to keep up with rapid cultural changes. For example, in the 20th century, highly processed fast food replaced a more balanced and healthy diet for many. Because the human body evolved and was designed for a different world[21], this dietary switch resulted in a rise in diseases like diabetes, heart disease and obesity.

From a paleoepidemiological perspective, the most significant event in our species’ history was the adoption of farming. Agriculture arose independently[22] in several places around the world beginning around 12,000 years ago.

Prior to this change, people lived as hunter-gatherers, with dogs as their only animal companions[23]. They were very active and had a well balanced, varied diet that was high in protein and fiber and low in calories and fat. These small groups experienced parasites[24], bacterial infections[25] and injuries[26] while hunting wild animals and occasionally fighting with one another. They also had to deal with dental problems[27], including extreme wear, plaque and periodontal disease.

A healed fracture of the lower leg bones from a person buried in Roman Winchester, England.

Charlotte Roberts, CC BY-ND[28]

A healed fracture of the lower leg bones from a person buried in Roman Winchester, England.

Charlotte Roberts, CC BY-ND[28]

One thing hunter-gatherers didn’t need to worry much about, however, was virulent infectious diseases that could move quickly from person to person throughout a large geographic region. Pathogens like the influenza virus were not able to effectively spread or even be maintained by small, mobile, and socially isolated populations.

The advent of agriculture resulted in larger, sedentary populations of people living in close proximity. New diseases could flourish in this new environment. The transition to agriculture was characterized by high childhood mortality[29], in which approximately 30% or more of children died before the age of 5.

And for the first time in an evolutionary history spanning millions of years, different species of mammals and birds became intimate neighbors. Once people began to live with newly domesticated animals, they were brought into the life cycle of a new group of diseases – called zoonoses[30] – that previously had been limited to wild animals but could now jump into human beings.

Add to all this the stresses of poor sanitation and a deficient diet, as well as increased connections between distant communities through migration and trade especially between urban communities, and epidemics of infectious disease[31] were able to take hold for the first time.

Globalization of disease

Later events in human history also resulted in major epidemiological transitions related to disease.

For more than 10,000 years, the people of Europe, the Middle East and Asia evolved along with particular zoonoses in their local environments. The animals people were in contact with varied from place to place. As people lived alongside particular animal species over long periods of time, a symbiosis could develop – as well as immune resistance to local zoonoses.

At the beginning of modern history, people from European empires also began traveling across the globe, taking with them a suite of “Old World” diseases that were devastating for groups who hadn’t evolved alongside them. Indigenous populations in Australia[32], the Pacific[33] and the Americas[34] had no biological familiarity with these new pathogens. Without immunity, one epidemic after another ravaged these groups. Mortality estimates range between 60-90%.

This skull of a person who lived more than 2,600 years ago in Peru shows evidence of a surgery, maybe to treat a head wound.

This skull of a person who lived more than 2,600 years ago in Peru shows evidence of a surgery, maybe to treat a head wound.

The study of disease in skeletons, mummies and other remains of past people has played a critical role in reconstructing the origin and evolution of pandemics, but this work also provides evidence of compassion and care[35], including medical interventions such as trepanation[36], dentistry[37], amputation and prostheses[38], herbal remedies[39] and surgical instruments[40].

Other evidence shows that people have often done their best to protect others, as well as themselves, from disease. Perhaps one of the most famous examples is the English village of Eyam[41], which made a self-sacrificing decision to isolate itself to prevent further spread of a plague from London in 1665.

A tuberculosis sanatorium in São Paulo, Brazil, in the late 1800s.

Wellcome Collection, CC BY[42][43]

A tuberculosis sanatorium in São Paulo, Brazil, in the late 1800s.

Wellcome Collection, CC BY[42][43]

In other eras, people with tuberculosis were placed in sanatoria, people with leprosy were admitted to specialized hospitals or segregated on islands or into remote areas, and urban dwellers fled cities when plagues came.

As the world faces yet another pandemic, the archaeological and historical record are reminders that people have lived with infectious disease for millennia. Pathogens have helped shape civilization, and humans have been resilient in the face of such crises.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[44].]

References

- ^ influenza pandemic of 1918 (theconversation.com)

- ^ Black Death bubonic plague (theconversation.com)

- ^ Justinian plague (www.newyorker.com)

- ^ Bioarchaeologists (scholar.google.com)

- ^ like (scholar.google.com)

- ^ Knowing these things (doi.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ poorer and marginalized segments (southburnett.com.au)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ syphilis (www.dur.ac.uk)

- ^ tuberculosis (www.dur.ac.uk)

- ^ leprosy (www.dur.ac.uk)

- ^ pathognomonic (www.medicinenet.com)

- ^ intestinal parasites (doi.org)

- ^ DNA of infectious pathogens (www.dur.ac.uk)

- ^ 14th-century burial pits (www.americanscientist.org)

- ^ hit hardest those with the most robust immune systems (doi.org)

- ^ older and vulnerable people (www.bloomberg.com)

- ^ particular ethnic groups (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ designed for a different world (global.oup.com)

- ^ Agriculture arose independently (www.khanacademy.org)

- ^ dogs as their only animal companions (doi.org)

- ^ parasites (doi.org)

- ^ bacterial infections (doi.org)

- ^ injuries (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ dental problems (doi.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ high childhood mortality (doi.org)

- ^ zoonoses (www.who.int)

- ^ epidemics of infectious disease (boydellandbrewer.com)

- ^ Australia (australianstogether.org.au)

- ^ the Pacific (doi.org)

- ^ the Americas (www.sciencemag.org)

- ^ compassion and care (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ trepanation (thereader.mitpress.mit.edu)

- ^ dentistry (www.discovermagazine.com)

- ^ amputation and prostheses (theconversation.com)

- ^ herbal remedies (www.history.com)

- ^ surgical instruments (www.forbes.com)

- ^ English village of Eyam (www.bbc.com)

- ^ Wellcome Collection (wellcomecollection.org)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Charlotte Roberts, Professor of Archaeology, Durham University