Your guide to the 2020 census questionnaire

- Written by Aviva Rutkin, Data Editor

So, you’ve likely received your census questionnaire in the mail by now. But you might be wondering: Why these questions? Who came up with this list?

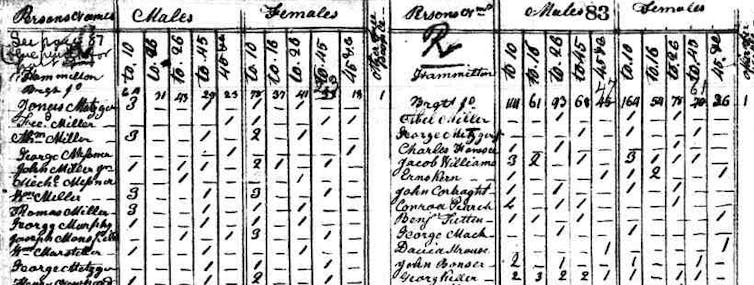

The questionnaire has changed a lot over time. In the first census[1], in 1790, U.S. marshals posed just a handful of questions to each head of household: their name; the number of free white males under and over 16; the number of free white females; the number of other free persons; and the number of slaves.

Emily Klancher Merchant, CC BY-SA[2]

Since then, the census has added and removed questions, as well as changed around the format[3] – for example, by giving some households longer, more detailed questionnaires, or by splitting questions into separate forms.

I called up Emily Klancher Merchant, a historian of science and technology at the University of California at Davis, and asked her to walk us through the 2020 questionnaire.

How many people were living or staying in this house, apartment, or mobile home on April 1, 2020?

Were there any additional people staying here on April 1, 2020 that you did not include in Question 1?

Traditionally, the census was done door to door. So an enumerator, also known as a census taker, would go door to door and ask how many people lived there. It wasn’t until 1850 that they started writing down the name of everyone who lived there.

This first question checks that the number of people who are going to be listed individually, later in the form, adds up to the number of people who are listed here. That second question is just to make sure that you’ve got everyone – like babies who were recently born, or grandparents or other relatives who might be staying with you.

For example, I have three people living in my house. When I’m writing down the name of each person, this question helps me to remember that I got everyone. But it’s also for the Census Bureau. If they notice that there are only two people listed, they go back and can try to find that missing person.

Emily Klancher Merchant, CC BY-SA[2]

Since then, the census has added and removed questions, as well as changed around the format[3] – for example, by giving some households longer, more detailed questionnaires, or by splitting questions into separate forms.

I called up Emily Klancher Merchant, a historian of science and technology at the University of California at Davis, and asked her to walk us through the 2020 questionnaire.

How many people were living or staying in this house, apartment, or mobile home on April 1, 2020?

Were there any additional people staying here on April 1, 2020 that you did not include in Question 1?

Traditionally, the census was done door to door. So an enumerator, also known as a census taker, would go door to door and ask how many people lived there. It wasn’t until 1850 that they started writing down the name of everyone who lived there.

This first question checks that the number of people who are going to be listed individually, later in the form, adds up to the number of people who are listed here. That second question is just to make sure that you’ve got everyone – like babies who were recently born, or grandparents or other relatives who might be staying with you.

For example, I have three people living in my house. When I’m writing down the name of each person, this question helps me to remember that I got everyone. But it’s also for the Census Bureau. If they notice that there are only two people listed, they go back and can try to find that missing person.

Early census schedules, like this one from 1810, were printed by hand.

U.S. Census Bureau[4]

Is this house, apartment, or mobile home… Owned by you or someone in this household with a mortgage or loan? Rented? Occupied without payment of rent?

This is something that’s been asked for a long time. I think it’s partly that the government is trying to get information about homeownership. The government can only ask questions on the census that it uses for administering policies.

What is your telephone number?

If there’s a discrepancy, or if there’s a question that you haven’t answered, they would call you to find out.

Please provide information for each person living here. If there is someone living here who pays the rent or owns this residence, start by listing him or her as Person 1. If the owner or the person who pays the rent does not live here, start by listing any adult living here as Person 1.

What is Person 1’s name?

What is Person 1’s sex?

What is Person 1’s age and what is Person 1’s date of birth?

There’s a really interesting story behind “Person 1.”

Originally, a census taker would go door to door and list everyone on the same list. For each household they would list the “head of household” first. Each person would be listed with their relationship to the head of the household – the wife of the head, child, parent.

There was no technical definition of a head of household. This wasn’t a category that was used for any formal purposes. But if there was a man in the household, the head would always be a man. A married woman could not be put as the head of household. If a married woman was, it would actually be changed at the Census Bureau.

In the 1970s, a small group of female demographers started protesting[5] this head-of-household designation. They started a working group to figure out, is this head-of-household designation really necessary? Is there some other, nonsexist way we can organize people in a household?

After that, the census used the concept of householder. So Person 1 could be anybody who owns the house or has their name on the lease.

Early census schedules, like this one from 1810, were printed by hand.

U.S. Census Bureau[4]

Is this house, apartment, or mobile home… Owned by you or someone in this household with a mortgage or loan? Rented? Occupied without payment of rent?

This is something that’s been asked for a long time. I think it’s partly that the government is trying to get information about homeownership. The government can only ask questions on the census that it uses for administering policies.

What is your telephone number?

If there’s a discrepancy, or if there’s a question that you haven’t answered, they would call you to find out.

Please provide information for each person living here. If there is someone living here who pays the rent or owns this residence, start by listing him or her as Person 1. If the owner or the person who pays the rent does not live here, start by listing any adult living here as Person 1.

What is Person 1’s name?

What is Person 1’s sex?

What is Person 1’s age and what is Person 1’s date of birth?

There’s a really interesting story behind “Person 1.”

Originally, a census taker would go door to door and list everyone on the same list. For each household they would list the “head of household” first. Each person would be listed with their relationship to the head of the household – the wife of the head, child, parent.

There was no technical definition of a head of household. This wasn’t a category that was used for any formal purposes. But if there was a man in the household, the head would always be a man. A married woman could not be put as the head of household. If a married woman was, it would actually be changed at the Census Bureau.

In the 1970s, a small group of female demographers started protesting[5] this head-of-household designation. They started a working group to figure out, is this head-of-household designation really necessary? Is there some other, nonsexist way we can organize people in a household?

After that, the census used the concept of householder. So Person 1 could be anybody who owns the house or has their name on the lease.

Female clerks tabulate census returns in 1901.

The Print Collector/Getty Images

Is Person 1 of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin?

What is Person 1’s race?

The census has always counted people by race. In the 1790 census, there were three categories: white, black and Indian.

Over time, the categories changed. They changed as the popular understanding of race changed and as the demographics of the U.S. population changed.

In the 19th century, there was a lot of anxiety about mixed-race people, so the census was starting to try to keep track of race mixing. You see the census adopting categories using really offensive terms like “mulatto” and “quadroon.” That ended up being really difficult for the census to keep track of – for obvious reasons, and also because at the time, an enumerator was going door to door and just assuming, rather than asking, about your family tree.

As the U.S. started getting more immigration from Asia, the bureau started adding categories to describe that. Some of them were national terms: Japanese, Chinese, Korean. There was also a Hindu category, meant to refer to people from South Asia.

In 1930, the census adopted a Mexican category[6], in part because a lot of members of Congress were concerned about immigration[7]. There was a lot of protest, particularly from the League of United Latin American Citizens and the Mexican government. It became a diplomatic issue. In 1940, the Census Bureau got rid of the Mexican category and it explicitly gave instructions to enumerators that people from Mexico are to be counted as white.

Then in 1977, the federal government adopted a standard set of racial categories[8] that were to be used for all federal statistical purposes. That set out four race categories: white, African American, Native American and Alaskan Native, and Asian and Pacific Islander. It also designated two ethnicity categories: Hispanic and not Hispanic. The purpose of these categories was specifically to enforce civil rights legislation, so the government could identify discrimination where it’s happening and address it.

The categories were revised in 1995, when Asian and Pacific Islander were separated. And, with the 2000 census, people started to be allowed to choose more than one race.

This is why we have these two separate questions. But this has become a problem for the Census Bureau, because it’s not the same way that people understand their own race or ethnicity. A lot of people just think about this as one category. And there is no real scientific definition of race or ethnicity, or the distinction between the two.

So people would answer one question and not the other, because they assumed these questions were asking the same thing. So the Census Bureau has done some work to understand what’s the best way to ask these two questions.

Print name of Person 2.

Does this person usually live or stay somewhere else?

This question is trying to make sure that they’re counting people only once. For example, a parent might list their college-aged child, but their child usually lives in a dorm in another city or state.

Female clerks tabulate census returns in 1901.

The Print Collector/Getty Images

Is Person 1 of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin?

What is Person 1’s race?

The census has always counted people by race. In the 1790 census, there were three categories: white, black and Indian.

Over time, the categories changed. They changed as the popular understanding of race changed and as the demographics of the U.S. population changed.

In the 19th century, there was a lot of anxiety about mixed-race people, so the census was starting to try to keep track of race mixing. You see the census adopting categories using really offensive terms like “mulatto” and “quadroon.” That ended up being really difficult for the census to keep track of – for obvious reasons, and also because at the time, an enumerator was going door to door and just assuming, rather than asking, about your family tree.

As the U.S. started getting more immigration from Asia, the bureau started adding categories to describe that. Some of them were national terms: Japanese, Chinese, Korean. There was also a Hindu category, meant to refer to people from South Asia.

In 1930, the census adopted a Mexican category[6], in part because a lot of members of Congress were concerned about immigration[7]. There was a lot of protest, particularly from the League of United Latin American Citizens and the Mexican government. It became a diplomatic issue. In 1940, the Census Bureau got rid of the Mexican category and it explicitly gave instructions to enumerators that people from Mexico are to be counted as white.

Then in 1977, the federal government adopted a standard set of racial categories[8] that were to be used for all federal statistical purposes. That set out four race categories: white, African American, Native American and Alaskan Native, and Asian and Pacific Islander. It also designated two ethnicity categories: Hispanic and not Hispanic. The purpose of these categories was specifically to enforce civil rights legislation, so the government could identify discrimination where it’s happening and address it.

The categories were revised in 1995, when Asian and Pacific Islander were separated. And, with the 2000 census, people started to be allowed to choose more than one race.

This is why we have these two separate questions. But this has become a problem for the Census Bureau, because it’s not the same way that people understand their own race or ethnicity. A lot of people just think about this as one category. And there is no real scientific definition of race or ethnicity, or the distinction between the two.

So people would answer one question and not the other, because they assumed these questions were asking the same thing. So the Census Bureau has done some work to understand what’s the best way to ask these two questions.

Print name of Person 2.

Does this person usually live or stay somewhere else?

This question is trying to make sure that they’re counting people only once. For example, a parent might list their college-aged child, but their child usually lives in a dorm in another city or state.

Man seated, taking U. S. Census, and four members of the Winnebago tribe standing, 1911.

Hocking Brothers/Buyenlarge/Getty Images

How is this person related to Person 1?

You can actually use this question to figure out most of the relationships within a household.

This year, for the first time, the census will offer the option of “same-sex husband/wife/spouse.”

It used to be spouse or other options like roommate or friend. But, the census had some issues figuring out couples who were living together but not married, especially starting in the 1970s.

The 1990 census was when we started seeing people of the same sex reporting as married to each other on a large scale. At the time, when that happened, the Census Bureau assumed that somebody’s sex got misreported. This assumption was actually true more often than one might think. Sex misreporting isn’t common, but because of the sheer number of opposite sex couples in the country, there were about as many sex-misreported couples as actual same-sex married couples back in 1990.

By the time the 2000 census happened, we had the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). According to DOMA, the federal government could not recognize same-sex marriage. So, when a same-sex couple would identify themselves as married, the bureau would change their relationship status to unmarried. That created a ton of statistical problems[9]. A nontrivial number of opposite-sex married couples misreported somebody ‘s sex and got transformed by the Census Bureau into an unmarried same-sex couple, which made data about same-sex couples and their families unreliable.

This is why the Census Bureau now specifically asks opposite-sex spouse or same-sex spouse. It’s hard to know what you’re dealing with otherwise.

Want to learn more about the 2020 census? This is an excerpt from our new email course, which will send informative emails straight to your inbox for three weeks. Sign up here to learn more about how the census affects your community[10].

Man seated, taking U. S. Census, and four members of the Winnebago tribe standing, 1911.

Hocking Brothers/Buyenlarge/Getty Images

How is this person related to Person 1?

You can actually use this question to figure out most of the relationships within a household.

This year, for the first time, the census will offer the option of “same-sex husband/wife/spouse.”

It used to be spouse or other options like roommate or friend. But, the census had some issues figuring out couples who were living together but not married, especially starting in the 1970s.

The 1990 census was when we started seeing people of the same sex reporting as married to each other on a large scale. At the time, when that happened, the Census Bureau assumed that somebody’s sex got misreported. This assumption was actually true more often than one might think. Sex misreporting isn’t common, but because of the sheer number of opposite sex couples in the country, there were about as many sex-misreported couples as actual same-sex married couples back in 1990.

By the time the 2000 census happened, we had the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). According to DOMA, the federal government could not recognize same-sex marriage. So, when a same-sex couple would identify themselves as married, the bureau would change their relationship status to unmarried. That created a ton of statistical problems[9]. A nontrivial number of opposite-sex married couples misreported somebody ‘s sex and got transformed by the Census Bureau into an unmarried same-sex couple, which made data about same-sex couples and their families unreliable.

This is why the Census Bureau now specifically asks opposite-sex spouse or same-sex spouse. It’s hard to know what you’re dealing with otherwise.

Want to learn more about the 2020 census? This is an excerpt from our new email course, which will send informative emails straight to your inbox for three weeks. Sign up here to learn more about how the census affects your community[10].

References

- ^ the first census (www.census.gov)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ changed around the format (www.census.gov)

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau (www.census.gov)

- ^ a small group of female demographers started protesting (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ adopted a Mexican category (muse.jhu.edu)

- ^ were concerned about immigration (theconversation.com)

- ^ adopted a standard set of racial categories (wonder.cdc.gov)

- ^ created a ton of statistical problems (escholarship.org)

- ^ Sign up here to learn more about how the census affects your community (theconversation.com)

Authors: Aviva Rutkin, Data Editor

Read more https://theconversation.com/your-guide-to-the-2020-census-questionnaire-136113