Balloon releases have deadly consequences – we're helping citizen scientists map them

- Written by Lara O'Brien, Master's Degree Candidate in Conservation Ecology and Environmental Informatics, University of Michigan

Balloons are often seen as fun, harmless decorations. But they become deadly litter as soon as they are released into the air and forgotten.

Plastic pollution is one of today’s biggest environmental challenges. Microplastics have been found in our drinking water[1], food[2] and even the air we breathe[3]. While many people are trying to reduce their use of single-use plastic bags, bottles, utensils and straws, balloons are often overlooked.

To help bring attention to the environmental dangers of released balloons, one of us (Lara O’Brien) created a citizen science survey to track and map balloon debris. This work is designed to raise awareness about the dangers of balloons, while also gathering data to help influence policies regulating celebratory balloon releases.

Balloons cause many kinds of damage

Deliberate releases of tens, hundreds or sometimes thousands of balloons are common sights at weddings, graduations, memorials, sporting events[4] and other celebrations. These fleeting feel-good acts inflict long-lasting and potentially deadly consequences on the environment and wildlife.

Balloons filled with helium – a finite and rapidly dwindling resource[5] – travel hundreds[6] or even thousands of miles[7]. They land as litter on beaches, rivers, lakes, oceans, forests and other natural areas.

The two most common types of balloons are Mylar[8] and latex. Mylar balloons, also called foil balloons, are made from plastic nylon sheets with a metallic coating and will never biodegrade. They also cause thousands of power outages[9] every year when they come into contact with power lines or circuit breakers.

While some manufacturers claim that natural latex balloons made from liquid rubber are biodegradable, they still take years to break down[10] because they are mixed with plasticizers and other chemical additives that hinder the biodegradation process. Other latex balloons are synthetic[11], made from a petroleum derivative called neoprene – the same material used to make scuba diving wetsuits – and will remain in the environment indefinitely, breaking down into smaller and smaller pieces over time.

Both Mylar and latex balloons are a significant threat to wildlife[12], livestock[13] and pets, which can be injured or killed from eating balloon fragments, getting tangled in long balloon ribbons or strings, or being spooked by the falling debris.

More than 100 balloons collected at the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge in New Jersey.

USFWS/Flickr, CC BY[14][15]

More than 100 balloons collected at the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge in New Jersey.

USFWS/Flickr, CC BY[14][15]

Latex shreds: A deadly meal

Unlike Mylar balloons, latex balloons burst in the atmosphere, shredding into small pieces that, when floating on the surface of water, resemble jellyfish[16] or squid. Plastic debris in the ocean can also become coated with algae and other marine microbes that produce a chemical scent, which sea turtles[17], seabirds[18], fish[19] and other marine life associate with food. Because they are soft and malleable, latex balloons easily conform to an animal’s stomach cavity or digestive tract and can cause obstruction, starvation and death.

As a result, latex balloons are the deadliest form of marine debris for seabirds[20]. They are 32 times more likely to kill than hard plastics when ingested. Balloons tied with ribbons and strings also rank just behind discarded fishing gear and plastic bags and utensils[21] due to the high risk of entanglement and death that they pose to marine life.

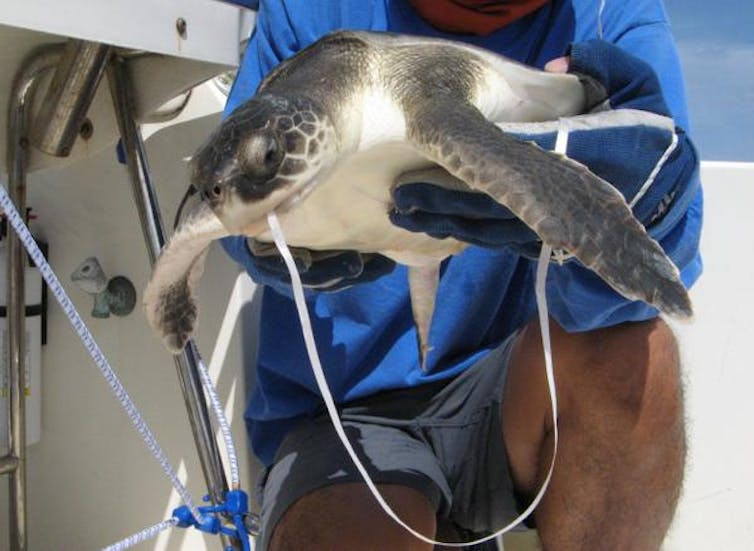

This juvenile Kemps Ridley sea turtle has ingested balloon debris.

Blair Witherington, Florida FWC/NOAA, CC BY[22][23]

This juvenile Kemps Ridley sea turtle has ingested balloon debris.

Blair Witherington, Florida FWC/NOAA, CC BY[22][23]

Volunteers track debris in real time

Environmental organizations are working to both clean up and record data on plastic pollution and marine debris, including balloons. Between 2016 and 2018, volunteers with the Alliance for the Great Lakes[24] picked up and recorded more than 18,000 pieces of balloon debris[25]. In 2019 the International Coastal Cleanup[26], an annual event organized by the Ocean Conservancy[27], recorded over 104,150 balloons[28] found around the world, with almost half in the United States.

Utilizing citizen science[29] as a way to collect more data and help raise awareness in the Great Lakes region and beyond, Lara O'Brien created an online survey[30] in June 2019 that people can use to record the date, location, condition and photo of balloon debris. The survey is completely anonymous and can be easily accessed on a smartphone, so users can document balloon debris they find while walking the dog, hiking or participating in a beach cleanup.

Since the survey began, citizen scientists have helped record more than 1,580 pieces of balloon debris found in an area stretching from remote Isle Royale National Park[31] in Lake Superior to Sandbanks Provincial Park[32] in Lake Ontario. Surveys and photos[33] have also been submitted from Washington state, Oregon, Montana, Nevada, Kansas, Florida, Iceland and the United Kingdom.

Interactive map of balloon debris sightings submitted since June 2019. Zoom in and click/tap on individual points for more information, including photo attachments. Source: Balloondebris.org[34].

The most important feature of this survey allows volunteers to pinpoint and submit the exact GPS coordinates of balloon debris in real time. This geospatial data is immediately uploaded onto an interactive map[35] that clearly and powerfully shows where released balloons end up, and how prevalent and widespread balloon waste is. It helps researchers see emerging patterns or trends that might be present, including potential hotspots[36] where higher concentrations of balloon debris may occur.

In the United States, balloons float eastward with prevailing west-to-east winds. In the Great Lakes region, higher concentrations of balloon debris have been reported along the eastern shores of Lakes Michigan and Huron. This includes the Indiana Dunes National Park[37] southeast of Chicago, where volunteers regularly come across balloons. One person reported finding 84 balloons in a single morning along a two-mile stretch of beach.

Interactive heat map showing where the greatest concentrations of balloon debris in the Great Lakes region have been found since June 2019. Source: Balloondebris.org[38].

Ending balloon pollution

Thanks to research like this and work by organizations such as Balloons Blow[39], the Alliance for the Great Lakes[40] and the NOAA Marine Debris Program[41], awareness of balloon pollution is growing. More people are choosing to use alternatives and urging schools[42], businesses and other organizations to stop balloon releases.

A growing movement across the United States is calling for more policies and laws restricting or eliminating single-use plastics, including balloons. California, Connecticut, Florida, Tennessee and Virginia have all passed laws prohibiting the deliberate release of balloons in order to protect the environment and wildlife. Others, including Maryland[43], Kentucky[44] and Arizona[45], are considering similar bans.

Volunteers who want to collect data and map the location of balloon debris in their communities may visit the project’s page[46] on the citizen science site SciStarter or at balloondebris.org[47]. There they can find links to the survey, interactive maps, photos, suggestions for eco-friendly alternatives and more. By helping people visualize and understand balloon pollution, we hope to prevent future balloon releases.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter[48].]

References

- ^ drinking water (orbmedia.org)

- ^ food (graphics.reuters.com)

- ^ the air we breathe (www.vice.com)

- ^ sporting events (cbs4indy.com)

- ^ a finite and rapidly dwindling resource (www.bbc.com)

- ^ hundreds (www.mlive.com)

- ^ thousands of miles (www.dailymail.co.uk)

- ^ Mylar (www.tekra.com)

- ^ thousands of power outages (www.dailynews.com)

- ^ take years to break down (www.indystar.com)

- ^ synthetic (www.industrialoutpost.com)

- ^ wildlife (www.wideopenspaces.com)

- ^ livestock (www.king5.com)

- ^ USFWS/Flickr (flic.kr)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ jellyfish (rubberjellyfishmovie.com)

- ^ sea turtles (www.cell.com)

- ^ seabirds (advances.sciencemag.org)

- ^ fish (royalsocietypublishing.org)

- ^ deadliest form of marine debris for seabirds (doi.org)

- ^ discarded fishing gear and plastic bags and utensils (oceanconservancy.org)

- ^ Blair Witherington, Florida FWC/NOAA (blog.marinedebris.noaa.gov)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Alliance for the Great Lakes (greatlakes.org)

- ^ 18,000 pieces of balloon debris (www.freep.com)

- ^ International Coastal Cleanup (oceanconservancy.org)

- ^ Ocean Conservancy (oceanconservancy.org)

- ^ over 104,150 balloons (www.coastalcleanupdata.org)

- ^ citizen science (dx.doi.org)

- ^ online survey (balloondebris.weebly.com)

- ^ Isle Royale National Park (www.nps.gov)

- ^ Sandbanks Provincial Park (www.ontarioparks.com)

- ^ photos (balloondebris.weebly.com)

- ^ Balloondebris.org (balloondebris.weebly.com)

- ^ an interactive map (balloondebris.weebly.com)

- ^ potential hotspots (balloondebris.weebly.com)

- ^ Indiana Dunes National Park (www.nps.gov)

- ^ Balloondebris.org (balloondebris.weebly.com)

- ^ Balloons Blow (balloonsblow.org)

- ^ Alliance for the Great Lakes (greatlakes.org)

- ^ NOAA Marine Debris Program (marinedebris.noaa.gov)

- ^ schools (www.easthamptonstar.com)

- ^ Maryland (www.wusa9.com)

- ^ Kentucky (www.kfvs12.com)

- ^ Arizona (www.abc15.com)

- ^ project’s page (scistarter.org)

- ^ balloondebris.org (balloondebris.weebly.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Lara O'Brien, Master's Degree Candidate in Conservation Ecology and Environmental Informatics, University of Michigan