Brazil's president rejects COVID-19 vaccine, undermining a century of progress toward universal inoculation

- Written by Pedro Cantisano, Assistant Professor of History, University of Nebraska Omaha

The world is eagerly awaiting the release of several COVID-19 vaccines[1], but Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro is not.

Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro.

Andressa Anholete/Getty Images[2]

Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro.

Andressa Anholete/Getty Images[2]

“I’m not going to take it. It’s my right,” he said in a Nov. 26 social media broadcast[3].

Bolsonaro, who came down with COVID-19 in July[4], has also criticized face masks. He and his more faithful supporters oppose any suggestion of mandatory coronavirus vaccinations[5].

Vaccine resistance has a long history in Brazil.

In November 1904, thousands of people in the city of Rio de Janeiro protested government-mandated smallpox vaccinations in a famous revolt[6] that nearly ended with a coup.

Making modern Brazil

The smallpox vaccine had arrived in Brazil almost a century earlier[7]. But the syringes were long, left skin pockmarked and could transmit other diseases such as syphilis.

Between 1898 and 1904, only 2% to 10% of Rio’s population was vaccinated yearly, according to historian Sidney Chalhoub[8]. In 1904, smallpox killed 0.4% of Rio residents – a higher percentage of the population than COVID-19’s victims in New York City this year[9].

But these were not the only reasons Brazil made vaccinations mandatory in 1904.

As part of a “modernization” plan to attract European immigration and foreign investment, President Rodrigues Alves was committed to eradicating epidemics – not just smallpox, but also yellow fever and the bubonic plague.

To rid Rio de Janeiro, then the nation’s capital, of sanitary hazards while opening space for Parisian-style avenues and buildings[10], hundreds of tenements were demolished between 1903 and 1909. Almost 40,000 people – mostly Afro-Brazilians but also poor Italian, Portuguese and Spanish immigrants – were evicted and removed from downtown Rio. Many were left homeless, forced to resettle on nearby hillsides or in distant rural areas.

Meanwhile, public health agents accompanied by armed police systematically disinfected homes with sulfur that destroyed furniture and other belongings – whether residents welcomed them or not.

Conspiracy and barricades

Politicians and military officers who opposed President Alves saw opportunity[11] in the outrage these health initiatives caused. They stoked discontent.

With the help of labor organizers and news editors, Alves’ opponents led a campaign against Brazil’s public health mandates throughout 1904. Newspapers reported on violent home disinfections and forced vaccinations. Senators and other public figures declared that mandatory vaccinations encroached on people’s homes and bodies.

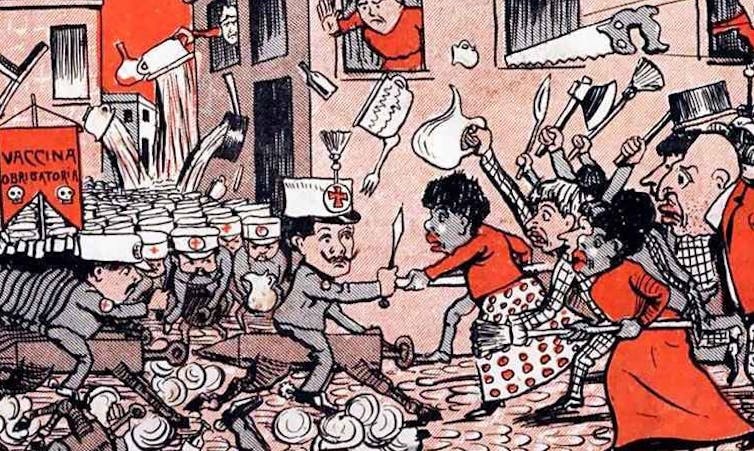

In mid-November of that year, thousands of protesters gathered in public squares to rally against public health efforts[12]. Rio police reacted with disproportionate force, triggering six days of unrest in the city. A racially diverse crowd of students, construction workers, port workers and other residents fought back, armed with rocks, housewares or the tools of their trade, flipping over streetcars to barricade the streets.

Brazil’s 1904 vaccine revolt pitted public health officials against the people of Rio de Janeiro.

O Malho magazine/Brazilian National Library’s Hemeroteca Digital[13]

Brazil’s 1904 vaccine revolt pitted public health officials against the people of Rio de Janeiro.

O Malho magazine/Brazilian National Library’s Hemeroteca Digital[13]

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, conspirators were mobilizing young military cadets. Their plan: to overthrow Alves’ government.

Their scheme was foiled when the president called upon both the Army and the Navy to contain protesters and detain alleged insurgents. Brazil’s great vaccine revolt was soon suppressed.

The language of rights

Afterward, newspapers portrayed protesters as an ignorant mass, manipulated by cunning politicians. They deemed one of the uprising’s popular leaders, Horácio José da Silva – known as “Black Silver” – a “disorderly thug.”

But Brazil’s vaccine revolt was more than a cynical political manipulation. Digging into archives, historians like me[14] are learning what really motivated the uprising.

The violent and segregationist features of Alves’ urban plan are one obvious answer[15]. In early 20th-century Brazil, most people – women, those who couldn’t read, the unemployed – couldn’t vote. For these Brazilians, the streets were the only place to have their voices heard.

But why would they so virulently oppose methods that controlled the spread of disease?

Delving into newspapers and legal records, I have found that critics of Brazil’s 1904 public health drive often expressed their opposition in terms of “inviolability of the home[16],” both on the streets and in courts.

For elite Brazilians, invoking this constitutional right was about protecting the privacy of their households, where men ruled over wives, children and servants. Public health agents threatened this patriarchal authority[17] by demanding access to homes and women’s bodies.

Poor men and women in Rio also held patriarchal values[18]. But for them there was more than privacy at stake in 1904.

Throughout the 19th century, enslaved Afro-Brazilians had formed families and built homes, even on plantations[19], carving out spaces of relative freedom from their masters. After slavery was abolished in 1888, many freed Afro-Brazilians shared crowded tenements with immigrants. By the time of Alves’s vaccination drive, the poor of Rio had been fighting eviction and police violence for decades.

For Black Brazilians, then, defending their rights to choose what to do – or not to do – with their homes and bodies was part of a much longer struggle for social, economic and political inclusion.

Deadly learning experience

Four years after the 1904 revolt, Rio was struck by another smallpox epidemic. With so many people unvaccinated, deaths doubled; almost 1% of the city perished.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[20].]

It was a deadly learning experience. From then on, Brazilian leaders framed mandatory smallpox, measles and other vaccines as a means to protect the common good, and invested in educational campaigns to explain why. Throughout the 20th century, vaccinations were extremely successful in Brazil[21]. Since the 1990s, 95% of children have been vaccinated, though the numbers are dropping[22].

The American epidemiologist Fred L. Soper giving yellow fever vaccinations in Belem, Brazil, in the 1930s.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images[23]

The American epidemiologist Fred L. Soper giving yellow fever vaccinations in Belem, Brazil, in the 1930s.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images[23]

Today, Brazil is one of the countries hardest hit[24] by the coronavirus pandemic. As in the past, Afro-Brazilians are hurting more than others[25].

By invoking Brazilians’ individual right not to get vaccinated against COVID-19, President Bolsonaro is ignoring the lessons of 1904 – undermining a century of hard work fighting disease in Brazil.

References

- ^ eagerly awaiting the release of several COVID-19 vaccines (www.bbc.com)

- ^ Andressa Anholete/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ he said in a Nov. 26 social media broadcast (www.reuters.com)

- ^ came down with COVID-19 in July (www.cnn.com)

- ^ oppose any suggestion of mandatory coronavirus vaccinations (politica.estadao.com.br)

- ^ famous revolt (library.brown.edu)

- ^ almost a century earlier (www.americasquarterly.org)

- ^ according to historian Sidney Chalhoub (www.companhiadasletras.com.br)

- ^ COVID-19’s victims in New York City this year (www1.nyc.gov)

- ^ Parisian-style avenues and buildings (www.jstor.org)

- ^ saw opportunity (www.cambridge.org)

- ^ gathered in public squares to rally against public health efforts (multirio.rio.rj.gov.br)

- ^ O Malho magazine/Brazilian National Library’s Hemeroteca Digital (multirio.rio.rj.gov.br)

- ^ historians like me (scholar.google.com)

- ^ one obvious answer (www.jstor.org)

- ^ inviolability of the home (www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br)

- ^ Public health agents threatened this patriarchal authority (utpress.utexas.edu)

- ^ also held patriarchal values (www.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ Afro-Brazilians had formed families and built homes, even on plantations (quod.lib.umich.edu)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ vaccinations were extremely successful in Brazil (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ though the numbers are dropping (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ is one of the countries hardest hit (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Afro-Brazilians are hurting more than others (theconversation.com)

Authors: Pedro Cantisano, Assistant Professor of History, University of Nebraska Omaha