In supporting same-sex civil unions, Pope Francis is showing how the Catholic definition of what constitutes a family is changing

- Written by Julie Hanlon Rubio, Professor of Christian Social Ethics, Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University

Pope Francis referred to gay people as “children of God” in a recently released documentary, “Francesco[1].” He further noted that “a civil union law” needs to be created so gays are “legally covered.” The Vatican later confirmed[2] the pope’s comments, but clarified that the church doctrine remained unchanged.

Public support for civil unions from Pope Francis is not entirely new. When he was archbishop of Buenos Aires[3], and again in a 2014 interview, he spoke about civil unions for same-sex couples.

While the Vatican is right in saying that church doctrine remains the same, as a theologian[4] who has been writing about Catholicism and family for over two decades, I see in the pope’s comments evidence that Catholic understanding of who counts as family is evolving.

From judgment to mercy

Traditional Catholic doctrine holds that marriage between a man and a woman is the foundation of the family. Sex outside of marriage is judged to be immoral and, while gay people are not seen as inherently sinful, their sexual actions are. Same-sex marriages and civil unions, the Vatican says, are harmful to society[5] and “in no way similar” to heterosexual marriages.

Yet in his comments made public on Oct. 21, the pope framed his support for civil unions in the context of family. “They’re children of God and have a right to a family. Nobody should be thrown out or be made miserable because of it,” he said in a news-breaking interview used in the documentary.

In researching for a book on Pope Francis[6], I found that he has consistently offered compassion for Catholics without traditional families. Soon after becoming pope in 2013, in response to a journalist’s question about a gay person, he famously said[7], “Who am I to judge?”

Mercy over judgment has been the mark of his papacy. The pope’s priority on extending mercy, theologian Cardinal Walter Kasper[8] explains[9], especially pertains to families.

Surveys commissioned by the Vatican in 2015 found that Catholics desire more acceptance from the church[10] for people who are single parents, divorced or have live-in relationships. Knowing that people often feel judged because their families aren’t perfect, Francis has tried to make them feel welcome[11]. He has stressed that the doors of churches must be open to all.

When, in discussing same-sex civil unions, Francis said that gay people have “a right to a family,” he seems to have implied that civil unions create a family. Though he is not changing Catholic moral teaching, I argue that he is departing from traditional Catholic rhetoric on the family and offering an inclusive, merciful vision to guide church practice.

From family structure to family action

Changes in Catholic teaching in the 20th century paved the way for Francis’ recent moves.

In a 1930 Vatican document on marriage[12], Pope Pius XI defended the traditional family structure against perceived threats of cohabitation, divorce and “false teachers” who asserted the equality of men and women.

Three decades later, at Vatican II, a meeting of the world’s bishops from 1962 to 1965 that led to sweeping reforms in the Catholic Church, emphasis shifted[13] to the role families could play in shaping society. Marriage was defined as an “intimate partnership of life and love,” and the family was praised as “a school of deeper humanity” where parents and children learn how to be better human beings.

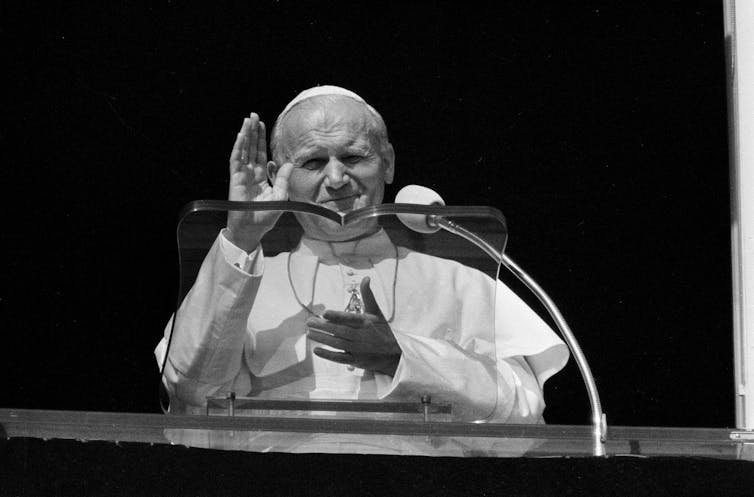

Pope John Paul II.

AP Photo[14]

Pope John Paul II.

AP Photo[14]

Pope John Paul II, who was pope from 1978 to 2005, is often viewed as a foil to Pope Francis. In his writings, he defended heterosexual marriage and traditional gender roles, as well as rules against divorce, contraception and same-sex relationships. Yet the former pope contributed to shifting the Catholic conversation to ethical actions families can take.

In this regard, John Paul II’s most important document on the family Familiaris Consortio, 1981[15], gave families four tasks: growing in love, raising children, contributing to society and praying in their home. He taught that being a family means engaging in actions related to these tasks.

Catholic scholars like Mary Doyle Roche[16] have since built on his framework to urge families to become “schools of solidarity[17]” in which parents and children learn compassion for others.

Though same-sex couples remain excluded from official Catholic teaching, Catholic theologians such as Margaret A. Farley[18] have suggested[19] that these families, too, could prioritize love, social action and spirituality. Gay couples, she argued, “deserve the same protection under the law” as heterosexual couples. They also have the same moral obligations to each other and to the common good.

Pope Francis on inclusion

Pope Francis built on work done at Vatican II and the decades following it. One of his favorite ways of describing the church is as a “field hospital[20]” that goes where people are hurting.

Though he has addressed many important social issues during his papacy, including economic inequality and climate change, he called the world’s bishops to special meetings in Rome only to discuss families[21]. He urged them to find creative ways of ministering to people who feel excluded because they are not living in line with Catholic doctrine on marriage.

Themes of welcome and inclusion for single parents, divorced and remarried people and cohabiting unmarried couples were amplified in the document Francis wrote in 2016, “Amoris Laetitia[22],” or “The Joy of Love.”

For instance, theologian Mary Catherine O'Reilly-Gindhart sees Francis saying that cohabiting unmarried couples[23] “need to be welcomed and guided patiently and discreetly.” This allows priests to meet couples where they are rather than shaming them or forcing them to hide their living situations.

What’s the future of the church?

Francis’ critics worry[24] that the pope is watering down Catholic doctrine on marriage and family. But what I argue is that Francis is not changing doctrine. He is encouraging a broader view of who counts as families inside and outside the church.

In the same documentary in which Francis made his remarks on same-sex civil unions, he also criticized countries[25] with overly restrictive immigration policies, saying, “It’s cruelty, and separating parents from kids goes against natural rights.” He was referring to the right to family[26], which “exists prior to the State or any other community.”

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[27].]

The comments in the documentary show a persistent move toward welcoming families in contemporary Catholic thought. Francis proposes that a welcoming church should support all families, especially those who are hurting. Similarly, as he says, governments should do the same – including supporting gay and lesbian couples.

References

- ^ Francesco (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Vatican later confirmed (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ archbishop of Buenos Aires (www.ncronline.org)

- ^ theologian (press.georgetown.edu)

- ^ are harmful to society (www.vatican.va)

- ^ researching for a book on Pope Francis (litpress.org)

- ^ he famously said (www.ncronline.org)

- ^ Walter Kasper (www.bc.edu)

- ^ explains (www.commonwealmagazine.org)

- ^ Catholics desire more acceptance from the church (www.pewforum.org)

- ^ feel welcome (www.vatican.va)

- ^ 1930 Vatican document on marriage (www.vatican.va)

- ^ emphasis shifted (ecommons.udayton.edu)

- ^ AP Photo (newsroom.ap.org)

- ^ Familiaris Consortio, 1981 (www.vatican.va)

- ^ Mary Doyle Roche (www.holycross.edu)

- ^ schools of solidarity (litpress.org)

- ^ Margaret A. Farley (divinity.yale.edu)

- ^ suggested (www.bloomsbury.com)

- ^ field hospital (www.eerdmans.com)

- ^ only to discuss families (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ Amoris Laetitia (www.vatican.va)

- ^ saying that cohabiting unmarried couples (ixtheo.de)

- ^ Francis’ critics worry (www.ignatius.com)

- ^ he also criticized countries (www.americamagazine.org)

- ^ right to family (www.vatican.va)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Julie Hanlon Rubio, Professor of Christian Social Ethics, Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University