As climate change erodes US coastlines, an invasive plant could become an ally

- Written by Judith Weis, Professor Emerita of Biological Sciences, Rutgers University Newark

Many invasive species are found along U.S. coasts, including fishes, crabs, mollusks and marsh grasses. Since the general opinion is that invasives are harmful, land managers and communities spend a lot of time and resources attempting to remove them. Often this happens before much is known about their actual effects, either good or bad.

The common reed Phragmites australis is a tall perennial grass with long leaves that invades fresh and brackish wetlands. There it crowds out native species, reducing plant diversity. Managers frequently kill it with herbicides and replace it in brackish marshes with native Spartina alterniflora, or cordgrass, during restoration projects.

But despite its bad reputation, Phragmites provides many benefits that are generally unknown and unappreciated. After studying salt marsh ecology[1] and the impacts of stressors, including invasive plants, for many years, I have concluded that removing this invasive species wherever it is found – especially along vulnerable coastlines – is a very expensive and often foolish procedure.

Providing food and shelter

Phragmites actually is native in the United States[2], but the native form comprises only a minor component of the high marsh – the zone that typically is above water. A new genetic variety arrived many decades ago[3] and invaded brackish marshes.

In Europe and Asia, where Phragmites is also native, it is valued as an important wetland species. In China, where Spartina alterniflora has arrived, marsh scientists and managers are concerned with the effects of that invader replacing their beloved Phragmites[4]. Human attitudes toward invasive species can be a bit subjective.

An Ohio field overgrow with invasive Phragmites.

USGS[5]

An Ohio field overgrow with invasive Phragmites.

USGS[5]

In the 1990s, my research group reviewed the limited state of knowledge on how Phragmites invasions were affecting mid-Atlantic coastal areas. We found a few studies indicating that fish[6] and invertebrates[7] in tidal creeks of Phragmites marshes in New England and the Mid-Atlantic[8] were roughly as abundant[9] and diverse as those in Spartina marshes. In other words, we did not find a major negative impact from Phragmites invasions.

We also did some behavioral laboratory studies examining relationships of estuarine animals to Phragmites (reeds) and Spartina (cordgrass). These investigations showed that grass shrimp, fiddler crabs and killifish chose both plants equally, and that both plants gave grass shrimp comparable protection against their predator, killifish[10].

To check these results in the field, we did studies at a tidal creek with cordgrass on one side and reeds on the other[11]. Here we again found comparable numbers of animals in the mud on both sides of the creek.

Findings can vary in different locations. Some researchers have found that fish assemblages are similar in both marshes, while others have shown them to be less dense in Phragmites. Some studies found that killifish were clearly reduced in Phragmites marshes[12].

Marsh plants also provide food for many animals after they die and decay, producing detritus that enters estuarine food webs. When we ground up decaying leaves from Phragmites and Spartina and fed it to fiddler crabs and grass shrimp, the two plants provided equivalent nutrition. Both plants supported survival and growth of fiddler crabs, but neither one supported shrimp survival beyond three weeks[13].

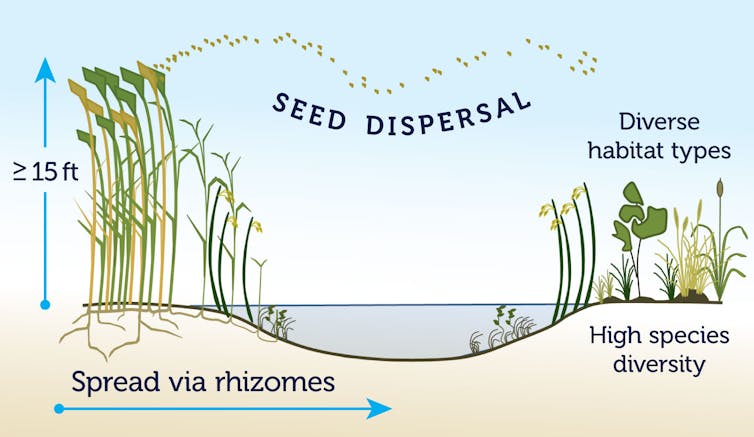

Phragmites can spread through aerial seed dispersal or via rhizomes (underground stems).

Great Lakes Phragmites Collaborative, CC BY-ND[14][15]

Phragmites can spread through aerial seed dispersal or via rhizomes (underground stems).

Great Lakes Phragmites Collaborative, CC BY-ND[14][15]

Habitat for terrestrial animals and plants

Marshes are habitat for many kinds of birds, both year-round and during migration. Phragmites supports many birds and other land animals, though not as many as Spartina.

Studies comparing the density of individuals or the numbers of species in reeds versus other plants show variable results[16]. Extensive, dense beds of tall reeds seem to support fewer species of breeding birds than do smaller beds, sparse stands and stands of reeds mixed with other plants.

In some cases, Phragmites appears to benefit roosting birds, songbirds eating seeds during migration or winter, animals taking refuge from flooding in high reed stands and small mammals like cottontails that hide in reed patches[17]. It appears to harm other species: For example, it shades turtle nesting sites and displaces other plant species[18] in the high salt marsh.

Absorbing pollutants and buffering shorelines

Over the past several decades many studies have shown that marshes help clean the environment by filtering water and removing pollutants. Spartina and Phragmites absorb comparable amounts of metal pollutants from sediments into their roots, but Spartina sends more of those toxic materials into its stems and leaves, from which the metals are excreted back into the ecosystem. Phragmites keeps more pollutants in its roots, sequestering them from the rest of the ecosystem[19].

Phragmites also is better at sequestering other pollutants of concern, including nitrogen[20] and carbon dioxide[21]. By absorbing excess nitrogen from water, Phragmites helps reduce algal blooms and the formation of low-oxygen “dead zones.” And by taking up more carbon dioxide, it reduces carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, slowing climate change.

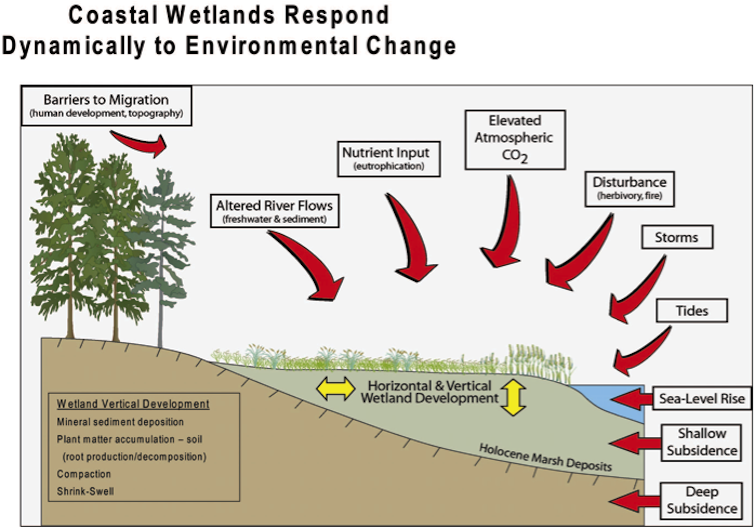

Tidal marshes in New England and the mid-Atlantic are very vulnerable to sea level rise[22]. Many are not increasing their elevation fast enough to keep up, and risk being submerged unless they can elevate faster or move inland. And when steep slopes, houses or roads are located landward of a marsh, it can’t migrate inland.

Coastal wetlands are threatened by sea level rise, but accumulation of plant matter can help offset this process.

Cahoon et al via USGS, CC BY-ND[23][24]

Coastal wetlands are threatened by sea level rise, but accumulation of plant matter can help offset this process.

Cahoon et al via USGS, CC BY-ND[23][24]

Phragmites creates more detritus when it dies and traps more sediments, thus enabling marshes to elevate more rapidly than Spartina[25]. It builds and stabilizes marsh soils, which store carbon; it also protects tidal marshes from erosion associated with sea level rise. At a time when marshes are seriously threatened by climate change, this function is particularly important.

Some people dislike reeds because they grow tall and dense and block homeowners’ views of the water. However, during storms, taller and denser plants provide better protection than shorter, sparser ones.

A useful invader

Twenty years ago, marsh biologists J.E. Rooth and J.C. Stevenson observed that Phragmites “may provide resource managers with a strategy of combating sea-level rise, and current control measures fail to take this into consideration[26].” This observation is still true.

Phragmites supports many animals, although somewhat fewer than Spartina, and performs other valuable services. In view of current concerns about sea level rise and marsh survival, I believe killing it everywhere is impractical and expensive, hurts sensitive species and wastes resources.

In my view, the preferred approach should shift away from trying to eradicate Phragmites wherever it appears. A better approach would emphasize modifying stands of it to create habitat for particular species while maintaining its other valuable functions.

References

- ^ studying salt marsh ecology (runewarkbiology.rutgers.edu)

- ^ native in the United States (www.fws.gov)

- ^ arrived many decades ago (doi.org)

- ^ replacing their beloved Phragmites (doi.org)

- ^ USGS (www.usgs.gov)

- ^ fish (doi.org)

- ^ invertebrates (dx.doi.org)

- ^ Mid-Atlantic (dx.doi.org)

- ^ abundant (doi.org)

- ^ comparable protection against their predator, killifish (doi.org)

- ^ cordgrass on one side and reeds on the other (www.urbanhabitats.org)

- ^ reduced in Phragmites marshes (doi.org)

- ^ neither one supported shrimp survival beyond three weeks (doi.org)

- ^ Great Lakes Phragmites Collaborative (www.greatlakesphragmites.net)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ variable results (doi.org)

- ^ hide in reed patches (doi.org)

- ^ displaces other plant species (doi.org)

- ^ sequestering them from the rest of the ecosystem (doi.org)

- ^ nitrogen (doi.org)

- ^ carbon dioxide (doi.org)

- ^ very vulnerable to sea level rise (dx.doi.org)

- ^ Cahoon et al via USGS (woodshole.er.usgs.gov)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ more rapidly than Spartina (doi.org)

- ^ fail to take this into consideration (doi.org)

Authors: Judith Weis, Professor Emerita of Biological Sciences, Rutgers University Newark