What 40 years of 'Space Invaders' says about the 1970s – and today

- Written by Lindsay Grace, Associate Professor of Communication; Director, American University Game Lab and Studio, American University School of Communication

The “Space Invaders” arcade video game, celebrating its 40th anniversary[1], is an iconic piece of software, credited as one of the earliest digital shooting games. Like many early games, it and its surrounding myths showcase the cultural collisions and issues current at its creation by Japanese game designer Tomohiro Nishikado[2].

As a game designer and teacher of games, I know how meaning is carried from designer to the mechanics of play[3]. As a game studies researcher[4], I also know how games reveal myth, meaning and culture.

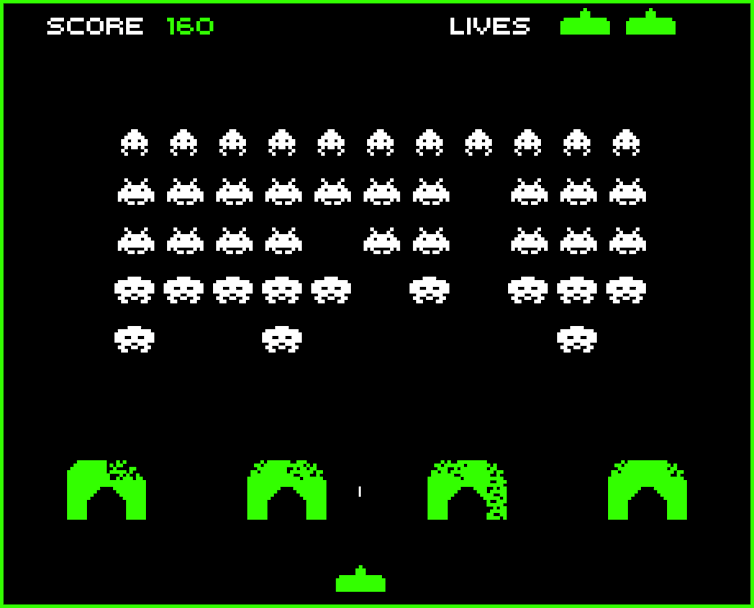

An analysis of “Pac-Man,”[5] for instance, shows how that game embodies many values of its day – including consumerism, drug use and gender politics. The message in “Space Invaders” is as basic as the graphics: When faced with conflict, players have no option except to blast it away.

Avoiding an enemy only delays the inevitable; players cannot move forward or back, but can only defend their space. There’s not even a reason why the invasion is occurring. Players know only that the invaders must be destroyed. It’s a distinct cultural perspective, emphasizing shooting over everything else.

Defense is the only option against a never-ending onslaught.

BagoGames, CC BY[6][7]

Defense is the only option against a never-ending onslaught.

BagoGames, CC BY[6][7]

A historical pioneer

The history of many shooting games can be traced to “Space Invaders.” It’s not the first – MIT’s “Spacewar![8]” was earlier, in 1961[9] – but “Space Invaders” is among the most copied. Even people who never played the original “Space Invaders” have likely played the more than 100 clones of it[10] – including the first advertising game, “Pepsi Invaders[11].”

‘Spacewar!’The release of “Space Invaders” foreshadowed the growth of the Japanese games industry, which itself was seen as a fearsome cultural invasion[12] of the U.S. by Japan. The tension was expressed in popular media as a defense of American individualism against the power and efficacy of Japanese collectivism and corporate culture[13]. This tension displayed itself in popular media like the comedy film “Gung Ho[14]” as a combined Japanophobia and Japanophilia.

“Space Invaders” also highlighted how tenuous some elements of Western identity were. The U.S. had built its sense of self on being the greatest, but was being challenged by Japanese economic growth. But it was complicated: As Japanese automakers won customers from the American car companies, they began to build their cars in the U.S.[15] – so were they Japanese or American cars?

A game of ‘Space Invaders.’In the same way, if the American game maker Atari’s biggest hit was a Japanese-made game[16], how American was Atari’s success? In any case, millions of U.S. consumers bought the Atari 2600 game system to be able to play the hit arcade game “Space Invaders” at home. Five years later, in 1983, the games industry crumbled in large part because American-made games were not interesting and too similar to each other[17].

In 1985 the Japanese-made Nintendo Entertainment System[18] ushered in a new era of home console play[19]. That continued the challenge to the American identity: U.S. companies failed to innovate and lead, and a Japanese company filled the innovation void.

The myths of (space) invasion

“Space Invaders” also has collected some myths around it, which reveal more about society than about the game itself. The most notable legend is that “Space Invaders” was so popular that the Japanese economy ran out of the coins[20] needed to play it in arcades. It’s not true[21], but like many myths about games, both positive and negative, it sounds so good it’s easy to champion anyway.

That fable is a prequel to larger popular fictions about games. People blame games for the decline of economies and for joblessness[22]. The innovations created in games support technological innovations that change society and the way people socialize[23], yet people are also eager to blame large systemic issues like gun violence in schools on video games[24].

Another tale is that “Space Invaders” demand was so strong that even with multiple game machines installed, there were lines to play[25]. Whether or not they were queuing up for their own turns, it’s definitely true that people watched others play[26]. That helped set the stage for the growth of arcades and LAN-gaming parties, precursors to professional players and today’s multi-billion-dollar industry of e-sports[27].

An arena packed with people watching others play video games.

Sam Churchill, CC BY[28][29]

An arena packed with people watching others play video games.

Sam Churchill, CC BY[28][29]

History shows that games change society, pointing it toward play and creating new economies. The advent of arcades was as novel as the contemporary use of the micro-transactions common in mobile games[30] now. Their incubation of community and spectator play spawned countless YouTube gaming channels[31].

Like the space invaders that descend on the player, unknown but always threatening, games scare some people. They seem to be unrelentingly approaching, different and hard to keep pace with. Games challenge players to adapt and dismantle the conventions under which people hide.

But, like playing “Space Invaders” itself, the joy comes in interacting with that change, mastering it and moving on to the next level.

References

- ^ celebrating its 40th anniversary (www.giantbomb.com)

- ^ Tomohiro Nishikado (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ designer to the mechanics of play (www.arts.rpi.edu)

- ^ game studies researcher (scholar.google.com)

- ^ analysis of “Pac-Man,” (doi.org)

- ^ BagoGames (www.flickr.com)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Spacewar! (museum.mit.edu)

- ^ in 1961 (www.theverge.com)

- ^ 100 clones of it (www.giantbomb.com)

- ^ Pepsi Invaders (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ cultural invasion (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ power and efficacy of Japanese collectivism and corporate culture (www.routledge.com)

- ^ Gung Ho (www.imdb.com)

- ^ cars in the U.S. (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Atari’s biggest hit was a Japanese-made game (www.rolentapress.com)

- ^ not interesting and too similar to each other (www.arcadeattack.co.uk)

- ^ Nintendo Entertainment System (www.nintendo.com)

- ^ new era of home console play (home.bt.com)

- ^ ran out of the coins (www.newyorker.com)

- ^ It’s not true (unrealfacts.com)

- ^ decline of economies and for joblessness (www.nber.org)

- ^ change society and the way people socialize (www.penguinrandomhouse.com)

- ^ gun violence in schools on video games (theconversation.com)

- ^ lines to play (www.bbc.com)

- ^ watched others play (www.newstatesman.com)

- ^ multi-billion-dollar industry of e-sports (mitpress.mit.edu)

- ^ Sam Churchill (www.flickr.com)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ micro-transactions common in mobile games (www.fool.com)

- ^ countless YouTube gaming channels (www.businessinsider.com)

Authors: Lindsay Grace, Associate Professor of Communication; Director, American University Game Lab and Studio, American University School of Communication

Read more http://theconversation.com/what-40-years-of-space-invaders-says-about-the-1970s-and-today-97518