3 ways a 6-3 Supreme Court would be different

- Written by Morgan Marietta, Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Massachusetts Lowell

If the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is replaced this year, the Supreme Court will become something the country has not seen since the justices became a dominant force in American cultural life after World War II: a decidedly conservative court.

A court with a 6-3 conservative majority would be a dramatic shift from the court of recent years, which was more closely divided, with Ginsburg as the leader of the liberal wing of four justices and Chief Justice John Roberts as the frequent swing vote.

As a scholar of the court[1] and the politics of belief[2], I see three things likely to change in an era of a conservative majority: The court will accept a broader range of controversial cases for consideration; the court’s interpretation of constitutional rights will shift; and the future of rights in the era of a conservative court may be in the hands of local democracy rather than the Supreme Court.

A broader docket

The court takes only cases the justices choose to hear. Five votes on the nine-member court make a majority, but four is the number required to take a case[3].

If Roberts does not want to accept a controversial case, it now requires all four of the conservatives – Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Clarence Thomas – to accept the case and risk the outcome.

If they are uncertain how Roberts will rule – as many people are[4] – then the conservatives may be not be willing to grant a hearing.

With six conservatives on the court, that would change. More certain of the outcome, the court would likely take up a broader range of divisive cases. These include many gun regulations[5] that have been challenged as a violation of the Second Amendment, and the brewing conflicts[6] between gay rights and religious rights[7] that the court has so far sidestepped[8]. They also include new abortion regulations[9] that states will implement in anticipation of legal challenges and a favorable hearing at the court.

The three liberal justices would no longer be able to insist that a case be heard without participation from at least one of the six conservatives, effectively limiting many controversies from consideration at the high court.

The seat formerly occupied by the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg is draped in black, as is the bench in front of her.

Fred Schilling/Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States via AP[10]

The seat formerly occupied by the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg is draped in black, as is the bench in front of her.

Fred Schilling/Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States via AP[10]

A rights reformation

The rise of a 6-3 conservative court would also mean the end of the expansion of rights the court has overseen during the past half-century.

Conservatives believe constitutional rights such as freedom of religion and speech, bearing arms, and limits on police searches are immutable. But they question the expansive claims of rights that have emerged over time, such as privacy rights and reproductive liberty. These also include LGBTQ rights[11], voting rights[12], health care rights[13], and any other rights not specifically protected in the text of the Constitution.

The court has grounded several expanded rights, especially the right to privacy, in the 14th Amendment’s due process clause[14]: “…nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” This sounds like a matter of procedure: The government has to apply the same laws to everyone without arbitrary actions. From the conservative perspective, courts have expanded the meaning of “due process” and “liberty” far beyond their legitimate borders[15], taking decision-making away from democratic majorities.

Consequently, LGBTQ rights will not expand further. The line of decisions[16] that made Justice Anthony Kennedy famous for his support of gay rights, culminating in marriage equality in 2015[17], will advance no further.

Cases that seek to outlaw capital punishment under the Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishments[18]” will also cease to be successful. In 2019 the court ruled that excessive pain caused by a rare medical condition[19] was not grounds for halting a death sentence. That execution went forward, and further claims against the constitutionality of the death penalty will not.

Challenges to voting restrictions will likely also fail. This was previewed in the 5-4 decision in 2018[20] allowing Ohio to purge voting rolls of infrequent voters. The Bill of Rights does not protect voting as a clear right[21], leaving voting regulations to state legislatures. The conservative court will likely allow a broader range of restrictive election regulations, including barring felons from voting[22]. It may also limit the census enumeration to citizens, effectively reducing the congressional power of states that have large noncitizen immigrant populations[23].

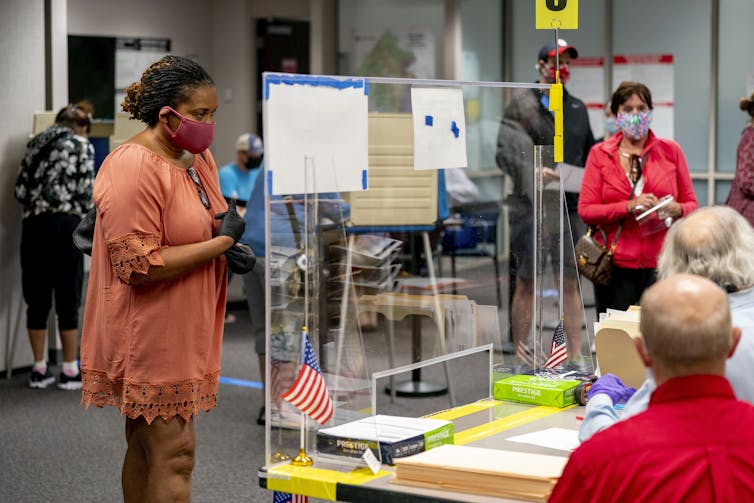

Early voting in the November election has already begun; voting rights may be restricted by a more conservative Supreme Court.

AP Photo/Andrew Harnik[24]

Early voting in the November election has already begun; voting rights may be restricted by a more conservative Supreme Court.

AP Photo/Andrew Harnik[24]

Birthright citizenship[25], which many believe is protected by the 14th Amendment, will likely not be formally recognized by the court. The court has never ruled that anyone born on U.S. soil is automatically a citizen[26]. The closest it came was an 1898 ruling recognizing the citizenship of children of legal residents[27], but the court has been silent on the divisive question of children born of unauthorized residents.

The conservative understanding of the 14th Amendment[28] is that it had no intention of granting birthright citizenship to those who are in the country without legal authorization[29].

Noncitizens may also find themselves with fewer rights: Many conservatives argue that the 14th Amendment[30] requires state governments to abide by the Bill of Rights[31] only when dealing with U.S. citizens[32].

In any case, individual rights will likely be less important than the government’s efforts to protect national security – whether fighting terrorism, conducting surveillance or dealing with emergencies. Conservatives argue that the public need for security often trumps private claims of rights. This was previewed in Trump v. Hawaii[33] in 2018, when the court upheld the travel ban imposed against several Muslim countries.

Not all rights will be restricted. Those protected by the original Bill of Rights will gain greater protections under a conservative court. Most notably this includes gun rights under the Second Amendment, and religious rights under the First Amendment[34].

Until recently, the court had viewed religious rights primarily through the establishment clause[35]’s limits on government endorsement of religion. But in the past decade, that has shifted in favor of the free exercise clause[36]’s ban on interference with the practice of religion.

The court has upheld claims to religious rights in education[37] and religious exceptions to anti-discrimination laws[38]. That trend will continue.

Baker Jack Phillips, owner of Masterpiece Cakeshop, manages his Colorado business after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that he could refuse to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple because of his religious beliefs.

AP Photo/David Zalubowski[39]

Baker Jack Phillips, owner of Masterpiece Cakeshop, manages his Colorado business after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that he could refuse to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple because of his religious beliefs.

AP Photo/David Zalubowski[39]

A return to local democracy

Perhaps the most important ramification of a 6-3 conservative court is that it will return many policies to local control.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[40].]

For example, overturning Roe v. Wade – which is likely but not certain under a 6-3 court – would leave the legality of abortion up to each state.

This will make state-level elected officials the guardians of individual liberties, shifting power from courts to elections. How citizens and their elected officials respond to this new emphasis is perhaps the most important thing that will determine the influence of a conservative court.

References

- ^ scholar of the court (www.palgrave.com)

- ^ politics of belief (global.oup.com)

- ^ four is the number required to take a case (www.uscourts.gov)

- ^ as many people are (www.idahostatejournal.com)

- ^ gun regulations (www.cnbc.com)

- ^ brewing conflicts (firstliberty.org)

- ^ religious rights (theconversation.com)

- ^ has so far sidestepped (www.scotusblog.com)

- ^ new abortion regulations (www.americanprogress.org)

- ^ Fred Schilling/Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States via AP (newsroom.ap.org)

- ^ LGBTQ rights (www.scotusblog.com)

- ^ voting rights (www.scotusblog.com)

- ^ health care rights (www.scotusblog.com)

- ^ due process clause (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ far beyond their legitimate borders (billofrightsinstitute.org)

- ^ line of decisions (www.oyez.org)

- ^ culminating in marriage equality in 2015 (www.oyez.org)

- ^ cruel and unusual punishments (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ excessive pain caused by a rare medical condition (www.scotusblog.com)

- ^ 5-4 decision in 2018 (www.scotusblog.com)

- ^ does not protect voting as a clear right (theconversation.com)

- ^ barring felons from voting (theconversation.com)

- ^ reducing the congressional power of states that have large noncitizen immigrant populations (www.whitehouse.gov)

- ^ AP Photo/Andrew Harnik (newsroom.ap.org)

- ^ Birthright citizenship (theconversation.com)

- ^ automatically a citizen (constitutioncenter.org)

- ^ recognizing the citizenship of children of legal residents (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ conservative understanding of the 14th Amendment (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ without legal authorization (fedsoc.org)

- ^ 14th Amendment (law.justia.com)

- ^ state governments to abide by the Bill of Rights (constitutioncenter.org)

- ^ U.S. citizens (archive.thinkprogress.org)

- ^ Trump v. Hawaii (www.scotusblog.com)

- ^ religious rights under the First Amendment (theconversation.com)

- ^ establishment clause (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ free exercise clause (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ religious rights in education (www.scotusblog.com)

- ^ religious exceptions to anti-discrimination laws (www.scotusblog.com)

- ^ AP Photo/David Zalubowski (newsroom.ap.org)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Morgan Marietta, Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Massachusetts Lowell

Read more https://theconversation.com/3-ways-a-6-3-supreme-court-would-be-different-146558