What AI earbuds can’t replace: The value of learning another language

- Written by Gabriel Guillén, Professor of Language Studies, Middlebury College

Your host in Osaka, Japan, slips on a pair of headphones[1] and suddenly hears your words transformed into flawless Kansai Japanese. Even better, their reply in their native tongue comes through perfectly clear to you.

Thanks to artificial intelligence, neither of you is lost in translation. What once seemed like science fiction is now marketed as a quick fix[2] for cross-cultural communication.

Such AI-powered tools will be useful for many people, especially for tourists or in any purely transactional situation, even if seamless automatic interpretation remains at an experimental stage[3].

Does this mean the process of learning another language will soon be a thing of the past?

As scholars of computer-assisted language learning[4] and linguistics[5], we disagree and see language learning as vital in other ways. We have devoted our careers to this field because we deeply believe in the lasting and transformative value of learning and speaking languages beyond one’s mother tongue.

Lessons from past language ‘disruptions’

This isn’t the first time a new technology has promised massive disruption to learning languages.

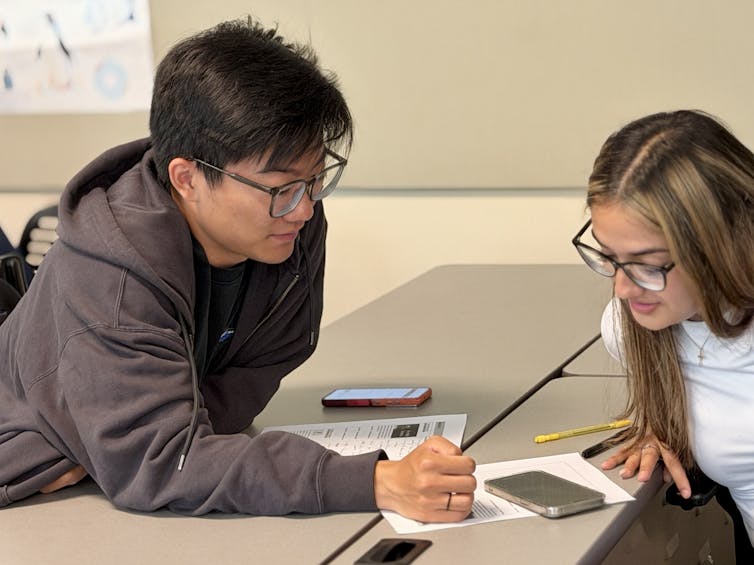

In recent years, language learning startups such as Duolingo aimed to make acquiring a language easier than ever, in part by gamifying language. While these apps have certainly made learning more accessible[6] to more people, our research shows[7] most platforms and apps have failed to fully replicate the inherently social process of learning a language.

One thing’s clear: The massive popularity of language apps shows there’s still strong demand for language learning[9], despite a sharp decline in formal education settings[10]. Duolingo alone had 113.1 million monthly active users[11] around the world at the end of 2024, a 36% increase over the prior year. This is about 10 times more than the number of students who take languages other than English in U.S. schools.

The meaning of learning a language

Numbers aside, the gold standard of language learning is the ability to follow and contribute to a live group conversation[12].

Since World War II, government departments and education programs recognized that text-centered grammar-translation[13] methods did little to support real interaction. Interpersonal conversational competence gradually became the main goal of language classes. While technologies you can put in your ear or wear on your face now promise to revolutionize interpersonal interaction, their usefulness in such conversations actually falls along a spectrum.

At one end, you have simple tasks you have to navigate while visiting a city where they speak a different language, like checking out of a hotel, buying a ticket at a kiosk or finding your way around town. That is, people from different backgrounds working together to achieve a goal – a successful checkout, a ticket purchase or getting to the famous museum you want to visit. Any mix of languages, gestures or tools[14] – even AI tools – can help in this context. In such cases, where the goal is clear and both parties are patient, shared English or automated interpretation can get the job done while bypassing the hard work of language learning.

At the other end, identity matters as much as content. Meeting your in-laws, introducing yourself at work, welcoming a delegation or presenting to a skeptical audience all involve trust and social capital. Humor, idioms, levels of formality, tone, timing and body language shape not just what you say but who you are.

The effort of learning a language communicates respect, trust and a willingness to see the world through someone else’s eyes. We believe language learning is one of the most demanding and rewarding forms of deep work, building cognitive resilience, empathy, identity and community in ways technology struggles to replicate.

The 2003 movie “Lost in Translation[15],” which depicts an older American man falling in love with a much younger American woman, was not about getting lost in the language but delved into issues of interculturality and finding yourself while exposed to the other.

Indeed, accelerating mobility[16] due to climate migration, remote work and retirement abroad all increase the need to learn languages – not just translate them. Even those staying in place often seek deeper connections through language as learners with familial and historical ties[17].

Where AI falls short

The latest AI technologies, such as those used by Apple’s newest AirPods[19] to instantly interpret and translate, certainly are powerful tools that will help a lot of people interact with anyone who speaks a different language in ways previously only possible for someone who spent a year or two studying it. It’s like having your own personal interpreter.

Yet relying on interpretation carries hidden costs[20]: distortion of meaning, loss of interactive nuance and diminished interpersonal trust.

An ethnography of American learners[21] with strong motivation and near limitless support found that falling back on speaking English and using technology to aid translation may be easier in the short term, but this undercuts long-term language and integration goals. Language learners constantly face this choice between short-term ease and long-term impact.

Some AI tools help accomplish immediate tasks, and generative AI apps can support acquisition[22] but can take away the negotiations of meaning[23] from which durable skills emerge.

AI interpretation may suffice for one-on-one conversations, but learners usually aspire[24] to join ongoing conversations already being had among speakers of another language. Long-term language learning, while necessarily friction-filled, is nevertheless beneficial on many fronts.

Interpersonally, using another’s language fosters both cultural[25] and cognitive[26] empathy.

In addition, the cognitive benefits of multilingualism are equally well documented: resistance[27] to dementia[28], divergent thinking[29], flexibility[30] in shifting attention[31], acceptance[32] of multiple perspectives and explanations[33], and reduced bias[34] in reasoning.

The very attributes companies seek[35] in the AI age – resilience, lifelong learning, analytical and creative thinking, active listening – are all cultivated through language learning.

Rethinking language education in the age of AI

So why, in the increasingly multilingual U.K.[36] and U.S., are fewer students choosing to learn another language in high school[37] and at university[38]?

The reasons are complex.

Too often, institutions have struggled to demonstrate the relevance[39] of language studies. Yet innovative approaches abound, from integrating language in the contexts of other subjects[40] and linking it to service and volunteering[41] to connecting students with others through virtual exchanges[42] or community partners via project-based language learning[43], all while developing intercultural skills[44].

So, again, what’s the value of learning another language when AI can handle tourism phrases, casual conversation and city navigation?

The answer, in our view, lies not in fleeting encounters but in cultivating enduring capacities: curiosity, empathy, deeper understanding of others, the reshaping of identity and the promise of lasting cognitive growth.

For educators, the call is clear. Generative AI can take on rote and transactional tasks while excelling at error correction, adapting input and vocabulary support. That frees classroom time for multiparty, culturally rich and nuanced conversation.

Teaching approaches grounded in interculturality, embodied communication, play and relationship building will thrive. Learning this way enables learners to critically evaluate what AI earbuds or chatbots create, to join authentic conversations and to experience the full benefits of long-term language learning.

References

- ^ pair of headphones (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ now marketed as a quick fix (www.bloomberg.com)

- ^ automatic interpretation remains at an experimental stage (www.atanet.org)

- ^ computer-assisted language learning (www.middlebury.edu)

- ^ linguistics (www.middlebury.edu)

- ^ made learning more accessible (doi.org)

- ^ our research shows (doi.org)

- ^ Jakub Porzycki/NurPhoto via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ for language learning (www.fortunebusinessinsights.com)

- ^ sharp decline in formal education settings (www.insidehighered.com)

- ^ 113.1 million monthly active users (investors.duolingo.com)

- ^ contribute to a live group conversation (doi.org)

- ^ text-centered grammar-translation (catalog.hathitrust.org)

- ^ languages, gestures or tools (www.taylorfrancis.com)

- ^ Lost in Translation (www.imdb.com)

- ^ accelerating mobility (www.migrationpolicy.org)

- ^ learners with familial and historical ties (www.cal.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ those used by Apple’s newest AirPods (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ hidden costs (pubs.lib.umn.edu)

- ^ ethnography of American learners (scholarcommons.sc.edu)

- ^ generative AI apps can support acquisition (doi.org)

- ^ negotiations of meaning (doi.org)

- ^ learners usually aspire (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ cultural (doi.org)

- ^ cognitive (doi.org)

- ^ resistance (doi.org)

- ^ dementia (doi.org)

- ^ divergent thinking (doi.org)

- ^ flexibility (doi.org)

- ^ attention (doi.org)

- ^ acceptance (doi.org)

- ^ multiple perspectives and explanations (doi.org)

- ^ reduced bias (doi.org)

- ^ companies seek (www.weforum.org)

- ^ increasingly multilingual U.K. (www.ft.com)

- ^ high school (www.ft.com)

- ^ university (www.americathebilingual.com)

- ^ have struggled to demonstrate the relevance (www.doi.org)

- ^ integrating language in the contexts of other subjects (doi.org)

- ^ service and volunteering (doi.org)

- ^ virtual exchanges (doi.org)

- ^ project-based language learning (www.csiepub.org)

- ^ developing intercultural skills (docs.google.com)

Authors: Gabriel Guillén, Professor of Language Studies, Middlebury College