Virginia politics: The uneasy marriage of new liberalism and historic racism

- Written by Julian Maxwell Hayter, Associate Professor of Leadership Studies, University of Richmond

Virginia is home to America’s original contradiction – the peculiar juxtaposition of slavery and freedom[1].

The recent “blue-ing” of Virginia has obscured a sobering political reality: Racial progress and racial bigotry can exist at the same time.

Those contradictions were on display when Democratic Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam recently admitted to, and subsequently denied, being photographed in blackface in the early 1980s[2].

Northam is the latest elected official to fan the flames of America’s tortured racial history.

The Eastern Virginia Medical School yearbook photo shows a man in blackface standing next to a person in Ku Klux Klan[3] attire. This image, nearly three decades old, ignited a chain of nationwide commentary on the current state of American race relations.

The photo represents another sobering reminder of old bigotry in contemporary politics.

And while racist political power is not specific to Virginia, the “Old Dominion” is, and has been, a bellwether for American politics – the good and the bad, but mostly the contradictory.

As a historian of 20th-century American history and Richmond, Virginia’s recent political history[4], these contradictions have contemporary connotations.

Reconciliation and dehumanization

Despite its recent history of voting Democratic, ambivalent political traditions continue to characterize the Commonwealth. The home of the Confederacy’s capital, Richmond, also gave the United States its first African-American governor in 1990, Lawrence Douglas Wilder[5].

Virginia also helped elect[6] Barack Obama, twice[7].

Virginians voted for Barack Obama in both 2008 and 2012. Here, he’s campaigning in 2018 for Democratic candidates.

AP/Jacquelyn Martin[8]

Virginians voted for Barack Obama in both 2008 and 2012. Here, he’s campaigning in 2018 for Democratic candidates.

AP/Jacquelyn Martin[8]

But in the late 19th century, Southerners and Virginians met the challenges of slavery’s abolition with legal and social racial separation. This separation, commonly referred to as Jim Crow segregation[9], was not only sanctioned by state laws, many of these laws lasted until the late 1960s.

In other words, Southern black Americans were not full citizens of the United States until the 1960s and Jim Crow mitigated many African-Americans’ upwardly mobile aspirations.

Northam, who campaigned on racial reconciliation yet allegedly once wore a costume inextricably linked to black dehumanization, embodies this American dilemma – a dilemma with deeply segregationist overtones.

That Virginia, the wealthiest state of the former Confederacy, has recently turned blue is a watershed moment in American political development.

When the Commonwealth went for Obama in the 2008 presidential election, Virginians ended nearly four decades of conservative control over Southern presidential politics. Virginia also cast all its 13 electoral votes for Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Much of this is attributable[10] to the growth and diversifying of populations in Northern Virginia near Washington, D.C., the Hampton Roads region and the Richmond metropolitan area.

Virginia’s recent elections undeniably helped shatter the Southern Strategy[11], a long-term Republican plan designed to break Democrats’ dominance over Southern politics. A region that has trended red since the ratification of the Voting Rights Act of 1965[12] had turned blue.

But developments in national politics cannot alone explain Northam’s and Attorney General Mark Herring’s[13] ostensibly contradictory behavior. Herring – the state’s third-most powerful elected official – also recently admitted to donning blackface.

If blackface is inextricably linked to slavery, people wearing blackface in the 1980s is attributable to racial segregation. In understanding this crisis, Virginia’s history matters.

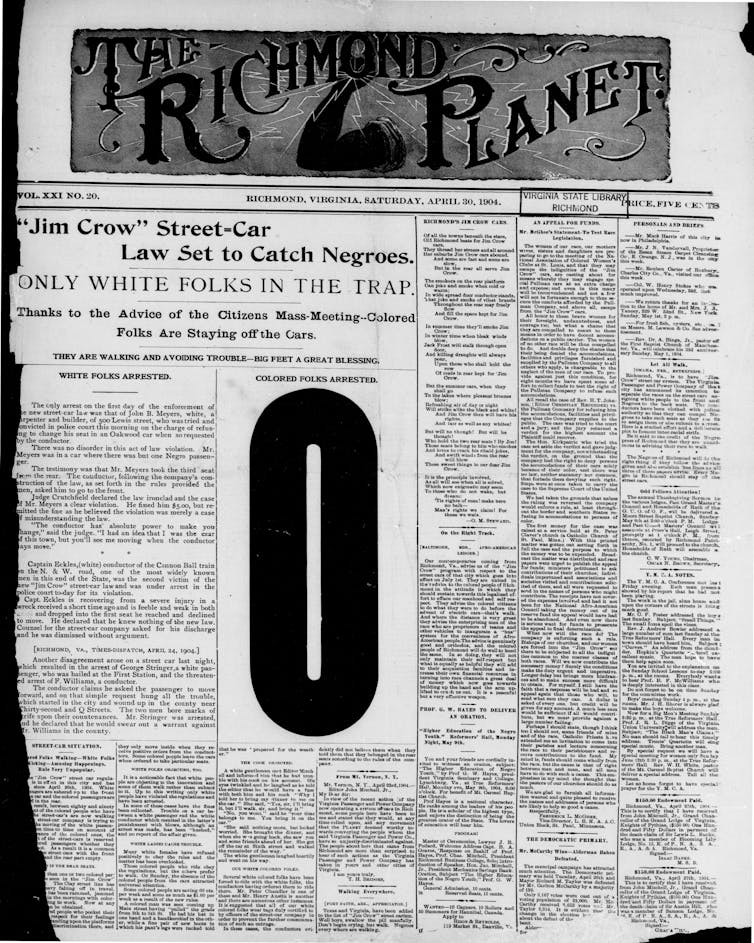

The April 30, 1904 Richmond Planet described a Jim Crow law meant to bar blacks from streetcars.

Library of Congress[14]

The April 30, 1904 Richmond Planet described a Jim Crow law meant to bar blacks from streetcars.

Library of Congress[14]

Segregation and the suburbs

Virginia’s 20th-century political history is nothing short of scandalous.

Poll taxes (a fee required to vote) determined who voted in the Commonwealth until 1966[15]. Virginia’s Constitutional Convention of 1901-02 eventually erased 80 percent of African-Americans and 50 percent of whites[16] from the polls. Throughout the early 20th century, the Commonwealth had the lowest voter turnout rate in America and one of the lowest rates of any free democracy in the world. By 1959, the year of Northam’s birth, these obstacles to democracy continued to shape politics in the Commonwealth.

The undemocratic face of disenfranchisement had grave implications for Northam’s generation.

In fact, disenfranchisement ensured that mid-20th century Virginians inherited an oligarchy – a small number of people controlled the political structure.

A handful of well-heeled segregationists used disenfranchisement to spearhead Southern “massive resistance”[17] to public school integration in 1956. Anxiety over integration gave rise to unprecedented white flight to suburbs – not just in Virginia, but throughout America.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the same officials used the power vested in the General Assembly to clear urban slums, build freeways – often through communities whose voters had been disenfranchised – and compress the descendants of former slaves into isolated public housing projects. While these urban policies shaped cities throughout the United States, Jim Crow laws and disenfranchisement expedited this process in Virginia (and throughout the South).

By 1970[18], Richmond’s poverty rate was 25 percent. African-Americans bore the brunt of that poverty.

The city’s public schools were nearly 80 percent African-American by 1980. In 1985, Richmond trailed only Detroit in murder rate per capita. Between 1970 and 1980 alone, approximately 40,000 whites – of roughly 140,000 in 1970 – fled to Richmond’s suburbs.

In other words, segregationists, along with federal officials, helped create the inner city and suburban growth at the same time.

Progress isn’t linear

Americans remember the story of the civil rights movement as a triumph of democracy. History speaks otherwise.

Many of Virginia’s cities were more segregated by race and class in 1980 than in 1960.

In time, segregation undermined the types of social trust – the notion that people can understand and count on one another[19] – that experts argue is required for thriving communities.

It also explains how students from racially homogeneous communities populated Virginia’s predominantly white colleges during the 1980s.

These were the colleges where students such as Northam wore blackface. The Virginia Military Institute, Northam’s alma mater, did not integrate until 1968[20]. That was only 13 years before Northam graduated from the institute in 1981.

These places were in short supply of racial diversity well into the late 20th century. They remind Americans that nowhere have white and black Americans been closer together, yet further apart, than beneath the Mason-Dixon line.

The new divide

More ominously, the politics of segregation outlived Jim Crow laws.

By the 1980s, white flight and congressional redistricting (namely, the compression of black voters into exclusively urban enclaves) hastened the rise of regional partisanship. And while this rise in partisanship characterized American politics broadly, it hit the South and Virginia hard – a region that Democrats dominated for nearly seven decades.

As African-Americans hitched their wagons to Democrats, many whites fled the Democratic Party. They left a party that was once home to generations of Southern racists who would never contemplate belonging to Abraham Lincoln’s GOP, and became Republicans.

Virginia’s policymakers drew district boundaries to protect these white areas from the voting power of urbanites, who were mostly black.

In time, residential segregation and redistricting gave rise to shockingly predictable electoral outcomes. Cities trended liberal, while rural and suburban areas mostly voted conservatively.

Between 1970 and 1988, only 13 African-Americans had served on Virginia’s General Assembly. Yet, African-Americans made up nearly 20 percent of Virginia’s population in the 1980s. The total number of African-Americans in the General Assembly did not exceed five until 1984.

To this day, a disproportionate number of the Commonwealth’s legislators are from rural and suburban enclaves.

Liberal in blackface

Governor Northam not only inherited this Virginia, he was a product of it.

Millennial voters[21] are relocating to once-predominantly African-American cities and the so-called “Great Inversion”[22] out of American suburbs continues.

The once “solid South” is up for grabs.

Political consultants[23] have long recognized and exploited these changes. In fact, these trends changed the political composition of not just Virginia, but America.

Yet old habits die hard.

The re-emergence of Confederate memorialization[24] and white supremacy[25] in Virginia is a panic reaction to these political and demographic developments.

Is it any wonder, then, that a son of the segregated Virginia might wear blackface in one era – yet recognize the political expediency of racial reconciliation in another?

References

- ^ the peculiar juxtaposition of slavery and freedom (books.wwnorton.com)

- ^ being photographed in blackface in the early 1980s (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ shows a man in blackface standing next to a person in Ku Klux Klan (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ Richmond, Virginia’s recent political history (www.kentuckypress.com)

- ^ Lawrence Douglas Wilder (www.encyclopediavirginia.org)

- ^ helped elect (www.usnews.com)

- ^ Barack Obama, twice (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ AP/Jacquelyn Martin (www.apimages.com)

- ^ Jim Crow segregation (www.pbs.org)

- ^ Much of this is attributable (www.dailyprogress.com)

- ^ helped shatter the Southern Strategy (prospect.org)

- ^ ratification of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (www.kentuckypress.com)

- ^ Mark Herring’s (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Library of Congress (chroniclingamerica.loc.gov)

- ^ until 1966 (www.oyez.org)

- ^ 80 percent of African-Americans and 50 percent of whites (www.upress.virginia.edu)

- ^ “massive resistance” (www.virginiahistory.org)

- ^ By 1970 (www.kentuckypress.com)

- ^ the notion that people can understand and count on one another (timeline.com)

- ^ did not integrate until 1968 (www.dailypress.com)

- ^ Millennial voters (prospect.org)

- ^ “Great Inversion” (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Political consultants (www.newyorker.com)

- ^ Confederate memorialization (nextcity.org)

- ^ white supremacy (www.ajc.com)

Authors: Julian Maxwell Hayter, Associate Professor of Leadership Studies, University of Richmond