Trump budget would undo gains from conservation programs on farms and ranches

- Written by Ashley Dayer, Assistant Professor of Fish and Wildlife Conservation, Virginia Tech

Members of the House and Senate Agriculture Committees are starting to shape the 2018 farm bill[1] – a comprehensive food and agriculture bill passed about every five years. Most observers associate the farm bill with food policy, but its conservation section is the single largest source of funding for soil, water and wildlife conservation on private land in the United States.

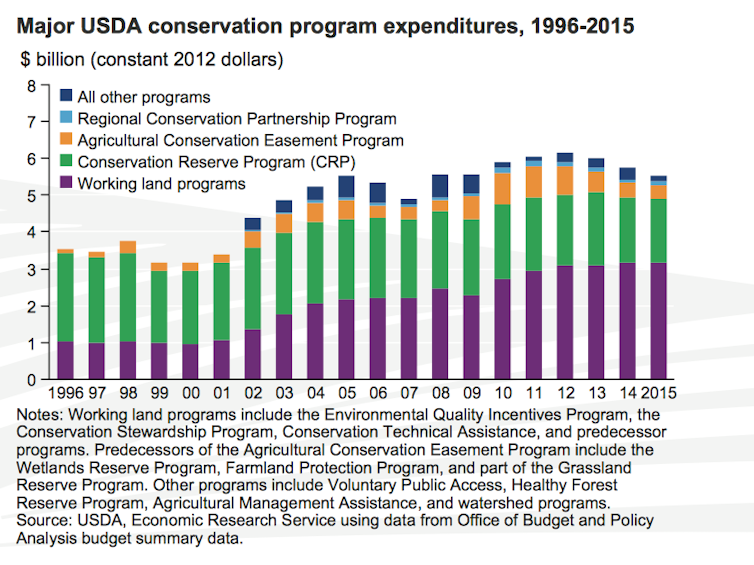

Farm bill conservation programs provide about US$5.8 billion[2] yearly for activities such as restoring wildlife habitat and using sustainable farming practices. These programs affect about 50 million acres of land nationwide[3]. They conserve millions of acres of wildlife habitat[4] and provide ecological services[5] such as improved water quality, erosion control and enhanced soil health that are worth billions of dollars.

Sixty percent of U.S. land is privately owned, and it contains a disproportionately high share[6] of habitat for threatened and endangered species. This means that to conserve land and wildlife, it is critical to work with private landowners, particularly farmers and ranchers. Farm bill conservation programs provide cost shares, financial incentives and technical assistance to farmers and other private landowners who voluntarily undertake conservation efforts on their land.

President Donald Trump’s 2019 budget request[7] would slash funding for farm bill conservation programs by about $13 billion over 10 years, on top of cuts already sustained in the 2014 farm bill. In a recent study[8], we found that it is highly uncertain whether the benefits these programs have produced will be maintained if they are cut further.

Jim and DeAnn Sattelberg received Conservation Reserve Program funding to plant ‘filter strips’ that protect water sources on their Michigan farm.

USDA, CC BY[9][10]

Jim and DeAnn Sattelberg received Conservation Reserve Program funding to plant ‘filter strips’ that protect water sources on their Michigan farm.

USDA, CC BY[9][10]

Funding cuts and future prospects

Conservation on private land produces tangible benefits for wildlife[11], water quality[12], erosion control[13] and floodwater storage[14]. The public value of these improvements extends far beyond the boundaries of any individual landowner’s property.

Studies have shown that farmers appreciate the direct benefits they receive from participating in these programs, such as more productive soil and better hunting and wildlife viewing on their lands[15]. Conservation programs can also provide farmers with an important and stable income source during crop price downturns.

Congress made substantial cuts in farm bill conservation programs in 2014 – the first reductions since the conservation title of the bill was created in 1985. In total, the 2014 farm bill reduced conservation spending by 6.4 percent, or about $3.97 billion over 10 years.[16]

USDA/ERS[17]

These cuts reduced the number of farmers who were able to enroll in the programs. For example, the Conservation Reserve Program[18] pays farmers to take environmentally sensitive land out of agricultural production and convert cropland into ecologically beneficial grasses. In 2016, due to budget cuts, it accepted just 22 percent[19] of acres that farmers offered for enrollment.

The Conservation Stewardship Program[20], which focuses on working lands in agricultural production, offers farmers financial incentives and technical advice for conservation measures such as cover crops or efficient irrigation systems. In 2015 USDA funded only 27 percent[21] of CSP applications.

The Trump administration’s proposed cuts have drawn criticism from conservation groups[22] and farmers[23]. Meanwhile, these programs appear to have bipartisan support[24] in Congress.

In a June 2017 hearing[25], Sen. Pat Roberts, R-Kan., chairman of the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry, said:

“I’ve heard repeatedly from farmers and ranchers about the importance of these programs, how they successfully incentivize farmers to take conservation to the next level, and the need for continued federal investment in these critical programs.”

In October 2017[26], Sens. Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., and Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, introduced a bipartisan bill to strengthen the Regional Conservation Partnership Program, which fosters private-public partnerships in regions of high conservation priority. The Trump administration has proposed to eliminate this program, along with the Conservation Stewardship Program.

Funding will be tight for the 2018 farm bill, as USDA has acknowledged. A set of guiding principles[27] the department released on Jan. 24 pledged to provide “a fiscally responsible Farm Bill that reflects the Administration’s budget goals.” Congress will soon face funding decisions that will have critical implications for conservation outcomes and landowners.

USDA/ERS[17]

These cuts reduced the number of farmers who were able to enroll in the programs. For example, the Conservation Reserve Program[18] pays farmers to take environmentally sensitive land out of agricultural production and convert cropland into ecologically beneficial grasses. In 2016, due to budget cuts, it accepted just 22 percent[19] of acres that farmers offered for enrollment.

The Conservation Stewardship Program[20], which focuses on working lands in agricultural production, offers farmers financial incentives and technical advice for conservation measures such as cover crops or efficient irrigation systems. In 2015 USDA funded only 27 percent[21] of CSP applications.

The Trump administration’s proposed cuts have drawn criticism from conservation groups[22] and farmers[23]. Meanwhile, these programs appear to have bipartisan support[24] in Congress.

In a June 2017 hearing[25], Sen. Pat Roberts, R-Kan., chairman of the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry, said:

“I’ve heard repeatedly from farmers and ranchers about the importance of these programs, how they successfully incentivize farmers to take conservation to the next level, and the need for continued federal investment in these critical programs.”

In October 2017[26], Sens. Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., and Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, introduced a bipartisan bill to strengthen the Regional Conservation Partnership Program, which fosters private-public partnerships in regions of high conservation priority. The Trump administration has proposed to eliminate this program, along with the Conservation Stewardship Program.

Funding will be tight for the 2018 farm bill, as USDA has acknowledged. A set of guiding principles[27] the department released on Jan. 24 pledged to provide “a fiscally responsible Farm Bill that reflects the Administration’s budget goals.” Congress will soon face funding decisions that will have critical implications for conservation outcomes and landowners.

USDA employees help South Dakota cattle ranchers repair and replace ponds for watering livestock, an initiative of the Environmental Quality Incentives Program.

USDA/NRCS South Dakota, CC BY-SA[28][29]

Without funding, fewer farmers will conserve

Further budget cuts in farm bill conservation programs would undermine environmental protection in multiple ways. Less land and wildlife would be protected, and fewer farmers would be able to enroll in these programs. Moreover, as our study[30] concluded, landowners are unlikely to continue their conservation efforts when payments end.

Federal agencies and environmental organizations generally would like to see owners keep up conservation practices even when they no longer receive federal incentives. We call this phenomenon “persistence.” Designing incentives so that they produce lasting behavior changes is a challenge in many fields, including agricultural conservation.

Our search of relevant scientific publications found very limited research on landowner behavior after incentive program contracts end. What research has been done indicates that persistence is highly variable and often does not occur.

Studies[31] have found that after contracts expire, the percentage of landowners who continue conservation management can range from 31 to 85 percent. Persistence also depends on the practices landowners are required to perform[32]. Structural actions like planting trees are more likely to have lasting effects than measures that landowners need to perform frequently and may abandon, such as treating invasive plants with herbicides.

Little is known about why landowners do or do not persist with conservation behaviors after incentive programs end. But we have identified several mechanisms that could support persistence behavior.

As landowners participate in conservation programs, they might develop positive views of conservation. They also may continue to use conservation practices because they want to be perceived as good land stewards. Practices that involve repeated action, such as moving cattle for prescribed grazing, might become habits. Finally, landowners with sufficient financial and technical resources are more likely to persist with conservation behaviors.

Long-term costs of defunding conservation programs

Our research shows that it is hard to predict how farmers and ranchers will respond if they are unable to re-enroll in farm bill conservation programs. Some might continue with conservation management, but it is likely that many landowners would resume farming formerly protected land or abandon conservation practices.

To promote conservation more effectively over time, it would make sense to consider farm bill policy changes such as issuing longer-duration contracts and designing post-contract transitions that encourage continued conservation. Further budget cuts will only reduce future conservation on private land, and could undo much of the good that these programs have already achieved.

USDA employees help South Dakota cattle ranchers repair and replace ponds for watering livestock, an initiative of the Environmental Quality Incentives Program.

USDA/NRCS South Dakota, CC BY-SA[28][29]

Without funding, fewer farmers will conserve

Further budget cuts in farm bill conservation programs would undermine environmental protection in multiple ways. Less land and wildlife would be protected, and fewer farmers would be able to enroll in these programs. Moreover, as our study[30] concluded, landowners are unlikely to continue their conservation efforts when payments end.

Federal agencies and environmental organizations generally would like to see owners keep up conservation practices even when they no longer receive federal incentives. We call this phenomenon “persistence.” Designing incentives so that they produce lasting behavior changes is a challenge in many fields, including agricultural conservation.

Our search of relevant scientific publications found very limited research on landowner behavior after incentive program contracts end. What research has been done indicates that persistence is highly variable and often does not occur.

Studies[31] have found that after contracts expire, the percentage of landowners who continue conservation management can range from 31 to 85 percent. Persistence also depends on the practices landowners are required to perform[32]. Structural actions like planting trees are more likely to have lasting effects than measures that landowners need to perform frequently and may abandon, such as treating invasive plants with herbicides.

Little is known about why landowners do or do not persist with conservation behaviors after incentive programs end. But we have identified several mechanisms that could support persistence behavior.

As landowners participate in conservation programs, they might develop positive views of conservation. They also may continue to use conservation practices because they want to be perceived as good land stewards. Practices that involve repeated action, such as moving cattle for prescribed grazing, might become habits. Finally, landowners with sufficient financial and technical resources are more likely to persist with conservation behaviors.

Long-term costs of defunding conservation programs

Our research shows that it is hard to predict how farmers and ranchers will respond if they are unable to re-enroll in farm bill conservation programs. Some might continue with conservation management, but it is likely that many landowners would resume farming formerly protected land or abandon conservation practices.

To promote conservation more effectively over time, it would make sense to consider farm bill policy changes such as issuing longer-duration contracts and designing post-contract transitions that encourage continued conservation. Further budget cuts will only reduce future conservation on private land, and could undo much of the good that these programs have already achieved.

References

- ^ 2018 farm bill (theconversation.com)

- ^ US$5.8 billion (fas.org)

- ^ 50 million acres of land nationwide (www.fws.gov)

- ^ millions of acres of wildlife habitat (www.stateofthebirds.org)

- ^ provide ecological services (doi.org)

- ^ disproportionately high share (omnilearn.net)

- ^ 2019 budget request (www.obpa.usda.gov)

- ^ study (dx.doi.org)

- ^ USDA (flic.kr)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ wildlife (www.fsa.usda.gov)

- ^ water quality (doi.org)

- ^ erosion control (amjv.org)

- ^ floodwater storage (pubs.usgs.gov)

- ^ more productive soil and better hunting and wildlife viewing on their lands (doi.org)

- ^ 6.4 percent, or about $3.97 billion over 10 years. (fas.org)

- ^ USDA/ERS (www.ers.usda.gov)

- ^ Conservation Reserve Program (www.fsa.usda.gov)

- ^ 22 percent (fas.org)

- ^ Conservation Stewardship Program (www.nrcs.usda.gov)

- ^ 27 percent (fas.org)

- ^ conservation groups (www.audubon.org)

- ^ farmers (civileats.com)

- ^ bipartisan support (sustainableagriculture.net)

- ^ June 2017 hearing (www.agriculture.senate.gov)

- ^ October 2017 (www.agriculture.senate.gov)

- ^ guiding principles (www.usda.gov)

- ^ USDA/NRCS South Dakota (flic.kr)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ our study (dx.doi.org)

- ^ Studies (www.chesapeakebay.net)

- ^ practices landowners are required to perform (www.chesapeakebay.net)

Authors: Ashley Dayer, Assistant Professor of Fish and Wildlife Conservation, Virginia Tech