Cigarette smoke can reprogram cells in your airways, causing COPD to hang on after smoking ends

- Written by Bradley Richmond, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Vanderbilt University

Smoking is the most common cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, an often fatal respiratory condition that afflicts millions[1] of Americans. But for many patients living with COPD, stopping smoking isn’t the end of the battle.

Cigarette smoke is a complex mixture of gases, chemicals and even bacteria. When it enters the lungs, it generates an inflammatory response much like pneumonia.

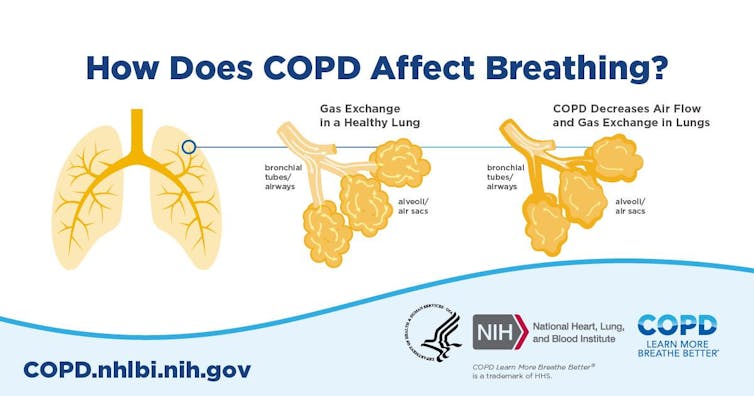

Inflammatory cells normally clear from the lungs when an infection ends or a patient quits smoking, but in patients with COPD, these cells may persist for years. Destructive enzymes produced by these cells – intended to destroy bacteria – cause progressive lung damage and respiratory failure characteristic of COPD.

It’s been a mystery why these cells continue triggering inflammation in the lungs after people stop smoking. Now, new research indicates[2] a defect in the immune system induced by cigarette smoke is to blame. Cigarette smoke reprograms the cells lining the airways[3], making the lungs of COPD patients who have quit smoking more susceptible to bacterial invasion.

Good fences make good neighbors

The lungs are continuously bombarded by inhaled bacteria and other irritants. At the same time, they are tasked with getting oxygen into the bloodstream, so they can’t have an impermeable physical barrier like skin.

To solve this dilemma, the lungs have developed a multi-pronged defense system. A key component of this system is an antibody called secretory IgA. These antibodies latch on to bacteria to prevent them from invading the lungs. Secretory IgA doesn’t directly kill microbes, but it prevents them from triggering a damaging immune response before they can be cleared by other mechanisms.

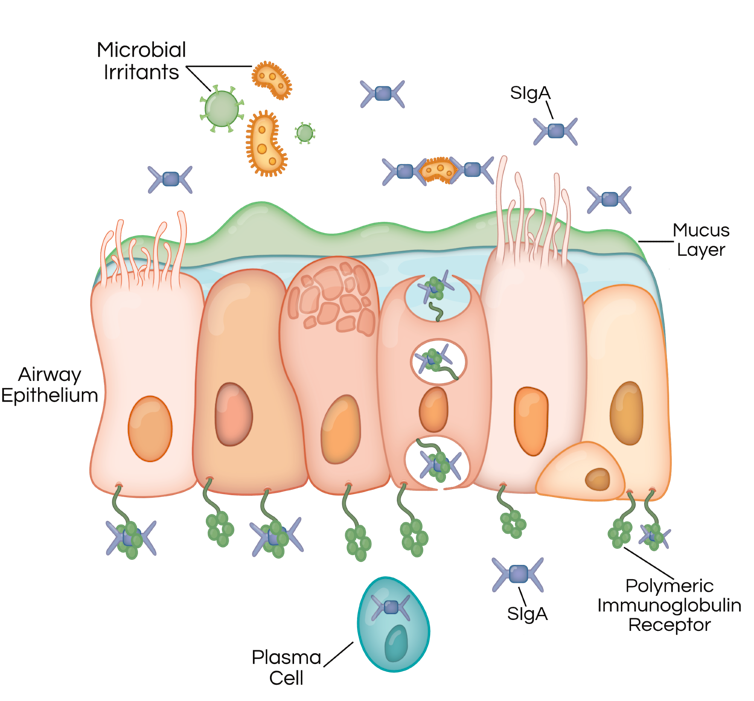

Our airways are lined with a layer of cells called the airway epithelium. When bacteria and other germs are inhaled, one way the airway epithelium protects itself is by transporting secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA) to the airway surface. SIgA attaches to bacteria to prevent them from invading and causing inflammation. SIgA is made by plasma cells beneath the airway epithelium and transported by polymeric immunoglobulin receptors. People with COPD lack SIgA in their airways, which allows bacterial invasion, inflammation and lung damage.

Dayana Espinoza/Vanderbilt University, CC BY-ND[4]

Our airways are lined with a layer of cells called the airway epithelium. When bacteria and other germs are inhaled, one way the airway epithelium protects itself is by transporting secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA) to the airway surface. SIgA attaches to bacteria to prevent them from invading and causing inflammation. SIgA is made by plasma cells beneath the airway epithelium and transported by polymeric immunoglobulin receptors. People with COPD lack SIgA in their airways, which allows bacterial invasion, inflammation and lung damage.

Dayana Espinoza/Vanderbilt University, CC BY-ND[4]

In patients with COPD, lower levels of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor[5] and secretory IgA allow bacteria easier access to the airway surface[6], triggering an inflammatory response[7] that persists after the patient quits smoking.

Mice that have been genetically manipulated to lack secretory IgA also develop inflammation and a pattern of lung damage[8] resembling patients with COPD. Antibiotics can prevent them from developing lung disease, suggesting bacteria cause continued inflammation after smoking ends.

The double-edged sword of anti-inflammatories

Since inflammation is central to COPD, it makes sense that anti-inflammatory therapies might be beneficial. However, patients with COPD are also susceptible to lung infections, and anti-inflammatories run the risk of deactivating the body’s natural defenses against infection. The threat is more than theoretical: A clinical trial[9] studying an anti-inflammatory drug called rituximab was stopped early due to an increased rate of pulmonary infections.

Many antibiotics also have serious side effects when taken chronically, and prolonged use might encourage growth of bacteria resistant to these drugs.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute[10]

A new target for treating COPD?

While studying mice lacking secretory IgA, our research team at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and colleagues at the University of Florida recently found these mice have increased numbers of a relatively uncommon type of cell called monocyte-derived dendritic cells, or moDCs, in the lungs.

Dendritic cells don’t directly destroy bacteria, but they ring the alarm that a bacterial infection is brewing and coordinate the subsequent immune response. Unlike typical dendritic cells, moDCs begin their lives as a different cell type, called a monocyte. But when chronic inflammation sets in, they can become a type of dendritic cell.

We showed that in mice genetically engineered to lack secretory IgA, moDCs activate T lymphocytes[11] – white blood cells that fight off viruses and can destroy cells in the process – and those T lymphocytes in turn damage the lungs. These data implied that moDCs might also coordinate a pathologic immune response in patients with COPD who also lack secretory IgA in the airways.

Because moDCs weren’t known to exist in human lungs, we used a cutting-edge technique called mass cytometry[12] to detect them. It allows us to distinguish moDCs from other cell types that appear very similar under a microscope.

Like secretory IgA-deficient mice, we found that human COPD patients lacking secretory IgA had increased numbers of moDCs in their lungs. Together, these data suggest that loss of secretory IgA makes the airways more susceptible to bacterial invasion, which activates moDCs to drive ongoing lung inflammation. Therefore, targeting moDCs through medical treatments might block inflammation and lung damage in patients with COPD.

New drugs are urgently needed for COPD

There are still many questions to answer, including how best to target moDCs. It also remains to be seen whether such a strategy would compromise the ability of COPD patients to defend against infection.

However, for a disease as common and debilitating as COPD, potential new drug targets come as a breath of fresh air.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[13].]

COPD is the fourth leading cause of death in the U.S.[14] and the third leading cause of death worldwide[15]. While many drugs are available to decrease symptoms and hospitalization rates in patients with COPD, none has been proven to prolong life.

Most patients with COPD don’t die from it, but those who live with COPD[16] suffer from chronic breathlessness which negatively impacts their quality of life. The burden of COPD is felt not just by individual patients, but by families, workplaces and economies.

Though cigarette smoking rates are declining in the United States[17], they are increasing in many other countries[18], making COPD a global health issue.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute[10]

A new target for treating COPD?

While studying mice lacking secretory IgA, our research team at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and colleagues at the University of Florida recently found these mice have increased numbers of a relatively uncommon type of cell called monocyte-derived dendritic cells, or moDCs, in the lungs.

Dendritic cells don’t directly destroy bacteria, but they ring the alarm that a bacterial infection is brewing and coordinate the subsequent immune response. Unlike typical dendritic cells, moDCs begin their lives as a different cell type, called a monocyte. But when chronic inflammation sets in, they can become a type of dendritic cell.

We showed that in mice genetically engineered to lack secretory IgA, moDCs activate T lymphocytes[11] – white blood cells that fight off viruses and can destroy cells in the process – and those T lymphocytes in turn damage the lungs. These data implied that moDCs might also coordinate a pathologic immune response in patients with COPD who also lack secretory IgA in the airways.

Because moDCs weren’t known to exist in human lungs, we used a cutting-edge technique called mass cytometry[12] to detect them. It allows us to distinguish moDCs from other cell types that appear very similar under a microscope.

Like secretory IgA-deficient mice, we found that human COPD patients lacking secretory IgA had increased numbers of moDCs in their lungs. Together, these data suggest that loss of secretory IgA makes the airways more susceptible to bacterial invasion, which activates moDCs to drive ongoing lung inflammation. Therefore, targeting moDCs through medical treatments might block inflammation and lung damage in patients with COPD.

New drugs are urgently needed for COPD

There are still many questions to answer, including how best to target moDCs. It also remains to be seen whether such a strategy would compromise the ability of COPD patients to defend against infection.

However, for a disease as common and debilitating as COPD, potential new drug targets come as a breath of fresh air.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[13].]

COPD is the fourth leading cause of death in the U.S.[14] and the third leading cause of death worldwide[15]. While many drugs are available to decrease symptoms and hospitalization rates in patients with COPD, none has been proven to prolong life.

Most patients with COPD don’t die from it, but those who live with COPD[16] suffer from chronic breathlessness which negatively impacts their quality of life. The burden of COPD is felt not just by individual patients, but by families, workplaces and economies.

Though cigarette smoking rates are declining in the United States[17], they are increasing in many other countries[18], making COPD a global health issue.

References

- ^ afflicts millions (www.lung.org)

- ^ research indicates (www.vumc.org)

- ^ reprograms the cells lining the airways (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ allow bacteria easier access to the airway surface (doi.org)

- ^ an inflammatory response (doi.org)

- ^ also develop inflammation and a pattern of lung damage (doi.org)

- ^ clinical trial (doi.org)

- ^ National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (www.nhlbi.nih.gov)

- ^ moDCs activate T lymphocytes (doi.org)

- ^ used a cutting-edge technique called mass cytometry (doi.org)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ fourth leading cause of death in the U.S. (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ third leading cause of death worldwide (www.who.int)

- ^ but those who live with COPD (www.lung.org)

- ^ declining in the United States (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ increasing in many other countries (www.who.int)

Authors: Bradley Richmond, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Vanderbilt University