Why masks belong at your Thanksgiving gathering and how to properly clean and wear them

- Written by Jason Farley, Professor, Infectious Disease-Trained Epidemiologist and Nurse Practitioner, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing

COVID-19 has disrupted our daily lives, and it is poised to completely disrupt the holiday season. As people make holiday plans and think about ways to reduce the risks to their loved ones, a strategy is essential.

Face masks are a crucial part of that strategy, and they’re now mandatory in public in an increasing number of states[1] as COVID-19 cases soar[2].

I am an infectious disease-trained epidemiologist[3], researcher and nurse practitioner. Here are answers to some key questions about how and when to wear masks, and how to manage their use during the holidays.

Are masks really necessary at family gatherings?

If you’re gathering with friends and family who don’t live in your home, yes. Just because you’re with people you know doesn’t mean you’re safe from the coronavirus. Infection rates are higher now than they have ever been[4] in the U.S., and small gatherings have been a source[5] of viral spread. All it takes is one infected person who doesn’t know they have the coronavirus to infect others.

Remember, people can be contagious two to three days[6] before symptoms show – that’s one thing that makes this virus so hard to stop. And it’s why, even if you feel fine, you should wear a mask.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now estimates that when both people are wearing masks, the likelihood of infection is low[7].

Who am I protecting when I wear a mask?

In a word: everyone. The coronavirus spreads through respiratory droplets[8] that you send out into the air when you talk, sing or even just breathe. The tiniest of these droplets can float on air currents for long periods.

Face masks stop many of those droplets, reducing the amount of virus in the air. That lowers your chances of getting infected, and it also lowers the chances that you’ll infect someone else.

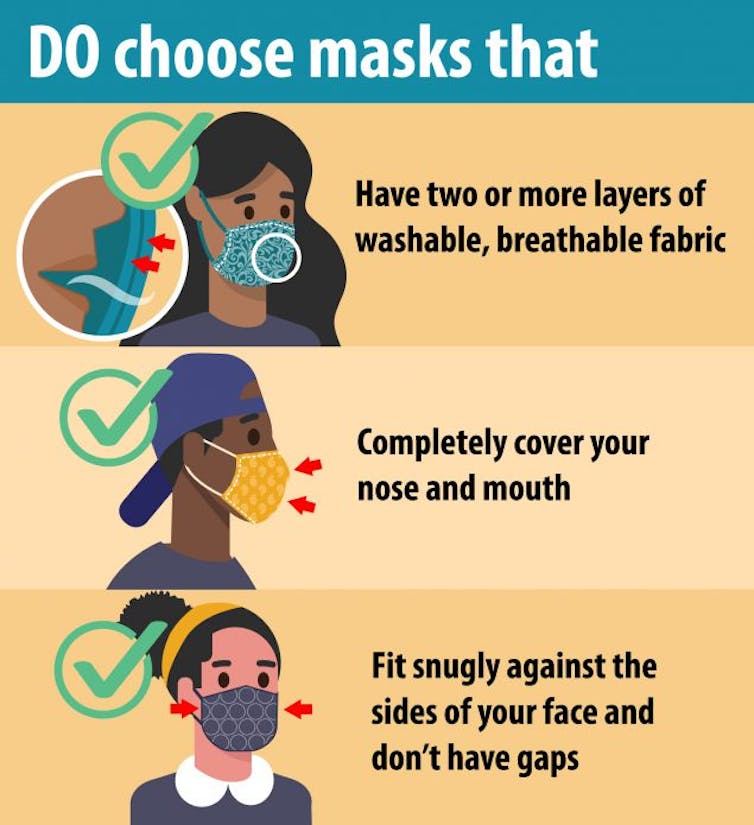

Studies of people who had prolonged exposure[9] to others with COVID-19 have demonstrated how masks can reduce the chance of the virus spreading. In general, well-fitted cloth masks[10] made up of multiple layers can stop most large droplets and at least half of the tiny ones. Plastic face shields[11] alone are far less effective. Face masks with valves or vents[12] might be good for construction work, but they don’t stop the wearer from breathing out virus into the air.

National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases[13]

Can I reuse a mask and when should I replace it?

Reusable masks should be kept clean and dry. We’re moving into cold and flu season, and noses get drippy. A rule of thumb: Anytime a mask is wet to the point that you can discern the wetness, it’s time for a new one if it’s disposable, or it’s time to clean your reusable mask.

Wetness allows viruses to more easily move through paper or fabric because it allows the threads to move and may reduce the electrostatic charge in the masks that add extra protection with some fabrics.

In general, you can use a mask that stays clean and dry for about a week before you need to wash or discard it.

How should I clean a cloth mask?

Washing your mask is like washing your clothes. You know when it is time.

In general, cleaning your mask weekly[14] should be sufficient. If odors develop before then, it’s a good idea to wash it sooner. Odor generally means bacterial buildup.

Cleaning your mask by hand with soap and water is your best option. Using a general detergent on a gentle cycle in the washing machine is also fine, but that may increase the risk of damage, depending on the quality of the material. COVID-19 is not a hardy virus. Any soap or detergent should work fine. There’s no need for special chemicals, bleach or harsh soaps.

Be careful to remove any inserts before washing. Inserted filters are generally not washable.

Air drying masks works best. Remember, masks should be completely dry before use. So be sure to have a replacement mask handy while the one you just washed dries.

Sunlight is always a great source of heat to dry your mask. Also, sunlight has ultraviolet radiation, which has been shown to eliminate coronavirus[15] and is also known to have antibacterial properties.

Can I wear the mask below my nose?

Wearing your mask below your nose is, frankly, ridiculous.

Think about it. If you are breathing through your nose and only covering your mouth, you are effectively eliminating the point of the mask. Properly wearing a mask requires covering both your nose and mouth at all times.

Studies show that wearing a proper cloth mask or surgical mask while exercising doesn’t affect the flow of oxygen[16] or carbon dioxide in any detectable way. So, unless you have serious heart and lung problems, that isn’t an excuse.

How do I safely remove my mask if I’m going to eat or drink?

When you take your mask off[17], remove it carefully by the straps without touching anything else and put it somewhere safe, like wrapped in paper in a purse, bag or pocket. Then wash your hands or use hand sanitizer. When you put it back on, wash your hands again.

National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases[13]

Can I reuse a mask and when should I replace it?

Reusable masks should be kept clean and dry. We’re moving into cold and flu season, and noses get drippy. A rule of thumb: Anytime a mask is wet to the point that you can discern the wetness, it’s time for a new one if it’s disposable, or it’s time to clean your reusable mask.

Wetness allows viruses to more easily move through paper or fabric because it allows the threads to move and may reduce the electrostatic charge in the masks that add extra protection with some fabrics.

In general, you can use a mask that stays clean and dry for about a week before you need to wash or discard it.

How should I clean a cloth mask?

Washing your mask is like washing your clothes. You know when it is time.

In general, cleaning your mask weekly[14] should be sufficient. If odors develop before then, it’s a good idea to wash it sooner. Odor generally means bacterial buildup.

Cleaning your mask by hand with soap and water is your best option. Using a general detergent on a gentle cycle in the washing machine is also fine, but that may increase the risk of damage, depending on the quality of the material. COVID-19 is not a hardy virus. Any soap or detergent should work fine. There’s no need for special chemicals, bleach or harsh soaps.

Be careful to remove any inserts before washing. Inserted filters are generally not washable.

Air drying masks works best. Remember, masks should be completely dry before use. So be sure to have a replacement mask handy while the one you just washed dries.

Sunlight is always a great source of heat to dry your mask. Also, sunlight has ultraviolet radiation, which has been shown to eliminate coronavirus[15] and is also known to have antibacterial properties.

Can I wear the mask below my nose?

Wearing your mask below your nose is, frankly, ridiculous.

Think about it. If you are breathing through your nose and only covering your mouth, you are effectively eliminating the point of the mask. Properly wearing a mask requires covering both your nose and mouth at all times.

Studies show that wearing a proper cloth mask or surgical mask while exercising doesn’t affect the flow of oxygen[16] or carbon dioxide in any detectable way. So, unless you have serious heart and lung problems, that isn’t an excuse.

How do I safely remove my mask if I’m going to eat or drink?

When you take your mask off[17], remove it carefully by the straps without touching anything else and put it somewhere safe, like wrapped in paper in a purse, bag or pocket. Then wash your hands or use hand sanitizer. When you put it back on, wash your hands again.

National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases[18]

So, how can I have a safe holiday gathering?

The safest way to celebrate this year is to do so with members only within your household. If you do celebrate with friends and relatives from outside your household, you need an action plan to reduce the risk of exposure.

Here are five recommendations:

Limit the number of people – fewer people means fewer opportunities for exposure, and you’ll have more room to spread out.

Require masks when not eating or drinking.

Use physical distancing when eating. Try to seat people at least 6 feet apart[19]. Eat outside if you can.

Consider being tested for COVID-19 before traveling or gathering. It’s not a guarantee, but it can help flag illnesses. Remember to self-isolate between the test and the event.

Be prepared to self-isolate for 14 days after traveling or participating in any event that involves people from outside your home.

[Research into coronavirus and other news from science Subscribe to The Conversation’s new science newsletter[20].]

National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases[18]

So, how can I have a safe holiday gathering?

The safest way to celebrate this year is to do so with members only within your household. If you do celebrate with friends and relatives from outside your household, you need an action plan to reduce the risk of exposure.

Here are five recommendations:

Limit the number of people – fewer people means fewer opportunities for exposure, and you’ll have more room to spread out.

Require masks when not eating or drinking.

Use physical distancing when eating. Try to seat people at least 6 feet apart[19]. Eat outside if you can.

Consider being tested for COVID-19 before traveling or gathering. It’s not a guarantee, but it can help flag illnesses. Remember to self-isolate between the test and the event.

Be prepared to self-isolate for 14 days after traveling or participating in any event that involves people from outside your home.

[Research into coronavirus and other news from science Subscribe to The Conversation’s new science newsletter[20].]

References

- ^ increasing number of states (www.kff.org)

- ^ cases soar (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ an infectious disease-trained epidemiologist (nursing.jhu.edu)

- ^ higher now than they have ever been (coronavirus.jhu.edu)

- ^ small gatherings have been a source (youtu.be)

- ^ contagious two to three days (medical.mit.edu)

- ^ likelihood of infection is low (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ spreads through respiratory droplets (theconversation.com)

- ^ Studies of people who had prolonged exposure (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ well-fitted cloth masks (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ face shields (doi.org)

- ^ Face masks with valves or vents (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ cleaning your mask weekly (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ eliminate coronavirus (doi.org)

- ^ doesn’t affect the flow of oxygen (doi.org)

- ^ take your mask off (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ at least 6 feet apart (doi.org)

- ^ Subscribe to The Conversation’s new science newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Jason Farley, Professor, Infectious Disease-Trained Epidemiologist and Nurse Practitioner, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing