Women of color spend more than $8 billion on bleaching creams worldwide every year

- Written by Ronald Hall, Professor of Social Work, Michigan State University

CC BY-ND[1]

The idealization of light skin as the pinnacle of beauty affects self-esteem[2] for women of color around the world. In many cultures, skin color is a social benchmark[3] that is often used by people of color and whites alike in lieu of race. Attractiveness, marriageability, career opportunities and socioeconomic status are directly correlated[4] with skin color.

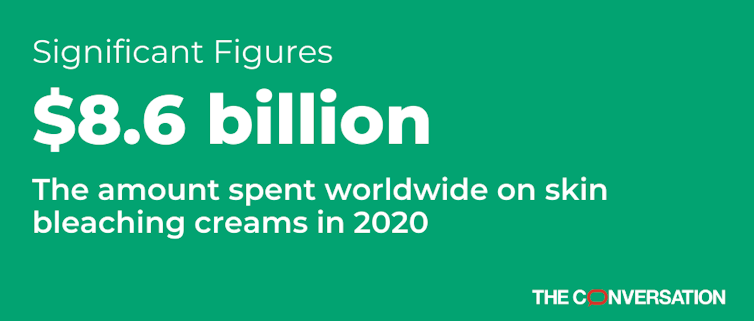

As a result, many women of color seek chemical remedies to lighten their complexion. They have created a booming global business in bleach creams and injectables[5] valued at US$8.6 billion[6] in 2020; $2.3 billion was spent in the U.S. alone. The market is projected to reach $12.3 billion by 2027.

In my work[7] in behavioral science and colorism, I studied the phenomenon of skin bleaching during a decade of travel around the world during which I visited every major racial group – and tracked the growth of this industry[8]. The practice has both significant racial implications and health concerns.

A new Netflix documentary called ‘Skin’ explores the practice of skin bleaching in African culture.A common practice

As I stated during my interview on Oprah’s 2015 “Light Girls” documentary, while bleaching the skin is common, it’s both dangerous and potentially life-threatening[9] because products contain steroids, hydroquinone bleach and mercury. The World Health Organization warns[10] that skin bleaching can cause liver and kidney damage, neurological problems, cancer and, for pregnant women, stillbirth.

The practice is not new. It became popular in many African countries[11] in the 1950s; today, about 77% of Nigerians, 27% of Senegalese and 35% of South African women bleach their skin. Indian caste-based discrimination was outlawed in 1950, but dark-skinned women (and men) are still persecuted[12] – and fair skin remains a distinguishing social factor, associated with purity and elite status.

In the Middle East, the practice of bleaching is most common in Jordan[13], with 60.7% of women bleaching. The Brazilian government seems to sanction white skin over dark by encouraging immigration from Europe and discouraging persons of African descent[14].

Light skin is idealized in North America, but the phenomenon is contentious because bleaching is perceived as a desire to be white. So bleaching creams are marketed in the U.S.[15] not to lighten skin, but to “erase blemishes” and “age spots.”

Their use in the U.S. spiked[16] after the 1967 U.S. Supreme Court ruling[17] that legalized interracial marriage.

In the aftermath of the civil rights movement, dark-complected immigrants from developing countries flocked to the U.S., carrying with them an ideal of light-skinned beauty – and they bleached their skin to attain it[18].

Ideals of light-skinned beauty stemming from European colonization contributed to a lucrative bleach cream industry.Perpetuating ‘colorism’

Bleach cream manufacturers now face growing pressure to address racism, with activists arguing that their products perpetuate a preference for lighter skin. In 2020, Johnson & Johnson announced that it will no longer sell[19] two products marketed to reduce dark spots that were widely used as skin lighteners.

L’Oreal, the world’s largest producer of bleach creams, pledged to remove[20] the words “white,” “fair,” and “light” from labels – but it will still manufacture these products.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[21].]

Some among African countries have moved to ban[22] bleaching creams. The success of the blockbuster film “Black Panther” has likewise sparked a movement celebrating dark skin, with hashtags including #melaninpoppin and #blackgirlmagic.

As I see it, public education and activism on this issue must prevail to protect the health and self-esteem of women of color. The failure of either will only prolong the problem – while sustaining an $8.6 billion bleach cream beauty industry.

CC BY-ND[1]

The idealization of light skin as the pinnacle of beauty affects self-esteem[2] for women of color around the world. In many cultures, skin color is a social benchmark[3] that is often used by people of color and whites alike in lieu of race. Attractiveness, marriageability, career opportunities and socioeconomic status are directly correlated[4] with skin color.

As a result, many women of color seek chemical remedies to lighten their complexion. They have created a booming global business in bleach creams and injectables[5] valued at US$8.6 billion[6] in 2020; $2.3 billion was spent in the U.S. alone. The market is projected to reach $12.3 billion by 2027.

In my work[7] in behavioral science and colorism, I studied the phenomenon of skin bleaching during a decade of travel around the world during which I visited every major racial group – and tracked the growth of this industry[8]. The practice has both significant racial implications and health concerns.

A new Netflix documentary called ‘Skin’ explores the practice of skin bleaching in African culture.A common practice

As I stated during my interview on Oprah’s 2015 “Light Girls” documentary, while bleaching the skin is common, it’s both dangerous and potentially life-threatening[9] because products contain steroids, hydroquinone bleach and mercury. The World Health Organization warns[10] that skin bleaching can cause liver and kidney damage, neurological problems, cancer and, for pregnant women, stillbirth.

The practice is not new. It became popular in many African countries[11] in the 1950s; today, about 77% of Nigerians, 27% of Senegalese and 35% of South African women bleach their skin. Indian caste-based discrimination was outlawed in 1950, but dark-skinned women (and men) are still persecuted[12] – and fair skin remains a distinguishing social factor, associated with purity and elite status.

In the Middle East, the practice of bleaching is most common in Jordan[13], with 60.7% of women bleaching. The Brazilian government seems to sanction white skin over dark by encouraging immigration from Europe and discouraging persons of African descent[14].

Light skin is idealized in North America, but the phenomenon is contentious because bleaching is perceived as a desire to be white. So bleaching creams are marketed in the U.S.[15] not to lighten skin, but to “erase blemishes” and “age spots.”

Their use in the U.S. spiked[16] after the 1967 U.S. Supreme Court ruling[17] that legalized interracial marriage.

In the aftermath of the civil rights movement, dark-complected immigrants from developing countries flocked to the U.S., carrying with them an ideal of light-skinned beauty – and they bleached their skin to attain it[18].

Ideals of light-skinned beauty stemming from European colonization contributed to a lucrative bleach cream industry.Perpetuating ‘colorism’

Bleach cream manufacturers now face growing pressure to address racism, with activists arguing that their products perpetuate a preference for lighter skin. In 2020, Johnson & Johnson announced that it will no longer sell[19] two products marketed to reduce dark spots that were widely used as skin lighteners.

L’Oreal, the world’s largest producer of bleach creams, pledged to remove[20] the words “white,” “fair,” and “light” from labels – but it will still manufacture these products.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[21].]

Some among African countries have moved to ban[22] bleaching creams. The success of the blockbuster film “Black Panther” has likewise sparked a movement celebrating dark skin, with hashtags including #melaninpoppin and #blackgirlmagic.

As I see it, public education and activism on this issue must prevail to protect the health and self-esteem of women of color. The failure of either will only prolong the problem – while sustaining an $8.6 billion bleach cream beauty industry.

References

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ affects self-esteem (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ social benchmark (doi.org)

- ^ correlated (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ injectables (www.un.org)

- ^ US$8.6 billion (www.strategyr.com)

- ^ work (scholar.google.com)

- ^ growth of this industry (theconversation.com)

- ^ dangerous and potentially life-threatening (tubitv.com)

- ^ warns (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ popular in many African countries (www.un.org)

- ^ persecuted (www.pri.org)

- ^ Jordan (doi.org)

- ^ immigration from Europe and discouraging persons of African descent (openscholarship.wustl.edu)

- ^ marketed in the U.S. (www.latimes.com)

- ^ use in the U.S. spiked (theconversation.com)

- ^ ruling (scholar.google.com)

- ^ bleached their skin to attain it (www.law.uci.edu)

- ^ no longer sell (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ remove (www.forbes.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ ban (www.voanews.com)

Authors: Ronald Hall, Professor of Social Work, Michigan State University