Iran's mild response to unprecedented truckers' strike could be due to Trump's influence

- Written by Nader Habibi, Henry J. Leir Professor of Practice in Economics of the Middle East, Brandeis University

Last month, the Trump administration backed out of the 2015 deal[1] his predecessor made with Iran that traded giving up nuclear ambitions for sanctions relief.

The U.S. is expected to soon tighten the screws[2] even further by imposing the “strongest sanctions in history” in an effort to limit Iran’s missile program as well as achieve broader aims of restraining its foreign policy or even regime change.

Even though the U.S. acted without the other five countries that signed the deal, this has already hurt Iran’s economy[3] and pushed its currency to a record low. As a result, truckers and other aggrieved workers, who were already under pressure because of low wages, have begun protesting for better pay and conditions.

Does this suggest President Donald Trump’s harsh anti-Iran strategy is working?

Based on two decades researching[4] Iran’s economy and politics, I believe this question requires careful examination.

State of Iran’s economy

In the years before Iran signed the nuclear agreement with the U.S., China, Russia and Europe in 2015, its economy fell into a severe recession[5] as a result of the punishing sanctions then in place.

After the deal brought relief, Iran’s economy rebounded[6] and began to draw outside investment, lifting hopes among ordinary Iranians that things would improve. But the moderate gains in economic conditions – and the creation of few new jobs – fell short of initial expectations[7] about the deal’s benefits.

International investors have since grown cautious[8] because of uncertainty about the new president’s commitment to the deal. When Trump announced the U.S. withdrawal on May 8, the old sanctions were reimposed – though European countries are asking for exemptions[9].

As a result, growth has stalled, the Iranian rial is rapidly losing value and inflation is surging[10] as people convert their savings into gold and hard currencies. And the post-deal surge in oil exports, which more than doubled from four years earlier to 2.2 million barrels per day in early 2018, is now at risk[11].

Iran’s currency has plunged in recent months and reached an all-time low in May.

AP Photo/Vahid Salemi

Iran’s currency has plunged in recent months and reached an all-time low in May.

AP Photo/Vahid Salemi

Striking truckers

The worsening economic conditions are why Iran’s truck drivers launched an unprecedented nationwide strike[12] in mid-May for an increase in their wages. The government regulates the rate they get paid.

Since Iran’s trucking industry plays a crucial role in the domestic distribution of all essential goods, from gasoline to food, a prolonged strike could cause considerable[13] economic damage and fuel further discontent.

Normally the Islamic regime does not tolerate political protests against its rule and core policies, as was demonstrated by its severe crackdown[14] against mass protests after the 2009 elections. Yet at the same time, it shows more tolerance[15] for protests for narrow economic and social causes as long as they are small in size and refrain from anti-regime slogans.

The truckers’ strike, however, is neither localized nor marginal.

Yet, surprisingly, the regime and its security forces have shown considerable patience toward the truckers’ protest. Even opposition groups[16], which are usually eager to publicize political crackdowns, have not reported a violent reaction or mass arrests so far.

The government even offered the truckers a partial concession[17] in the form of a 20 percent freight rate hike. While that was less than half of what they were demanding, this type of concession by the regime has never happened before.

In the past, smaller strikes and protests[18] over economic grievances often dragged on for weeks without leading to either a concession or a crackdown by the government.

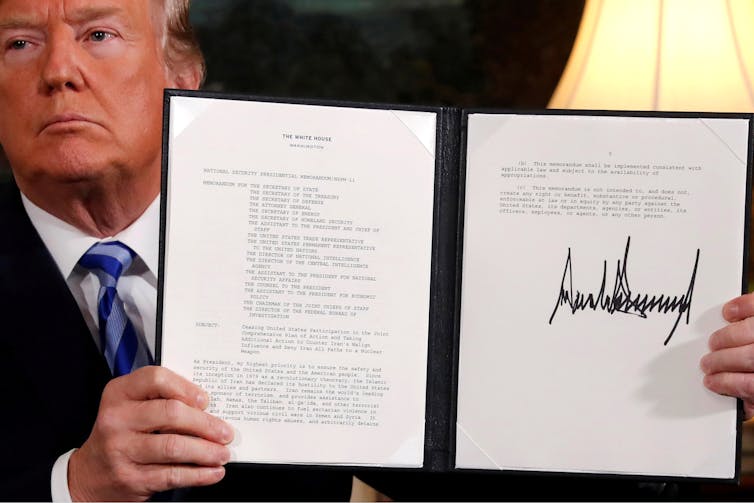

President Trump holds a proclamation declaring his intention to withdraw from the Iran nuclear agreement.

Reuters/Jonathan Ernst

President Trump holds a proclamation declaring his intention to withdraw from the Iran nuclear agreement.

Reuters/Jonathan Ernst

Fear of US reaction

So why has the government adopted a conciliatory approach to the truckers? I believe their restraint is mostly a result of the Islamic regime’s concern about Trump’s potential reaction to a violent domestic crackdown.

When Iranians took to the streets[19] after the 2009 elections, the regime was confident that the Obama administration would not take any action to support the protesters. Its leaders believed that the U.S. was in no mood for another intervention in a Middle Eastern country after Bush’s costly 2003 invasion of Iraq. So it used a heavy hand[20] to suppress them, and in fact the U.S. did little besides issue strongly worded condemnations.

This time the government is worried that Trump will behave differently. That’s also why the regime used caution[21] in its response to the economic protests in December and January, which quickly evolved into mass riots[22] in many small cities.

With Trump’s recent appointments of John Bolton as national security adviser and Mike Pompeo as CIA director, his foreign policy team is now dominated by hard-line policymakers who do not hide their desire for regime change[23] in Iran. It seems likely that Iran’s leadership is trying to avoid any violent punishment of its discontents for fear that it’ll be used as a pretext for a military strike or the promised ramp-up of sanctions.

Spreading protests

But the regime’s mild reaction to the truckers’ strike carries significant political risks of its own.

That’s because it seems to be encouraging more protests as the truckers’ partial success has emboldened taxi drivers,[24] ranchers and poultry farmers[25] to go on strike – although on a smaller scale so far – to express grievances over government policies that are hurting their businesses.

If these strikes and work stoppages continue to expand, not only could they paralyze the economy, but they could also pose a severe political threat to the ruling regime.

Unable to suppress the protests for fear of U.S. intervention, the government will likely have to appease more protesters’ demands, perhaps by offering more subsidies or allowing the protesting industries to raise the prices of their goods and services, most of which are also regulated by the state.

But that means more government spending that it can hardly afford, leading to larger budget deficits[26] and even higher inflation, which drives up the prices for many essential goods and services.

Finally, if people see that the risk of being physically harmed or arrested in protests has declined, they will be more likely to join these types of protests. In other words, the government’s tolerant response will invite more protests and strikes. Perhaps this is good for Iranians’ political freedoms but bad for a regime trying to maintain control.

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently warned Iran the ‘strongest sanctions’ ever are coming.

Reuters/Jonathan Ernst

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently warned Iran the ‘strongest sanctions’ ever are coming.

Reuters/Jonathan Ernst

What’s next?

Essentially, Trump is putting Iran in a very uncomfortable position.

On the one hand, U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal and the threat of new sanctions is directly weakening Iran’s economy and making life worse for its citizens. At the same time, fears of military intervention and more sanctions are deterring the Iranian regime from using force against growing strikes and protests.

Unable to crack down on protesters, the regime will have to keep making concessions to workers and trade syndicates in the hope that this quells the unrest, putting a severe strain on government finances and creating conditions that might result in high inflation and more unrest.

In my opinion, this severe economic pressure could even force Iran to accept some limits on its foreign policy and military programs that the Trump administration has demanded. After all, had it not been for the severe international sanctions, Iran would have not conceded to the significant rollback of its nuclear program within the framework of the 2015 nuclear agreement.

References

- ^ backed out of the 2015 deal (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ tighten the screws (www.bbc.com)

- ^ hurt Iran’s economy (www.latimes.com)

- ^ researching (scholar.google.com)

- ^ fell into a severe recession (tradingeconomics.com)

- ^ rebounded (www.worldbank.org)

- ^ expectations (www.cissm.umd.edu)

- ^ have since grown cautious (oilprice.com)

- ^ asking for exemptions (money.cnn.com)

- ^ inflation is surging (www.cnn.com)

- ^ is now at risk (www.asahi.com)

- ^ nationwide strike (www.al-monitor.com)

- ^ could cause considerable (www.opendemocracy.net)

- ^ severe crackdown (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ more tolerance (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ opposition groups (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ partial concession (www.opendemocracy.net)

- ^ smaller strikes and protests (en.radiofarda.com)

- ^ took to the streets (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ heavy hand (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ used caution (theconversation.com)

- ^ mass riots (www.forbes.com)

- ^ desire for regime change (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ taxi drivers, (www.opendemocracy.net)

- ^ ranchers and poultry farmers (www.voanews.com)

- ^ larger budget deficits (tradingeconomics.com)

Authors: Nader Habibi, Henry J. Leir Professor of Practice in Economics of the Middle East, Brandeis University