Checking blood for coronavirus antibodies – 3 questions answered about serological tests and immunity

- Written by Aubree Gordon, Professor of Public Health, University of Michigan

Coronavirus testing in the United States is moving into a new phase as scientists begin looking into people’s blood for signs they’ve been infected by SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. This technique is called serological testing.

Virologist Daniel Stadlbauer[1] helped develop a serological test to detect SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and helped transfer it from the research lab to the clinical setting. Epidemiologist Aubree Gordon[2] regularly uses serological assays in her research studies on influenza and dengue fever. She’s now established serological testing for SARS-CoV-2 in her research lab.

Here, the collaborators explain how the technology works.

What do these tests look for?

Serological tests for SARS-CoV-2 are blood tests. They look at serum or plasma – basically blood that has been processed to remove the cells – for evidence that at some point you’ve been infected with the coronavirus.

These tests look for antibodies that your body’s immune system generated to fight the infection. So, the tests detect the response to the virus, not the virus itself. They cannot be used early in infection, before a patient’s body has mounted an antibody response.

A serological test may focus on different types of antibodies. It can measure what are called neutralizing antibodies[3], which protect against the virus in question. Or it may measure what are called binding antibodies, a type that recognizes SARS-CoV-2 but does not necessarily protect against it.

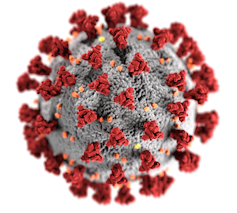

An illustration of one SARS-CoV-2 virus particle shows its spike proteins (in red) scattered across its surface.

CDC/ Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAMS, CC BY[4][5]

An illustration of one SARS-CoV-2 virus particle shows its spike proteins (in red) scattered across its surface.

CDC/ Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAMS, CC BY[4][5]

Several types of serological tests for SARS-CoV-2 exist. Clinical laboratories and research laboratories typically use what’s called an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that consists of plastic plates[6] that are coated with lab-made proteins that match those on the surface of the virus. For the test to be specific, it uses the spike protein from the surface of SARS-CoV-2 that gives the coronavirus its crown-like appearance.

This spike protein is immunogenic, meaning it’s one of the main targets of the body’s immune response; an infected person would make antibodies against the spike protein. The test measures if and how many[7] serum antibodies in the sample bind to the viral proteins on the plates.

Another type of serological test uses what’s called a lateral flow assay. A variety of medical tests, including at-home pregnancy tests, use this technique. It relies on liquid flowing over a pad treated with chemicals that will interact with the molecule you are testing for. Usually the test will indicate the presence or absence of antibodies through easy-to-read lines. They have the benefit of being relatively simple and rapid, but are generally less sensitive and do not give a measure of the amount of antibody present. The FDA has so far approved one test of this type, from the company Cellex[8].

Why is it helpful to know who has antibodies against the virus?

From a public health perspective, knowing who has already been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 paints a clearer picture of how widespread the virus is in the local population.

Some people are asymptomatic or only came down with mild symptoms[9], so they might not be counted in other COVID-19 statistics. Epidemiologists can use the serology results to determine how common those cases are. Serological studies can also help figure out a death rate for COVID-19, by clarifying how many people in total have been sick.

Serosurveys are currently generating[10] this kind of data. They use the serological techniques to test a large number of serum samples from people without a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, coming up with statistics about the group as a whole.

Knowing a true rate of infection allows public health workers to better predict the likely future course of the pandemic in individual locations and figure out what interventions are needed to control an outbreak. That’s because researchers think[11], although no one’s entirely sure yet[12], that once you have antibodies to the virus it will confer immunity, meaning you’ll be protected for some period of time.

A nurse has blood drawn to check whether she has antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, and hopefully immunity.

SEBASTIEN BOZON/AFP via Getty Images[13]

A nurse has blood drawn to check whether she has antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, and hopefully immunity.

SEBASTIEN BOZON/AFP via Getty Images[13]

Serological testing could also be used to make strategic staffing decisions about essential workers, including medical personnel – for instance, assigning to the front lines those who are have antibodies and are thus presumably immune. These people would be able to go back to work without the risk of getting sick or infecting others.

Identifying individuals who were already infected and who are now potentially immune could play an important part in when and how social distancing restrictions are lifted. Broad SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing could help control the pandemic until a potent vaccine is available – the real coronavirus “end game.”

Where are these tests being performed so far?

Serological testing is already being used to identify people who can serve as plasma donors.

In a process called plasmapheresis, doctors transfer plasma that contains antibodies to a disease into an ill person. Plasmapheresis has been used for decades[14] to treat a variety of diseases.

In this case, plasma from someone who has recovered from COVID-19 – or was infected with the disease but didn’t develop symptoms and has a high level of antibodies – is transferred into a sick patient, typically someone critically ill. At Mount Sinai hospital in New York City[15], medical workers have started transferring plasma into patients with the hope of neutralizing the virus and alleviating the disease. In other locations, hospitals have started[16] or are preparing to begin this process as well.

Serological testing is also being used to diagnose individual patients who are suspected SARS-CoV-2 cases, but have not tested positive for the virus using the molecular test that looks for the virus’s genetic material.

Multiple serosurveys are underway, or soon will be, in medical systems and in the general population. For instance, Beaumont Hospital System in Michigan has begun a large serosurvey in their medical staff[17]. The Krammer[18] and Simon[19] research labs at Mount Sinai have started a serosurvey with samples from New York City.

No self-administered finger prick tests have yet been approved by the FDA.

Christopher Furlong/Getty Images News via Getty Images[20]

No self-administered finger prick tests have yet been approved by the FDA.

Christopher Furlong/Getty Images News via Getty Images[20]

Commercial companies have also developed serological tests, including many rapid tests, that are making their way into the marketplace. Ultimately these may be very useful for letting individuals know their infection status. But the currently available commercial tests haven’t been validated by the FDA[21] or a similar authority to say they work well.

There is such high, unmet demand that for the most part, clinical laboratories are choosing to put together their own serological tests, using publicly available instructions, something which is common in research laboratories, but not done as often in U.S. clinical laboratories. Though it takes more time and effort than purchasing ready-to-go tests, which are hard to come by anyway, it provides the clinical labs access to serological tests that have been proven to work well.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter[22].]

References

- ^ Virologist Daniel Stadlbauer (scholar.google.com)

- ^ Epidemiologist Aubree Gordon (scholar.google.com)

- ^ neutralizing antibodies (www.virology.ws)

- ^ CDC/ Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAMS (phil.cdc.gov)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ plastic plates (www.virology.ws)

- ^ test measures if and how many (doi.org)

- ^ from the company Cellex (www.fda.gov)

- ^ asymptomatic or only came down with mild symptoms (www.npr.org)

- ^ Serosurveys are currently generating (www.nih.gov)

- ^ because researchers think (doi.org)

- ^ no one’s entirely sure yet (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ SEBASTIEN BOZON/AFP via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ Plasmapheresis has been used for decades (theconversation.com)

- ^ At Mount Sinai hospital in New York City (health.mountsinai.org)

- ^ In other locations, hospitals have started (hub.jhu.edu)

- ^ begun a large serosurvey in their medical staff (www.clevescene.com)

- ^ Krammer (labs.icahn.mssm.edu)

- ^ Simon (labs.icahn.mssm.edu)

- ^ Christopher Furlong/Getty Images News via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ haven’t been validated by the FDA (www.fda.gov)

- ^ Read The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Aubree Gordon, Professor of Public Health, University of Michigan