What's the best way to get out the vote in a pandemic?

- Written by Lisa García Bedolla, Vice Provost for Graduate Studies and Dean of the Graduate Division, Professor of Education, University of California, Berkeley

Identifying supporters and getting them to the polls are key parts of any political campaign. The pandemic, however, creates new challenges for candidates trying to convey their messages and mobilize voters.

Decades of political science research[1] have made clear that mobilizing in person, either on the doorstep or on the phone, is the most effective way of moving voters to the polls. A well-run door-to-door campaign can be expected to increase turnout by 7 to 9 percentage points[2]; an effective phone campaign can be expected to lead to a 3% to 5% increase in voter turnout.

However, even before the pandemic, it was getting harder and harder to reach voters in person or on the phone. When I began studying voter mobilization in 2005, it was common for door-to-door get-out-the-vote efforts to reach half of the people they tried to contact.

By the 2018 election, I found that few of the organizations I worked with reliably reached more than 15% of the people they hoped to connect with. It is getting more and more difficult to get voters to open the door to a stranger or answer a call from a number they do not recognize.

A shift from away from personal connection

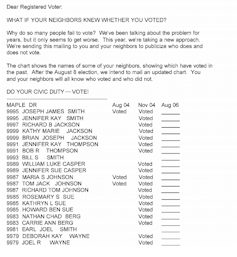

Mailings reporting whether you and your neighbors vote can boost election turnout.

Gerber, Green, Larimer (2008).[3]

Mailings reporting whether you and your neighbors vote can boost election turnout.

Gerber, Green, Larimer (2008).[3]

That is part of the reason why over the past few election cycles, campaigns have shifted to other forms of contact, including mail and texting. The type of mailing that gets the most people to the polls[4] threatens to tell recipients’ neighbors whether or not they voted[5]. They use phrases like “After the election[6] … you and your neighbors will all know who voted and who did not.” That type of message can increase turnout by as much as 3 percentage points.

Texting is similarly effective. A reminder text has been shown to increase turnout[7] among habitual voters by about 3 percentage points. Campaigns have developed texting systems that let volunteers reach broader audiences more easily than traditional texting. Canvassers send texts directly and recipients can reply, interacting with the canvasser via text in real time.

Studies suggest this form of text outreach can have an even greater impact on turnout[8] among those who choose to engage with a canvasser. Yet, as these outreach methods have become less novel, response rates have plummeted[9], creating the same challenges we see with in-person methods in terms of being able to have direct contact with voters.

Even before the pandemic hit, candidates and campaigns were struggling to find ways to reach voters. The pandemic has only made it more difficult.

Amid a pandemic, door-to-door campaigning is dropping off.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images[10]

Amid a pandemic, door-to-door campaigning is dropping off.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images[10]

Getting friends and neighbors involved

In response, campaigns are moving toward asking people to contact people they know to garner support and turn those supporters out. Organizations like Michelle Obama’s When We All Vote[11] ask people to commit to turning out three to five of their friends. These friend-to-friend approaches are seen as a way to cut through the noise, allowing voters to be contacted by people they trust and who will know whether or not they follow through on their commitments.

It’s not yet clear how effective they will be, but these network-based approaches are expected to succeed for the same reasons why scholars believe social pressure works: They create a sense of accountability among voters, knowing that someone is paying attention to whether or not they vote. They also build on people’s existing political discussion networks[12], which are key to voter engagement.

However, strategies and tactics that work on regular voters may not be as effective for people who are less likely to vote. About 40% of eligible voters[13] in the United States did not vote in the 2016 election. So it is important that campaigns and organizations mobilizing voters make sure their outreach strategies are effective for previous nonvoters as well.

The pandemic has fostered a flurry of new tools and devices designed to turn out voters, such as Outvote[14] and Outreach Circle[15]. Among other things, these platforms allow people to upload their contacts and commit to contacting individuals with whom they already have a connection. The likely lesson from these efforts will be that the most effective messengers are people’s close friends and family.

References

- ^ political science research (www.brookings.edu)

- ^ 7 to 9 percentage points (www.brookings.edu)

- ^ Gerber, Green, Larimer (2008). (doi.org)

- ^ gets the most people to the polls (dx.doi.org)

- ^ tell recipients’ neighbors whether or not they voted (doi.org)

- ^ After the election (doi.org)

- ^ increase turnout (lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu)

- ^ even greater impact on turnout (lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu)

- ^ response rates have plummeted (medium.com)

- ^ Joe Raedle/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ When We All Vote (www.whenweallvote.org)

- ^ political discussion networks (global.oup.com)

- ^ 40% of eligible voters (www.electproject.org)

- ^ Outvote (www.outvote.io)

- ^ Outreach Circle (blog.outreachcircle.com)

Authors: Lisa García Bedolla, Vice Provost for Graduate Studies and Dean of the Graduate Division, Professor of Education, University of California, Berkeley

Read more https://theconversation.com/whats-the-best-way-to-get-out-the-vote-in-a-pandemic-146523