Lawyers defending immigrant children in detention are relying on a court case from the 80s

- Written by Kevin Johnson, Dean and Professor of Public Interest Law and Chicana/o Studies, University of California, Davis

The Trump administration’s immigration policies have brought an old court case back to life in defense of immigrant children at the border, often referred to as “the Flores settlement.”

The case, which was filed in 1985 and settled in 1997, set the rules that the government must follow when it keeps migrant children in its custody. The latest court order based on the settlement[1] took place on July 30, in which a judge barred immigration authorities from giving children psychotropic drugs without consent of parents or legal guardians.

The Trump administration has requested to amend[2] the settlement to allow it to indefinitely detain migrant children. So far, the courts have denied these requests, and will continue to monitor the detention of migrant children.

So what was the Flores case about?

In the 1980s, the Reagan administration aggressively used detention of Central Americans as a device to deter migration from Central America[3], where violent civil wars had caused tens of thousands to flee. As a result, the government held in custody Central Americans arrested at the U.S.-Mexico border, including many who sought asylum in the U.S. because they feared persecution if returned home. Immigrant rights groups filed a series of lawsuits challenging various aspects of the detention policies, including denying access of migrants to counsel, taking steps to encourage them to “consent” to deportation, and detaining them in isolated locations far from families and attorneys.

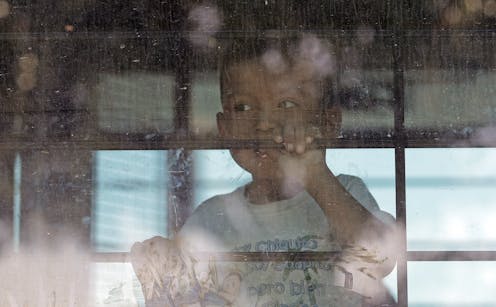

One suit was filed by the American Civil Liberties Union in 1985 on behalf of Jenny Lisette Flores[4], a 15-year-old from El Salvador. She had fled violence in her home country to live with an aunt who was in the U.S. But Flores was detained by federal authorities at the U.S. border for being undocumented.

The American Civil Liberties Union charged that holding Flores indefinitely violated the U.S. Constitution and the immigration laws. The Flores case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In its 1993 ruling in the case[5], the court held that a regulation allowing the government to release a migrant child to a close family member or legal guardian in the United States was legal.

But the primary legacy of the case was the subsequent settlement, to which both the Clinton administration and the plaintiffs agreed in 1997.

The Flores settlement established standards for the treatment of unaccompanied minors who were in the custody of federal authorities for violating the immigration laws. It requires the federal government[6] to place children with a close relative or family friend “without unnecessary delay,” rather than detaining them; and to keep immigrant children who are in custody in the “least restrictive conditions” possible. Generally speaking, this has meant migrant children can only be kept in federal immigrant detention for 20 days[7].

The Flores settlement created a framework agreed to by the U.S. government that addressed how migrant children were to be treated if they were detained. It is a landmark settlement in no small part because Central Americans continue to flee violence in their homelands and the U.S. government has responded with mass detention of immigrant children. Although the Flores settlement was agreeable to the Clinton administration, the Trump administration wants to detain families, including children, for periods longer than permitted by the Flores settlement.

References

- ^ based on the settlement (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ requested to amend (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ migration from Central America (theconversation.com)

- ^ Jenny Lisette Flores (www.nbcnews.com)

- ^ its 1993 ruling in the case (supreme.justia.com)

- ^ requires the federal government (www.vox.com)

- ^ 20 days (www.npr.org)

Authors: Kevin Johnson, Dean and Professor of Public Interest Law and Chicana/o Studies, University of California, Davis