Segregation policies in federal government in early 20th century harmed Blacks for decades

- Written by Guo Xu, Assistant Professor of Business and Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley

Economic disparities in earnings, health and wealth between Black and white Americans are staggeringly large[1]. Historical government practices and institutions – such as segregated schools[2], redlined neighborhoods[3] and discrimination in medical care[4] – have contributed to these wide disparities. While these causes may not always be overt, they can have lasting negative effects on the prosperity of minority communities.

Abhay Aneja[5] and I are researchers at University of California, Berkeley, who specialize in examining the causes of social inequality. Our new research[6] examines the U.S. federal government’s role in creating conditions of racial inequality more than a century ago. Specifically, we researched the harmful impact of government discrimination against Black civil service employees. We also examined how such discrimination continues to affect their families decades later, rippling across future generations.

Decades of discrimination

Soon after his inauguration in 1913, President Woodrow Wilson ushered in one of the most far-reaching discrimination policies of that century. Wilson discreetly authorized his Cabinet secretaries to implement a policy of racial segregation[7] across the federal bureaucracy.

A Southerner by heritage, Wilson appointed several Southern Democrats to Cabinet offices, several of whom were sympathetic to the segregationist cause. Wilson’s new postmaster general, for example, was “anxious to segregate white and negro employees in all Departments of Government[8].” Historical accounts suggest that Wilson’s order was carried out most aggressively by the U.S. Postal Service and the U.S. Treasury Department, the latter responsible for revenue generation including taxes and customs duties[9]. Based on the data we collected, the majority of Black civilians worked in these two federal departments before Wilson’s arrival.

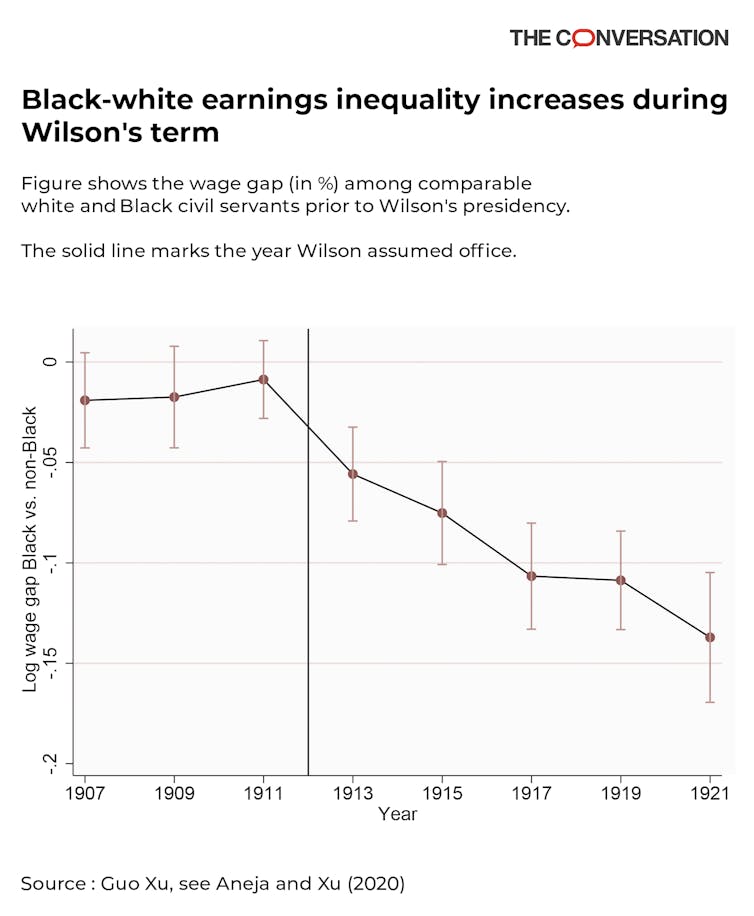

Segregation as federal policy widens income disparity for Black Americans.

Figure by Aneja and Xu (2020), CC BY-ND[10][11]

Segregation as federal policy widens income disparity for Black Americans.

Figure by Aneja and Xu (2020), CC BY-ND[10][11]

Given his support among Southern Democrats, one goal of the Wilson administration was to limit the access of Black civil servants to the highest positions within government. This outcome was achieved through both demotions and reductions, efforts to discourage the hiring of qualified Black candidates.

For example, photos became required[12] to apply for government jobs in order to screen out Black candidates. Black Americans already employed in the federal civil service were transferred from relatively high-status posts to low-paying ones[13]. This overall policy of Jim Crow-style segregation served to shut out Black Americans from working in one of the few places where they could find opportunities for economic mobility and success.

Deep roots of economic disparities

Despite the potential for enormous harm, the cost of segregation to the economic status of Black civil servants has long remained unknown. Our research started by examining how President Wilson contributed to earnings disparities between Black and white civil service workers. In so doing, our research added to the collective knowledge within the social sciences about the roots of racial inequality.

To build a database on earnings inequality, our team undertook a large-scale data digitization of previously undigitized and, to our knowledge, unexamined historical government records containing a detailed list of all people who worked for the federal government and what they earned each year. These records were contained in eight volumes of the Official Register of the U.S., a series spanning 1907 to 1921. For 1907, we obtained information for 125,000 workers. By 1921, the size of the government workforce had more than doubled.

Segregation as commonplace as a drink of water.

kickstand/E+ via Getty Images[14]

Segregation as commonplace as a drink of water.

kickstand/E+ via Getty Images[14]

This data collection and cleaning process created a comprehensive dataset[15] to understand the operation of the American federal government at the beginning of the 20th century. It not only described a worker’s position and salary, but also contained rich personal information including a federal employee’s place of birth, the state from which they were appointed and the Cabinet department where they worked.

Because the register was issued every two years, our research made it possible to track a civil servant’s career progression over time. Looking at this data source, it was clear that President Wilson’s policy of segregating the federal workforce exacted an enormous cost from Black civil servants.

Sidelining Black federal workers

To isolate the impact of racial discrimination and establish comparable jobs and salaries, the analysis paired Black and white federal employees with similar characteristics. Each worked in the same city, the same government office and even had the same salary before President Wilson’s inauguration. Within this set of comparable workers, Black civil servants earned about 7% less than their white counterparts during Wilson’s two terms as president.

When we account for differences in civil servants, such as educational background, the reduction in earnings suffered by Black civil servants remains. Moreover, under the order to segregate, Black civil servants were less likely to be promoted over time and more likely to be demoted. This disparate treatment by the federal government enabled white civil servants to earn more over time than Black civil servants with the same levels of skill and experience. Our research[16] provides strong evidence for the discriminatory nature of workplace segregation faced by Black Americans within the federal government.

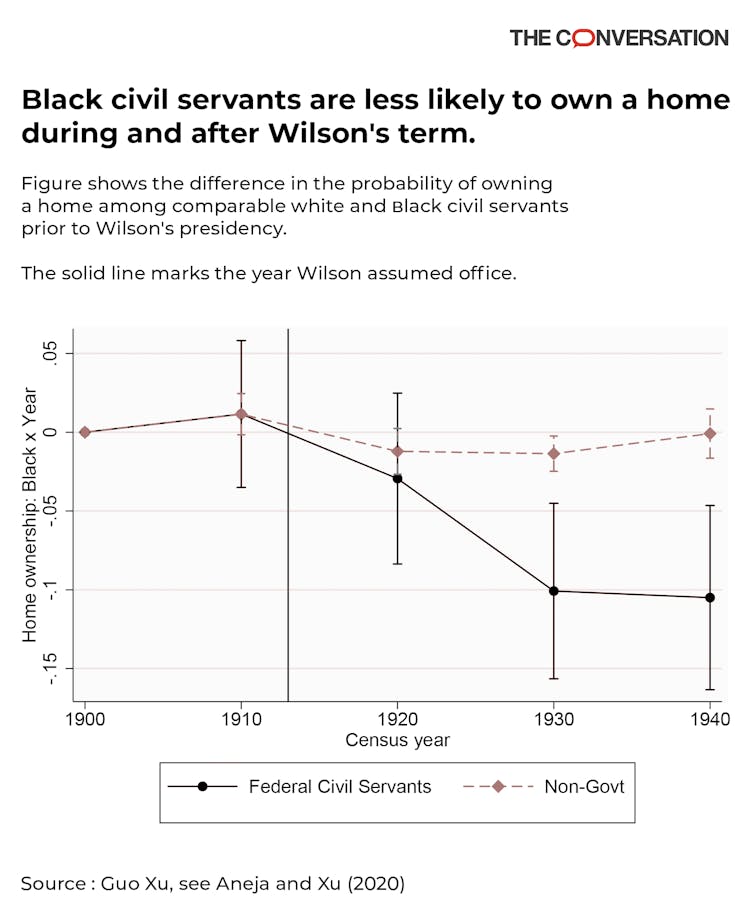

Black workers targeted by federal policies earned less money and had less capacity to own a home.

Figure by Aneja and Xu (2020), CC BY-NC-ND[17][18]

Black workers targeted by federal policies earned less money and had less capacity to own a home.

Figure by Aneja and Xu (2020), CC BY-NC-ND[17][18]

Our research shows that the damage caused by working under discriminatory conditions persisted well beyond Wilson’s presidency. The same Black civil servants victimized by discrimination in federal employment were also less likely to own a home in 1920, 1930 and 1940, almost three decades after Wilson was elected. Moreover, the school-age children of Black civil servants who served in the Wilson administration went on to have poorer-quality lives than their young white counterparts in terms of their overall earnings and quality of employment in adulthood.

This research can help to contribute to the understanding of the roots of economic disparities. A policy of racial discrimination – even if implemented temporarily – has lasting negative effects. A clearer understanding of historical discrimination can help to inform the design of policies aimed at remedying the painfully persistent racial inequities we observe today.

References

- ^ staggeringly large (bfi.uchicago.edu)

- ^ segregated schools (www.journals.uchicago.edu)

- ^ redlined neighborhoods (www.chicagofed.org)

- ^ medical care (www.nber.org)

- ^ Abhay Aneja (scholar.google.com)

- ^ new research (www.nber.org)

- ^ implement a policy of racial segregation (uncpress.org)

- ^ anxious to segregate white and negro employees in all Departments of Government (books.google.com)

- ^ taxes and customs duties (doi.org)

- ^ Figure by Aneja and Xu (2020) (www.nber.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ photos became required (www.pbs.org)

- ^ high-status posts to low-paying ones (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ kickstand/E+ via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ comprehensive dataset (www.nber.org)

- ^ research (www.nber.org)

- ^ Figure by Aneja and Xu (2020) (www.nber.org)

- ^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)

Authors: Guo Xu, Assistant Professor of Business and Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley