Here's how forests rebounded from Yellowstone's epic 1988 fires – and why that could be harder in the future

- Written by Monica G. Turner, Professor of Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

This summer marks the 30th anniversary of the 1988 Yellowstone fires[1] – massive blazes that affected about 1.2 million acres in and around Yellowstone National Park. Their size and severity surprised scientists, managers and the public and received heavy media coverage. Many news reports proclaimed that Yellowstone was destroyed, but nothing was further from the truth.

I was there during the fires and returned that fall to view the aftermath. Burned forests extended for miles, with blackened tree trunks creating a stark and seemingly desolate landscape. But peering down from a helicopter, we were surprised to see that the fires had actually produced a mosaic of burned and unburned patches of forest.

Landscape pattern of burned and unburned trees after the Yellowstone fires, October 1988.

Monica Turner, CC BY-ND[2]

Landscape pattern of burned and unburned trees after the Yellowstone fires, October 1988.

Monica Turner, CC BY-ND[2]

I have studied the recovery of Yellowstone’s forests since 1989, watching landscapes of charred trees transition into lush young forests. Fires play an important ecological role in many ecosystems, and Yellowstone’s native plants and animals are well-adapted to historical cycles of disturbance and recovery[3]. Today the burned landscape is dominated by thriving young lodgepole pine trees[4].

We learned much about how ecosystems respond to such fires[5] because they burned mostly in national parks and wilderness areas. Post-fire management was minimal, and nature took its course through most of the burned area.

Because Yellowstone’s forests were remarkably resilient[6], the 1988 fires were not an ecological catastrophe. Today, however, climate and fire trends may be pushing forests beyond their limits. The rules of the game are changing fast.

Post-1988 young lodgepole pine forests, photographed in 2014.

Monica Turner, CC BY-ND[7]

Post-1988 young lodgepole pine forests, photographed in 2014.

Monica Turner, CC BY-ND[7]

Heat, drought and wind

Extreme weather conditions[8] drove the 1988 fires, as they have fostered many recent fires across the West. Summers in Yellowstone are usually too cool and moist for such large fires, but the summer of 1988 was and remains the driest on record there.

Amounts of fuel (dead logs and pine needles on the ground and live trees) were not unusual, and there is no evidence that suppression of prior fires had much, if any, influence on the 1988 fires. Hot temperatures, severe drought and high winds set the stage.

Gusts over 60 miles per hour prevented me from flying over the fires in early July, well before the blazes made their biggest runs. Roads, rivers and even wide canyons spanning the Yellowstone and Lewis rivers did not stop flames from spreading on windy days. Strong winds carried burning branches ahead of the main fire front, advancing fire spread. The fires also continued to burn at night.

Crown fire at Grant Village in Yellowstone National Park, July 23, 1988.

National Park Service/Jeff Henry[9]

Crown fire at Grant Village in Yellowstone National Park, July 23, 1988.

National Park Service/Jeff Henry[9]

How burned forests recover

Severe fires have burned in Yellowstone at 100- to 300-year intervals[10] for the past 10,000 years. “Crown fires” burn through the forest canopy, killing the trees while triggering a flush of new growth. Such fires are business as usual in Yellowstone[11] and many other forests at high elevations and far north latitudes[12].

Lodgepole pines have thin bark and are readily killed, but often bear fire-adapted cones that allow them to regenerate right after fires. When heated, the cones release vast quantities of seeds that produce a new generation of trees. Fires also create ideal growing conditions, with plenty of mineral soil and sunlight.

Wildflowers flourish three years after the 2008 Gunbarrel fire east of Yellowstone.

Monica Turner, CC BY-ND[13]

Wildflowers flourish three years after the 2008 Gunbarrel fire east of Yellowstone.

Monica Turner, CC BY-ND[13]

In Yellowstone, wildflowers and grasses sprouted from surviving roots because soils did not burn deeply and retained key nutrients[14] needed for plant growth. Native species steadily filled in[15] the bare spots. Aspens – long a species of concern in the northern Rockies – established from seed throughout the burned pine forests, many miles from the nearest mature aspen trees. Many are doing well at higher elevations[16] than their pre-fire distribution.

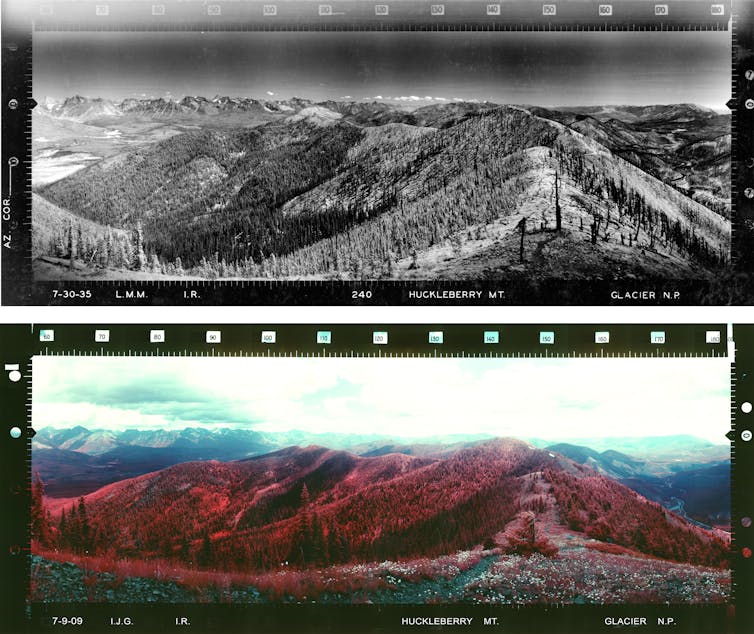

Yellowstone’s ecosystems recovered rapidly on their own. I suspect that many visitors no longer “see” evidence of the 1988 fires as they admire scenery and wildlife amidst a sea of green. Similar patterns of natural recovery following 20th-century fires have also been observed in Rocky Mountain, Glacier and Grand Teton National Parks, which also have evolved with fire for millennia. Historically, high-severity fires kill trees but do not destroy the forest.

Huckleberry Mountain in Glacier National Park after a fire on July 30, 1935 (top) and July 9, 2009 (bottom).

National Park Service[17]

Huckleberry Mountain in Glacier National Park after a fire on July 30, 1935 (top) and July 9, 2009 (bottom).

National Park Service[17]

Warming climate, more fire

The 1988 fires ushered in a new era of major wildfires[18] that are burning more western forests each year. Summers and winters are getting warmer, and the hot, dry weather associated with large fires is no longer so rare[19]. Snow melts earlier each year, fuels dry out sooner, temperature records are broken and fire season gets longer. Recent fires have burned in many national parks and monuments, including Bandelier[20], Rocky Mountain[21], Glacier[22] and Yosemite[23].

A warmer, drier climate means that drought is getting worse in places that are already hot and dry. In the western United States, human-caused climate change has dried fuels and nearly doubled the area burned by forest fires[24] from 1984 to 2015.

And while lightning ignites most fires in the northern Rockies, human ignitions are lengthening fire seasons[25] in populated areas. Even in the moist mixed forests of the southern Appalachians, severe drought allowed a human-caused fire that started in Great Smoky Mountains National Park to rage into Gatlinburg, Tennessee[26].

What lies ahead?

Even forests that are well-adapted to large, severe fires are at risk in a warming world. By the late 21st century, hot, dry weather like the summer of 1988 could be the rule rather than the exception in Yellowstone.

Large fires are expected to occur more often[27], and are already starting to reburn forests[28] long before they have had enough time to recover. In Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, fires in 2016 burned young forests[29] that regenerated from fires in 1988 and 2000. Our studies of these recent fires have documented greater burn severity and fewer post-fire tree seedlings. Survival of these young trees is not guaranteed, as they are starting out in a much warmer world.

Big and severe fires are now burning more frequently and could threaten the resilience of Western forests.National parks anchor many of the country’s last intact landscapes, and are among our best living laboratories for understanding environmental change. Research on the 1988 fires now provides a reference for assessing effects of more recent fires. Yellowstone will still maintain its beauty, native species and power to inspire us. However, only time will tell whether Yellowstone’s forests can maintain their ability to recover[30] from fire in the decades ahead.

References

- ^ 1988 Yellowstone fires (www.nps.gov)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ well-adapted to historical cycles of disturbance and recovery (doi.org)

- ^ thriving young lodgepole pine trees (doi.org)

- ^ how ecosystems respond to such fires (press.uchicago.edu)

- ^ Yellowstone’s forests were remarkably resilient (doi.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Extreme weather conditions (doi.org)

- ^ National Park Service/Jeff Henry (commons.wikimedia.org)

- ^ 100- to 300-year intervals (apcg.uoregon.edu)

- ^ business as usual in Yellowstone (doi.org)

- ^ many other forests at high elevations and far north latitudes (doi.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ retained key nutrients (doi.org)

- ^ Native species steadily filled in (doi.org)

- ^ doing well at higher elevations (doi.org)

- ^ National Park Service (www.nps.gov)

- ^ ushered in a new era of major wildfires (dx.doi.org)

- ^ no longer so rare (dx.doi.org)

- ^ Bandelier (www.nps.gov)

- ^ Rocky Mountain (www.nps.gov)

- ^ Glacier (www.nps.gov)

- ^ Yosemite (www.nps.gov)

- ^ dried fuels and nearly doubled the area burned by forest fires (doi.org)

- ^ human ignitions are lengthening fire seasons (doi.org)

- ^ Gatlinburg, Tennessee (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ occur more often (www.pnas.org)

- ^ already starting to reburn forests (dx.doi.org)

- ^ fires in 2016 burned young forests (www.youtube.com)

- ^ ability to recover (doi.org)

Authors: Monica G. Turner, Professor of Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison