Defending the 2020 election against hacking: 5 questions answered

- Written by Douglas W. Jones, Associate Professor of Computer Science, University of Iowa

Editor’s note: Journalist Bob Woodward reports in his new book, “Rage[1],” that the NSA and CIA have classified evidence that the Russian intelligence services placed malware in the election registration systems[2] of at least two Florida counties in 2016, and that the malware was sophisticated and could erase voters. This appears to confirm earlier reports[3]. Meanwhile, Russian intelligence agents and other foreign players are already at work interfering in the 2020 presidential election[4]. Douglas W. Jones, Associate Professor of Computer Science at the University of Iowa and coauthor of the book “Broken Ballots: Will Your Vote Count?[5],” describes the vulnerabilities of the U.S. election system in light of this news.

1. Though Woodward reports there was no evidence the election registration system malware had been activated, this sounds scary. Should people be worried?

Yes, we should be worried. Four years ago, Russia managed to penetrate systems in several states but there’s no evidence that they “pulled the trigger” to take advantage of their penetration. One possibility is that they simply saw no need, having successfully “hacked the electorate” by damaging Hillary Clinton’s candidacy through selective dumps of hacked documents on Wikileaks[6].

We know that VR Systems, a contractor that worked for several Florida counties, was hacked[7], and we know that there were serious problems in Durham County, North Carolina,[8] during the 2016 election, including software glitches that caused poll workers to turn away voters during parts of Election Day. Durham county was also a VR Systems customer[9].

I know of no post-election investigation of the problems in Durham County that was conducted with sufficient depth to assure me that Russia was not involved. It remains possible that they did pull the trigger on that county, but it is also possible that the problems there were entirely the result of “normal incompetence.”

2. How does this change what we knew previously about Russian efforts to hack U.S. election systems?

The specific counties compromised in Florida were never officially revealed. Previous leaks indicated that Washington County was one of them. Now we know that St. Lucie was the other.

Furthermore, previous reports mostly said that the systems had been penetrated. Woodward is saying that malware was installed on these machines. I am not sure whether I should interpret his use of terms in their narrow technical sense, but there is a significant difference between penetration, as in “they got the password to your system, broke in and looked around,” and installing malware, as in “they got in and made technical changes to the operation of your system.”

The latter is far more serious because voters could have been removed from registration rolls and therefore prevented from casting ballots, and that’s what I gather Woodward is describing.

3. How have attempts to hack U.S. election systems changed since 2016?

I do not have inside knowledge of what’s going on now, but my impression is that the Russians are getting more subtle. The basic Russian tactics of four years ago were only moderately subtle. Dumping all the stolen Democratic National Committee files on Wikileaks wasn’t subtle, but some of the narrowcasting of targeted misinformation on social media[10] was brilliant, if utterly evil. For example, using Facebook, Russian propagandists were able to target prospective voters in swing states[11] with disinformation tailored for them.

My impression is that they’re getting better at disinformation campaigns. I think it’s safe to assume that they’re also getting better at digging into the actual machinery of elections.

4. Have efforts to defend U.S. election systems against hackers improved?

On the social media front, there has certainly been improvement. The obvious “sock puppet farms[12],” large numbers of fake accounts controlled by a single entity, that Russia was running on U.S. social media are far more difficult to run these days because of the way the social media companies are cracking down. What I fear is that the country is defending against the attacks of four years ago while not really knowing about the attacks of today.

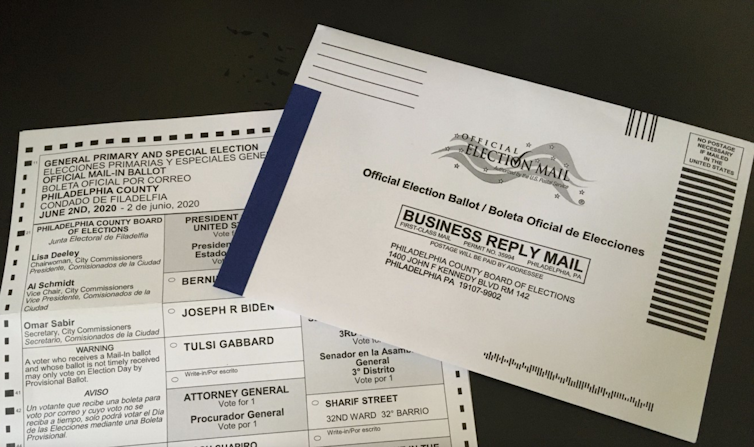

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to lead to a large increase in mail-in ballots like this 2020 primary election ballot in Philadelphia.

WCN 24/7/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND[13][14]

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to lead to a large increase in mail-in ballots like this 2020 primary election ballot in Philadelphia.

WCN 24/7/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND[13][14]

In the world of actual election machinery, the U.S. has made a little progress, but COVID-19 has thrown a monkey wrench in the system, forcing a massive shift to postal ballots[15] in states that permit this. That means that attacks on polling-place machinery will be generally less effective than in the past, while attacks on county election offices remain a real threat.

5. What keeps you awake at night going into the 2020 presidential election?

Oh dear. The list is long. Everything from crazies on the loony fringe of American politics shooting at each other in response to election results they don’t like, to people living in such closed media bubbles that we are effectively two different cultures living next door to each other while believing entirely different things about the world we live in.

Between those extremes, consider the possibility of results appearing to be reversed after polls have closed. If there is a demographic split between the vote-in-person crowd and the vote-by-mail crowd, election night results could go one way, while in states like Iowa, where postal ballots received six days after the election get counted[16] if there is proof they were mailed on time, the final results could go another way.

Then, add in the possibility of hacked central tabulating software in key counties, and there’s plenty to lose sleep over.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter[17].]

References

- ^ Rage (www.simonandschuster.com)

- ^ Russian intelligence services placed malware in the election registration systems (www.cnn.com)

- ^ earlier reports (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ interfering in the 2020 presidential election (www.technologyreview.com)

- ^ Broken Ballots: Will Your Vote Count? (press.uchicago.edu)

- ^ selective dumps of hacked documents on Wikileaks (www.reuters.com)

- ^ was hacked (www.politico.com)

- ^ serious problems in Durham County, North Carolina, (www.newsobserver.com)

- ^ a VR Systems customer (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ targeted misinformation on social media (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ target prospective voters in swing states (www.wired.com)

- ^ sock puppet farms (theconversation.com)

- ^ WCN 24/7/Flickr (www.flickr.com)

- ^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ forcing a massive shift to postal ballots (theconversation.com)

- ^ ballots received six days after the election get counted (sos.iowa.gov)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Douglas W. Jones, Associate Professor of Computer Science, University of Iowa

Read more https://theconversation.com/defending-the-2020-election-against-hacking-5-questions-answered-146055