Pew's new global survey of climate change attitudes finds promising trends but deep divides

- Written by Kate T. Luong, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, George Mason University

People’s views about climate change, from how worried they are about it affecting them to how willing they are to do something about it, have shifted in developed countries around the world in recent years, a new survey by the Pew Research Center[1] finds.

The study polled more than 16,000 adults[2] in 17 countries considered to be advanced economies. Many of these countries have been large contributors to climate change and will be expected to lead the way in fixing it.

In general, the survey found that a majority of people are concerned about global climate change and are willing to make lifestyle changes to reduce its effects.

However, underneath this broad pattern lie more complicated trends, such as doubt that the international community can effectively reduce climate change and deep ideological divides that can hinder the transition to cleaner energy and a climate-friendly world. The survey also reveals an important disconnect between people’s attitudes and the enormity of the challenge climate change poses.

Here’s what stood out to us as professionals[3] who study the public’s response[4] to climate change[5].

Strong concern and willingness to take action

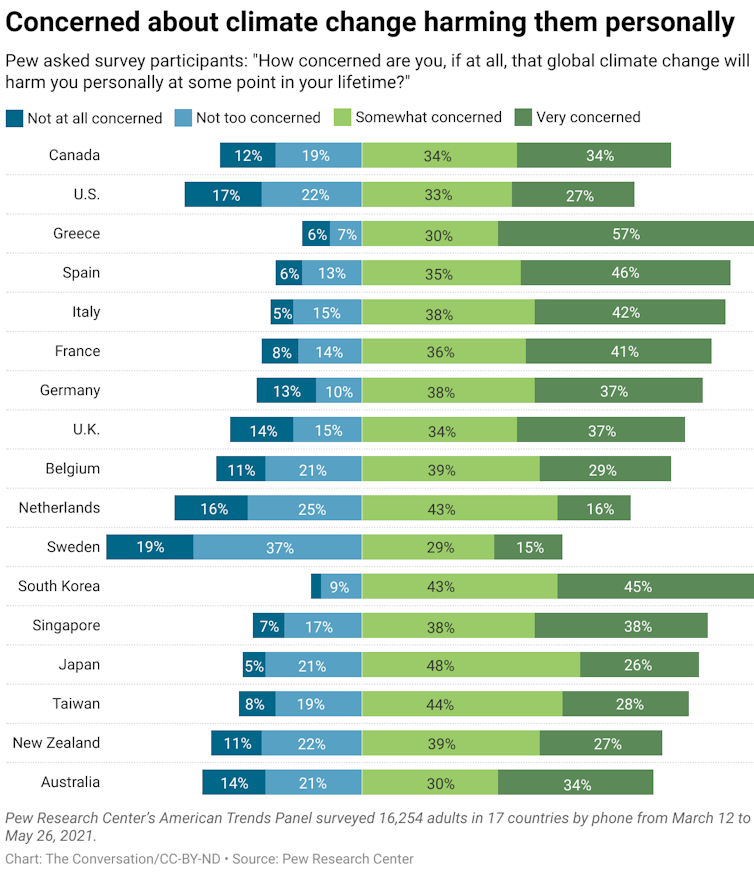

In all the countries surveyed in early 2021 except Sweden, between 60% and 90% of the citizens reported feeling somewhat or very concerned about the harm they would personally face from climate change. While there was a clear increase in concern in several countries between 2015, when Pew conducted the same survey, and 2021, this number did not change significantly in the U.S.

CC BY-ND[6]

Similarly, in all countries except Japan, at least 7 out of 10 people said they are willing to make some or a lot of changes in how they live and work to help address global climate change.

Across most countries, young people were much more likely than older generations to report higher levels of both concern about climate change and willingness to change their behaviors.

Perceptions about government responses

Clearly, on a global level, people are highly concerned about this existential threat and are willing to change their everyday behaviors to mitigate its impacts. However, focusing on changing individual behaviors alone will not stop global warming.

In the U.S., for example, about 74% of greenhouse gas emissions are from fossil fuel combustion[7]. People can switch to driving electric vehicles or taking electric buses and trains, but those still need power. To pressure utilities to shift to renewable energy requires policy-level changes, both domestically and internationally[8].

When we look at people’s attitudes regarding how their own country is handling climate change and how effective international actions would be, the results painted a more complex picture.

On average, most people evaluated their own government’s handling of climate change as “somewhat good,” with the highest approval numbers in Sweden, the United Kingdom, Singapore and New Zealand. However, data shows that such positive evaluations are not actually warranted. The 2020 U.N. Emissions Gap Report[9] found that greenhouse gas emissions have continued to rise. Many countries, including the U.S., are projected to miss their target commitments to reduce emissions by 2030; and even if all countries achieve their targets, annual emissions need to be reduced much further to reach the goals set by the Paris climate agreement.

When it comes to confidence in international actions to address climate change, the survey respondents were more skeptical overall. Although the majority of people in Germany, the Netherlands, South Korea and Singapore felt confident that the international community can significantly reduce climate change, most respondents in the rest of the countries surveyed did not. France and Sweden had the lowest levels of confidence with more than 6 in 10 people being unconvinced.

Together, these results suggest that people generally believe climate change to be a problem that can be solved by individual people and governments. Most people say they are willing to change their lifestyles, but they may not have an accurate perception of the scale of actions needed to effectively address global climate change. Overall, people may be overly optimistic about their own country’s capability and commitment to reduce emissions and fight climate change, and at the same time, underestimate the value and effectiveness of international actions.

These perceptions may reflect the fact that the conversation surrounding climate change[10] so far has been dominated by calls to change individual behaviors instead of emphasizing the necessity of collective and policy-level actions. Addressing these gaps is an important goal for people who are working in climate communication[11] and trying to increase public support for stronger domestic policies and international collaborations.

Deep ideological divide in climate attitudes

As with most surveys about climate change attitudes, the new Pew report reveals a deep ideological divide in several countries.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today[12].]

Perhaps not surprisingly, the U.S. leads in ideological differences for all but one question. In the U.S., 87% of liberals are somewhat or very concerned about the personal harms from climate change, compared to only 28% of conservatives – a stark 59-point difference. This difference persists for willingness to change one’s lifestyle (49-point difference), evaluation of government’s handling of climate change (41-point difference), and perceived economic impacts of international actions (41-point difference).

And the U.S. is not alone; large ideological differences were also found in Canada, Australia and the Netherlands. In fact, only Australians were more divided than Americans on how their government is handling the climate crisis.

This ideological divide is not new, but the size of the gap between people on the two ends of the ideological spectrum is astounding. The differences lie not only in how to handle the issue or who should be responsible but also in the scope and severity of climate change in the first place. Such massive, entrenched differences in public understanding and acceptance of the scientific facts regarding climate change will present significant challenges in enacting much-needed policy changes.

Better understanding of the cultural, political and media dynamics that shape those differences might reveal helpful insights that could ease the path toward progress in slowing climate change.

CC BY-ND[6]

Similarly, in all countries except Japan, at least 7 out of 10 people said they are willing to make some or a lot of changes in how they live and work to help address global climate change.

Across most countries, young people were much more likely than older generations to report higher levels of both concern about climate change and willingness to change their behaviors.

Perceptions about government responses

Clearly, on a global level, people are highly concerned about this existential threat and are willing to change their everyday behaviors to mitigate its impacts. However, focusing on changing individual behaviors alone will not stop global warming.

In the U.S., for example, about 74% of greenhouse gas emissions are from fossil fuel combustion[7]. People can switch to driving electric vehicles or taking electric buses and trains, but those still need power. To pressure utilities to shift to renewable energy requires policy-level changes, both domestically and internationally[8].

When we look at people’s attitudes regarding how their own country is handling climate change and how effective international actions would be, the results painted a more complex picture.

On average, most people evaluated their own government’s handling of climate change as “somewhat good,” with the highest approval numbers in Sweden, the United Kingdom, Singapore and New Zealand. However, data shows that such positive evaluations are not actually warranted. The 2020 U.N. Emissions Gap Report[9] found that greenhouse gas emissions have continued to rise. Many countries, including the U.S., are projected to miss their target commitments to reduce emissions by 2030; and even if all countries achieve their targets, annual emissions need to be reduced much further to reach the goals set by the Paris climate agreement.

When it comes to confidence in international actions to address climate change, the survey respondents were more skeptical overall. Although the majority of people in Germany, the Netherlands, South Korea and Singapore felt confident that the international community can significantly reduce climate change, most respondents in the rest of the countries surveyed did not. France and Sweden had the lowest levels of confidence with more than 6 in 10 people being unconvinced.

Together, these results suggest that people generally believe climate change to be a problem that can be solved by individual people and governments. Most people say they are willing to change their lifestyles, but they may not have an accurate perception of the scale of actions needed to effectively address global climate change. Overall, people may be overly optimistic about their own country’s capability and commitment to reduce emissions and fight climate change, and at the same time, underestimate the value and effectiveness of international actions.

These perceptions may reflect the fact that the conversation surrounding climate change[10] so far has been dominated by calls to change individual behaviors instead of emphasizing the necessity of collective and policy-level actions. Addressing these gaps is an important goal for people who are working in climate communication[11] and trying to increase public support for stronger domestic policies and international collaborations.

Deep ideological divide in climate attitudes

As with most surveys about climate change attitudes, the new Pew report reveals a deep ideological divide in several countries.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today[12].]

Perhaps not surprisingly, the U.S. leads in ideological differences for all but one question. In the U.S., 87% of liberals are somewhat or very concerned about the personal harms from climate change, compared to only 28% of conservatives – a stark 59-point difference. This difference persists for willingness to change one’s lifestyle (49-point difference), evaluation of government’s handling of climate change (41-point difference), and perceived economic impacts of international actions (41-point difference).

And the U.S. is not alone; large ideological differences were also found in Canada, Australia and the Netherlands. In fact, only Australians were more divided than Americans on how their government is handling the climate crisis.

This ideological divide is not new, but the size of the gap between people on the two ends of the ideological spectrum is astounding. The differences lie not only in how to handle the issue or who should be responsible but also in the scope and severity of climate change in the first place. Such massive, entrenched differences in public understanding and acceptance of the scientific facts regarding climate change will present significant challenges in enacting much-needed policy changes.

Better understanding of the cultural, political and media dynamics that shape those differences might reveal helpful insights that could ease the path toward progress in slowing climate change.

References

- ^ Pew Research Center (www.pewresearch.org)

- ^ polled more than 16,000 adults (www.pewresearch.org)

- ^ professionals (scholar.google.com)

- ^ who study the public’s response (scholar.google.com)

- ^ to climate change (scholar.google.com)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ 74% of greenhouse gas emissions are from fossil fuel combustion (www.eia.gov)

- ^ policy-level changes, both domestically and internationally (environment.yale.edu)

- ^ 2020 U.N. Emissions Gap Report (www.unep.org)

- ^ the conversation surrounding climate change (theconversation.com)

- ^ people who are working in climate communication (doi.org)

- ^ Sign up today (theconversation.com)

Authors: Kate T. Luong, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, George Mason University