How working with men and boys could stop domestic violence

- Written by Richard Tolman, Professor of Social Work, University of Michigan

Can President Donald Trump’s recent repudiation of domestic violence actually help prevent it?

Rob Porter, a high-level aide to Trump, was accused of serial domestic violence by his two ex-wives. The controversy dominated news coverage earlier this month. Trump publicly denounced domestic violence one week after Porter resigned, saying “I’m totally opposed to domestic violence of any kind.”

Those who called for such a statement by the president may be motivated by the belief that when powerful men convincingly call out abusers, society’s acceptance of domestic violence can be diminished.

There is not a lot of research to support this commonsense idea.[1] But there is a growing body of work with men and boys that research shows can be effective in diminishing domestic violence.

This is a significant evolution in the field. Since the establishment of the first domestic violence shelters[2] in the 1970s, domestic violence policies and services have rightly focused most attention on survivors and meeting their needs for safety and healing.

Increasingly, though, domestic violence organizations are adopting approaches that involve men and boys in domestic violence prevention. The idea is that by addressing the root causes, these programs can stop domestic violence from occurring in the first place.

I am a professor who studies how to intervene and prevent men’s violence against women. Our research team has researched the effectiveness of programs that involve boys and men[3] in domestic violence prevention efforts[4].

Much of the work being done with men and boys is not well-known, despite the fact that this is a thriving movement. Here is a snapshot of some of those efforts, both global and local, and what we know about their effectiveness.

1. Sports and prevention

Some efforts to involve men are directed in the arena of sports because, well, men like sports. They venerate sports figures and identify with teams. Reports of domestic violence perpetrated by athletes have grown more common. This has led to visible efforts by sports organizations to respond with sanctions for perpetrators and to become part of prevention efforts, like the NFL’s No More[5]. The seriousness and effectiveness[6] of these efforts are yet to be determined[7].

But sports have also been the site of innovative and effective interventions for youth. Coaching Boys Into Men[8] provides high school athletic coaches with the resources they need help prevent relationship abuse, harassment and sexual assault by their players.

Coaching Boys Into Men curriculum being taught to the football team at an Iowa middle school.

Contributed photo, Futures Without Violence, CC BY[9]

Coaching Boys Into Men curriculum being taught to the football team at an Iowa middle school.

Contributed photo, Futures Without Violence, CC BY[9]

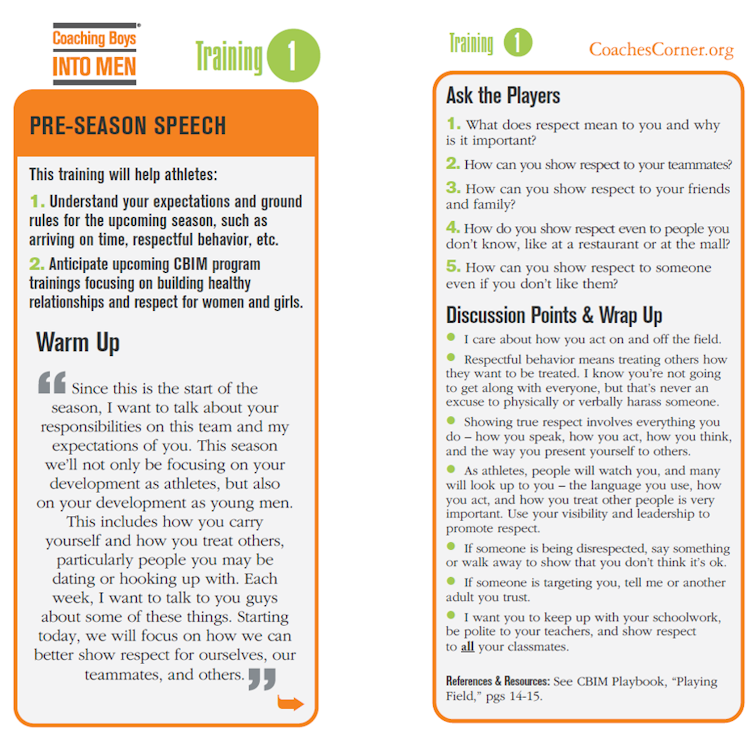

The program’s curriculum includes coach-to-athlete trainings that model respect and promote healthy relationships. It also includes a card series to help coaches incorporate themes of teamwork, integrity, fair play and respect into their daily practice and routine.

Coaching Boys Into Men[10] has been rigorously evaluated[11], found to be effective in reducing dating violence, and is being widely implemented in the U.S.[12] and replicated in other countries[13].

Coaching Boys Into Men lesson card for coaches.

Contributed by Futures Without Violence, CC BY[14]

Coaching Boys Into Men lesson card for coaches.

Contributed by Futures Without Violence, CC BY[14]

2. Transition to fatherhood

A prime risk factor for future abuse is the exposure of children to violence[15]. Preventing abuse in new families would reduce children’s exposure to violence and thus the potential for future violence.

One promising strategy is to involve men in prevention efforts as they move into fatherhood. Research shows that a caring and supportive relationship with their fathers reduces the risk of harsh physical discipline by the next generation of parents[16], both for fathers and mothers. Positive fathering predicts warmer and more positive parenting by adult sons when they become fathers[17].

Strategies that could be used in this area include engaging men at prenatal visits such as ultrasound appointments, which the vast majority of men in the U.S. attend, and at in-home visits[18] during pregnancy and after the birth of a child.

Global campaigns such as MenCare[19] seek to improve caregiving by fathers and address partner violence. MenCare’s programs ask men to become more equitable partners and provide them with opportunities to learn and practice parenting skills. They promote policy change, like paid parental leave. And they conduct media campaigns to inspire men and their communities to support men’s caregiving.

3. Preventing dating abuse

Studies document high levels of dating violence[20] beginning in middle school. When it comes to prevention, one could argue that programs must intervene early or the effort will be wasted, because stopping abuse before it becomes a entrenched pattern is more likely to be effective in preventing relationship violence.

School-based abuse prevention programs like Safe Dates[21] and Fourth R have shown some success[22] in changing attitudes and behavior.[23] The Safe Dates program, for example, uses nine 50-minute sessions, a student-performed 45-minute play and a poster contest, to explore topics on how to cultivate caring relationships, overcome gender stereotypes and help friends.

4. Bystander programs

“Bystander” prevention programs, increasingly commonplace on college campuses[24], build skills to recognize, respond to, and disrupt behavior that might lead to sexual assault or intimate partner violence[25].

Some examples of bystander behavior include telling a man who is saying disrespectful things about women to stop or helping a woman who is being harassed to get away from a situation in which she could be harmed. Teens involved in bystander interventions are more likely to intervene to prevent victimization of their peers[26].

5. Motivating men to be allies

Our research group surveyed men around the world who have been involved in efforts to prevent violence against women[27]. The survey revealed[28] that many men who get involved have a personal experience with violence – as child witnesses or survivors of their own child abuse. Still others find their way to prevention efforts through a commitment to social justice.

Importantly, we found that many men are receptive to violence prevention efforts when they tune in to survivors’ experiences.

Given that men are moved by learning about survivors’ experiences, the visibility of and emotional power of the #MeToo movement and the remarkable and vivid accounts of White House aide Rob Portman’s ex-wives can lead men to get involved in ending violence against women.

Whatever the pathway, men’s involvement in preventing domestic violence in their families, workplaces and communities can be part of the global effort to promote safety and equality for women, and to end victimization in all its forms.

References

- ^ commonsense idea. (www.who.int)

- ^ the first domestic violence shelters (webcache.googleusercontent.com)

- ^ boys and men (books.google.com)

- ^ prevention efforts (www.tacoma.uw.edu)

- ^ No More (nomore.org)

- ^ seriousness and effectiveness (scholarship.law.berkeley.edu)

- ^ yet to be determined (www.espn.com)

- ^ Coaching Boys Into Men (www.futureswithoutviolence.org)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Coaching Boys Into Men (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ rigorously evaluated (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ widely implemented in the U.S. (www.coachescorner.org)

- ^ replicated in other countries (www.futureswithoutviolence.org)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ exposure of children to violence (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ next generation of parents (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ when they become fathers (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ in-home visits (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ MenCare (men-care.org)

- ^ dating violence (www.nij.gov)

- ^ Safe Dates (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ success (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ behavior. (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ college campuses (books.google.com)

- ^ sexual assault or intimate partner violence (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ of their peers (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ prevent violence against women (digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu)

- ^ survey revealed (digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu)

Authors: Richard Tolman, Professor of Social Work, University of Michigan

Read more http://theconversation.com/how-working-with-men-and-boys-could-stop-domestic-violence-91740