Wildfires are contaminating drinking water systems, and it's more widespread than people realize

- Written by Andrew J. Whelton, Associate Professor of Civil, Environmental & Ecological Engineering, Director of the Healthy Plumbing Consortium and Center for Plumbing Safety, Purdue University

More than 58,000[1] fires scorched the United States last year, and 2021 is on track to be even drier[2]. What many people don’t realize is that these wildfires can do lasting damage beyond the reach of the flames – they can contaminate entire drinking water systems with carcinogens that last for months after the blaze. That water flows to homes, contaminating the plumbing, too.

Over the past four years, wildfires have contaminated drinking water distribution networks and building plumbing for more than 240,000 people.

Small water systems serving housing developments, mobile home parks, businesses and small towns have been particularly hard-hit. Most didn’t realize their water was unsafe until weeks to months after the fire.

The problem starts when wildfire smoke gets into the system or plastic in water systems heats up[3]. Heating can cause plastics to release harmful chemicals, like benzene, which can contaminate drinking water and permeate the system.

As an environmental engineer[4], I and my colleagues work with communities recovering from wildfires and other natural disasters. Last year, at least seven water systems were found to be contaminated, suggesting drinking water contamination may be a more widespread problem than people realize.

Our new study[5] identifies critical issues that households and businesses should consider after a wildfire. Failing to address them can harm people’s health – mental, physical and financial.

Wildfires make drinking water unsafe

When wildfires damage[6] water distribution pipes, wells and the plumbing in homes and other buildings, they can create immediate health risks. A building’s plumbing can become contaminated by smoke getting sucked into water systems, by heat damaging plastic pipes[7] – or contamination penetrating into the plumbing and leaching out slowly over time.

Since 2017, multiple fires have rendered drinking water systems unsafe, including the[8] Echo[9] Mountain[10], Lionshead[11] and Almeda[12] fires in Oregon, and the CZU[13] Lightning[14] Complex[15], Camp[16] and Tubbs[17] fires in California. Thousands of private wells[18] have been affected too.

Being exposed to contaminated water can cause immediate harm, such as headaches, nausea, dizziness and vomiting. Short-term exposure to 26 parts per billion or more of benzene[19], a carcinogen, may cause a decrease in white blood cells that protect the body from infectious disease. Multiple fires have caused drinking water to exceed this level. A variety[20] of other chemicals can exceed safe drinking water exposure limits too in the absence of benzene.

Households are not being adequately warned

In a survey of 233 households[21] affected by water contamination, we found people reported high levels of anxiety and stress linked to the water problems. Nearly half had installed in-home water treatment because of uncertainty about the water. Eighty-five percent had looked for other water sources, such as bottled water.

In some cases, we found[22] that advice from government agencies placed households at greater risk of harm. It has sometimes left people exposed to chemicals, caused them to needlessly spend money and given them a false sense of security. Certified in-home water treatment devices, for example, are tested only to bring down 15 parts per billion of benzene to less than 5 parts per billion, the federal standard. These devices are not tested to treat hazardous waste-scale[23] contaminated water that’s been found after wildfires.

Following the 2020 CZU Lightning Complex Fire near Santa Cruz, California, a local health department correctly warned private well[24] owners not to use their water and to test it, but a nearby damaged water system and the state did not warn 17,000 people against bathing[25] in the contaminated water. It was only after test results proved the water had been unsafe all along that the system owner and state advised against bathing[26] in it.

In Oregon, some damaged systems encouraged people to boil[27] their drinking water, later finding that the water had benzene in it.

After the 2018 Camp Fire that devastated Paradise, California, the local health department correctly warned the entire county not to use or try to treat the drinking water[28], which had contamination above EPA’s hazardous waste limit. But one water system and the state encouraged 13,000 people to try to treat it themselves[29].

Pipes, water meters and meter covers after wildfires destroyed them.

Caitlin Proctor, Amisha Shah, David Yu, and Andrew Whelton/Purdue University, CC BY-ND[30][31]

Pipes, water meters and meter covers after wildfires destroyed them.

Caitlin Proctor, Amisha Shah, David Yu, and Andrew Whelton/Purdue University, CC BY-ND[30][31]

In all of these cases, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency chose not to compel water utilities to explicitly notify[32] customers about the water contamination and its risk.

Communities have received other bad information:

- Commercial labs[33] and government officials recommended flushing faucets for 5 to 15 minutes before collecting a water sample, thereby dumping out the contaminated plumbing water meant for testing.

- Homeowners were led[34] to believe a single cold water sample at the kitchen sink would determine if the hot water system and property service line was contaminated. It cannot.

- People were led[35] to believe that benzene water testing would determine if any other chemicals were present above safe limits. This is not possible.

What to look for after a nearby fire

Signs of potential contamination after a nearby wildfire could be loss of water pressure, discolored water, heat damage to water systems inside and outside buildings, and broken and leaking pipes, valves and hydrants.

Drinking water should be assumed to be chemically unsafe until proven otherwise.

Once a system is contaminated, cleanup can take months. The water system will have to be flushed and tested regularly to track down contamination[36]. Health departments should also issue guidance on how to test private wells and plumbing.

When testing plumbing, include the property service line as well as the hot and cold water lines. Before collecting a water sample, the water must sit long enough in the plumbing so contamination can be found – 72 hours was the Tubbs Fire and Camp Fire standard. Tests should look for more than benzene.

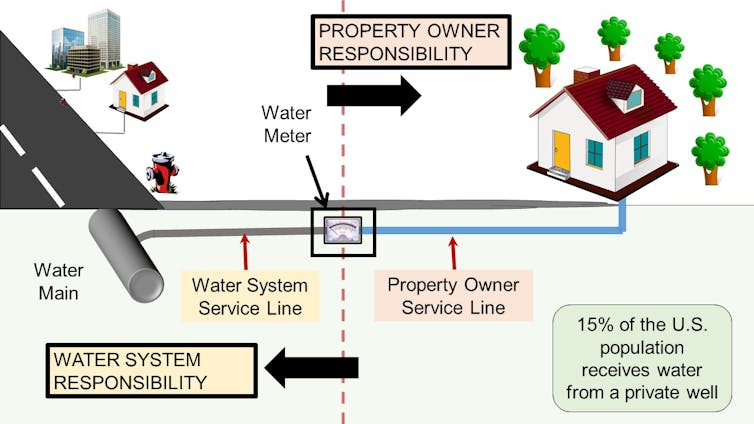

Building water systems can receive contaminated drinking water from public water systems and private wells.

Andrew Whelton/Purdue University, CC BY-ND[37]

Building water systems can receive contaminated drinking water from public water systems and private wells.

Andrew Whelton/Purdue University, CC BY-ND[37]

Who can help?

Many of the critical public health risks[38] identified in our new study can be addressed by public health departments with financial support from state and local agencies.

Public health departments often have experience responding to water problems, such as legionella outbreaks, and can provide technical advice about both chemical exposures, building plumbing and private drinking water wells.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[39].]

References

- ^ 58,000 (www.predictiveservices.nifc.gov)

- ^ drier (droughtmonitor.unl.edu)

- ^ plastic in water systems heats up (doi.org)

- ^ environmental engineer (engineering.purdue.edu)

- ^ new study (doi.org)

- ^ damage (doi.org)

- ^ plastic pipes (doi.org)

- ^ the (yourwater.oregon.gov)

- ^ Echo (yourwater.oregon.gov)

- ^ Mountain (yourwater.oregon.gov)

- ^ Lionshead (yourwater.oregon.gov)

- ^ Almeda (yourwater.oregon.gov)

- ^ CZU (www.slvwd.com)

- ^ Lightning (www.bigbasinwater.com)

- ^ Complex (www.countyofnapa.org)

- ^ Camp (doi.org)

- ^ Tubbs (doi.org)

- ^ wells (doi.org)

- ^ benzene (engineering.purdue.edu)

- ^ variety (doi.org)

- ^ survey of 233 households (doi.org)

- ^ we found (doi.org)

- ^ hazardous waste-scale (19january2017snapshot.epa.gov)

- ^ warned private well (www.santacruzcounty.us)

- ^ bathing (www.slvwd.com)

- ^ bathing (www.slvwd.com)

- ^ boil (www.cityoftalent.org)

- ^ treat the drinking water (buttecountyrecovers.org)

- ^ treat it themselves (www.waterboards.ca.gov)

- ^ Caitlin Proctor, Amisha Shah, David Yu, and Andrew Whelton/Purdue University (awwa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ notify (nepis.epa.gov)

- ^ labs (doi.org)

- ^ led (www.waterboards.ca.gov)

- ^ led (www.oregon.gov)

- ^ contamination (www.fema.gov)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ critical public health risks (doi.org)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Andrew J. Whelton, Associate Professor of Civil, Environmental & Ecological Engineering, Director of the Healthy Plumbing Consortium and Center for Plumbing Safety, Purdue University