Regime change means different things to different people. Either way, it hasn’t happened in Venezuela … yet

- Written by Andrew Latham, Professor of Political Science, Macalester College

The U.S. mission to seize Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro has pushed the concept of regime change back into everyday conversation. “Regime Change in America’s Back Yard,” declared The New Yorker[1] in a piece that typified the response to the Jan. 3 operation that saw Maduro exchange a compound in Caracas for a jail in Brooklyn.

Commentators[2] and politicians[3] have been using the term as shorthand for removing Maduro and ending Venezuela’s crisis, as if the two were essentially the same thing. But they are not.

In fact, to an international relations specialist like me[4], the use of “regime change” to explain what just went down in Venezuela muddies the term rather than clarifies it. I’ll explain.

Regime change, as it has been practiced and discussed in international politics, refers to something far more ambitious and far more consequential than plucking out a single leader. It is an attempt by an outside power to transform how another country is governed, not just change who governs it.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that regime change in Venezuela isn’t still in the cards. Only that Maduro being replaced by his deputy[5], former Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, doesn’t reach that bar yet – even if, as U.S. President Donald Trump has suggested, she will be under pressure to toe Washington’s line[6].

Understanding this distinction is essential to grasping what is at stake in Venezuela as it transitions to a post-Maduro world, but not necessarily one[7] removed from the Chavismo ideology that Maduro inherited from his predecessor, Hugo Chavez.

A more technical removal

Regime change[8], as it is understood by most foreign policy analysts, refers to efforts by external actors to force a deep transformation of another state’s system of rule. The aim is to reshape who holds authority and how power is exercised by changing the structure and institutions of political power, rather than a government’s policies or even its personnel.

Once understood this way, the history of the term comes into clearer view.

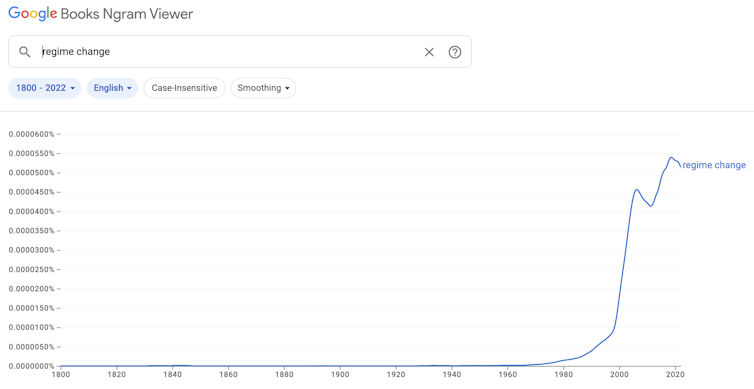

The concept of “regime change” gained wider use after the Cold War[9] as a way to describe externally imposed political transformation without relying on older, more direct terms.

Military and political leaders in earlier eras tended to speak openly of overthrow, deposition, invasion or interference in another state’s internal affairs.

In contrast, the newer term “regime change” sounded technical and restrained. It suggested planning and manageability rather than domination, softening the reality that what was being discussed was the deliberate dismantling of another country’s political order.

That choice of language mattered. Describing the overthrow of governments as “regime change” reduced the moral and legal weight associated with coercive intervention.

It also carried an assumption that political systems could be taken apart and rebuilt through expertise and design.

The term implied that once an existing order was removed, a more acceptable one would take its place, and that this transition could be guided from the outside.

And then came Iraq

During the 1990s and early 2000s, this assumption became embedded[10] in the thinking of the U.S. foreign policy establishment.

Regime change came to be associated with ambitious efforts to replace hostile governments with fundamentally different systems of rule. Iraq became the most important test of that idea[11].

The intervention by the U.S. in 2003 succeeded in removing Saddam Hussein’s government[12], but it also exposed the limits of externally driven transformation.

Along with Hussein, senior members of his long-ruling Ba'ath Party were banned from involvement in the new government – this was real regime change.

The collapse of the existing order in Iraq following the U.S.-led invasion, however, did not yield a stable successor. Instead, it produced a violent struggle for power[13] that outside powers were unable to control.

That experience altered how the term was understood. The term regime change did not disappear from political debate, but its meaning shifted. It became a label tied to concerns about overreach and the risks of assuming that foreign powers can reengineer political systems.

In this usage, regime change no longer promised control or resolution. It functioned as a warning drawn from experience.

A fine distinction

Both meanings are now visible in discussions of Venezuela. Some audiences invoke regime change[14] to signal resolve and a willingness to break an entrenched system that appears resistant to reform.

Others hear the same term and think of earlier cases[15] where the collapse of a regime produced fragmentation and prolonged instability. The significance attached to the concept depends on who is using it and what political purpose it serves.

This distinction matters because externally driven regime change does not end when a government falls or a dictator is removed. It sets off a contest over how power will be reorganized once existing institutions are dismantled.

This article is part of a series explaining foreign policy terms[16] commonly used but rarely explained.

References

- ^ declared The New Yorker (www.newyorker.com)

- ^ Commentators (www.cnn.com)

- ^ and politicians (www.aljazeera.com)

- ^ international relations specialist like me (www.macalester.edu)

- ^ replaced by his deputy (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ under pressure to toe Washington’s line (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ necessarily one (www.miamiherald.com)

- ^ Regime change (www.britannica.com)

- ^ gained wider use after the Cold War (origins.osu.edu)

- ^ became embedded (www.cambridge.org)

- ^ important test of that idea (www.cfr.org)

- ^ succeeded in removing Saddam Hussein’s government (www.aljazeera.com)

- ^ violent struggle for power (www.reuters.com)

- ^ invoke regime change (www.politico.com)

- ^ think of earlier cases (www.politico.com)

- ^ series explaining foreign policy terms (theconversation.com)

Authors: Andrew Latham, Professor of Political Science, Macalester College