America gets a D+ for school infrastructure - but federal COVID relief could pay for many repairs

- Written by Michael Addonizio, Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, Wayne State University

Many kids are attending public schools this spring with the use of COVID-19 safety protocols, including more desk spacing, more frequent cleaning and mandates to wear masks.

But far too many of the school buildings themselves remain dilapidated[1], toxic and in desperate need of structural improvements[2].

On average, U.S. public schools are more than 50 years old[3] – and by and large they are not being properly maintained, updated or replaced. The American Society of Civil Engineers graded America’s public K-12 infrastructure a D+ in their 2021 Infrastructure Report Card[4], the same abysmal grade as in their prior 2017 report.

But help may finally be on the way.

The US$1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan[5] signed into law by President Joe Biden on March 11 provides nearly $130 billion for K-12 education and could trigger much-needed investment in the U.S.‘s crumbling public school buildings. The package provides an additional $350 billion for state, local and territorial governments – some of which could also be invested in schools.

This new money comes on the heels of $13.5 billion in K-12 relief from last spring’s CARES Act[6] and $54 billion from December’s Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act[7].

Such unprecedented federal investment could fuel a long-term national effort to repair and modernize our public schools – the second-largest public infrastructure[8] in our nation, behind roads and highways.

Why schools are crumbling

For decades now, the funding of our public school infrastructure has remained the most inequitable aspect[9] of our school finance system.

School districts rely primarily on local property taxes to build and renovate their schools. On average, states pay for 45%[10] of local school operations, but cover only 18% of school capital costs. Twelve states provide no capital aid. The federal government contributes an average of 8%[11] for local school operations, but less than 1%[12] of capital spending.

The 2016 “State of Our Schools” report[13] by the Center for Green Schools concluded that the U.S. underfunds school facilities by about $46 billion each year – a 32% annual shortfall that compounds over time and has worsened in recent years[14].

As a former assistant state superintendent for research and policy and now a professor of educational leadership and policy[15], I’ve seen firsthand the problems that arise from this inadequate and inequitable funding. In my home state of Michigan, wealthy districts can build and upgrade fine schools, often with low property tax rates. Meanwhile, poor districts endure aging, dilapidated and sometimes unsafe schools – despite paying high property tax rates.

In prosperous Ann Arbor, for example, children will enjoy the benefits of a $1 billion capital bond[16] approved in late 2019 by local voters, including me. The bond program, fully funded by local property taxes, will upgrade the district’s 35 buildings, including new and enhanced technology, building entrance renovations, outdoor classrooms, kitchens, teaching gardens and the construction of two new schools.

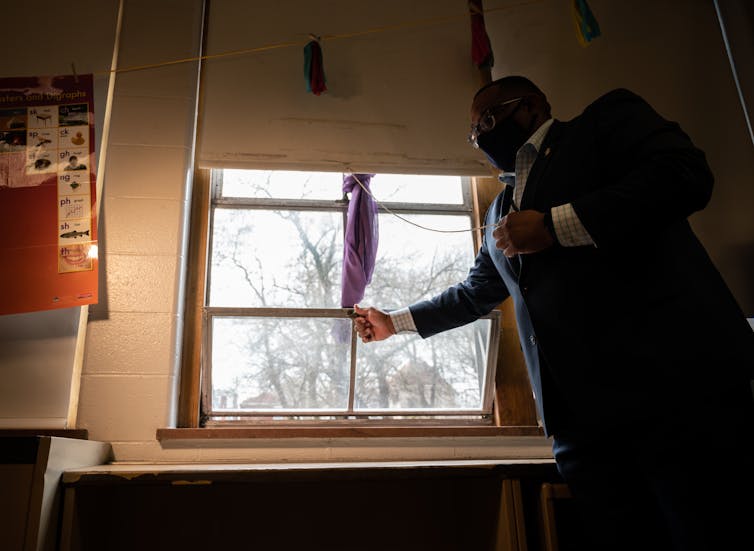

In nearby Hamtramck Public School District, however, where property values are lower, and some school buildings are so old they’ve been designated historical landmarks, school leaders need their new federal relief to fix windows that won’t open[17].

The educational toll of inequity

Recent news reports like the one about kids sitting on a curb outside Taco Bell[18] with their Chromebooks, trying to connect to the internet to do their schoolwork, have thrown a spotlight on inequities.

In Chicago, where the average school building is 80 years old[19], the public schools have spent $100 million upgrading HVAC systems since last spring. Still, the district has a $3.5 billion backlog[20] of building repairs.

A school district executive administrator in Louisville, Ky., demonstrates how classroom windows will be left open as a COVID-19 safety precaution.

on Cherry/Getty Images[21]

A school district executive administrator in Louisville, Ky., demonstrates how classroom windows will be left open as a COVID-19 safety precaution.

on Cherry/Getty Images[21]

In Baltimore, nearly two-thirds of the public school buildings are over 50 years old. They are poorly maintained. According to six years of inspections records, only 17% of Baltimore’s schools were in “good” or “superior” shape – the lowest percentage in the state[22].

In old school buildings, it’s more likely that pipes will burst, heat and air conditioning will fail, and plumbing and electrical problems will arise. And these problems take an educational toll on kids and teachers.

Research confirms[23] that a dry building with good indoor air quality and thermal comfort reduces student illness and absences and elevates student achievement. Facility quality can also significantly impact teacher retention[24].

The American Rescue Plan can help immensely. The biggest pot of the $128 billion earmarked for K-12 schools is $122.8 billion allocated to school districts and states. Fully 90% goes to local districts through the Title I formula, which favors districts with low-income families[25].

Districts will get to determine how they use these funds[26]. The sole restriction requires they use at least 20% of the money to address “learning loss.” Examples mentioned in the law include “summer learning or summer enrichment, extended day, comprehensive after-school programs or extended school-year programs.”

Most importantly, the amount of K-12 aid can’t be used to pay for state and local cuts to school funding. Combined with the two previous federal COVID-19 relief packages, this K-12 emergency funding totals about $195 billion, nearly twice the amount[27] schools received in the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

And finally, the American Rescue Plan money is a one-time injection. It can be used until 2024, but should not be baked into school operating budgets without solid plans for state or local replacement funding. So hiring more teachers and support staff, though attractive as an educational investment, would probably lead to massive and disruptive layoffs in a few years. Infrastructure upgrades, however, sidestep this problem.

Two years ago, I wrote an article[28] about fixing America’s crumbling public schools and argued that passage of the Rebuild America’s Schools Act of 2019[29], a bill that would invest $100 billion over 10 years in our school buildings, was a no-brainer. That bill never passed, but was reintroduced this session and has been largely folded into President Biden’s infrastructure bill called the American Jobs Plan[30], which was announced on March 31.

The plan calls for $100 billion to upgrade and build new public schools. The bill’s proposed tax hikes, however, prompted immediate criticism from Republicans and prominent business groups, including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Much negotiation and change to the $2 trillion package can be expected.

But in the meantime, there’s the American Rescue Plan. The K-12 money in this sprawling relief package is not dedicated to school infrastructure and is not a final fix to an enormous problem that has been decades in the making. But using a good share of this massive, one-time federal investment to address this chronic need in our poorest schools makes total sense to me.

References

- ^ dilapidated (theconversation.com)

- ^ need of structural improvements (www.reed.senate.gov)

- ^ are more than 50 years old (nces.ed.gov)

- ^ 2021 Infrastructure Report Card (infrastructurereportcard.org)

- ^ American Rescue Plan (www.cnbc.com)

- ^ CARES Act (www.chalkbeat.org)

- ^ Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (www.chalkbeat.org)

- ^ second-largest public infrastructure (www.buildusschools.org)

- ^ most inequitable aspect (dx.doi.org)

- ^ 45% (nces.ed.gov)

- ^ average of 8% (theconversation.com)

- ^ less than 1% (www.buildusschools.org)

- ^ State of Our Schools” report (centerforgreenschools.org)

- ^ worsened in recent years (www.cbpp.org)

- ^ professor of educational leadership and policy (education.wayne.edu)

- ^ $1 billion capital bond (www.mlive.com)

- ^ fix windows that won’t open (www.chalkbeat.org)

- ^ outside Taco Bell (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ is 80 years old (www.cps.edu)

- ^ $3.5 billion backlog (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ on Cherry/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ lowest percentage in the state (www.argis.com)

- ^ Research confirms (doi.org)

- ^ teacher retention (eric.ed.gov)

- ^ favors districts with low-income families (nces.ed.gov)

- ^ how they use these funds (www.chalkbeat.org)

- ^ twice the amount (www.edweek.org)

- ^ an article (theconversation.com)

- ^ Rebuild America’s Schools Act of 2019 (www.congress.gov)

- ^ American Jobs Plan (www.washingtonpost.com)

Authors: Michael Addonizio, Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, Wayne State University