More dengue fever and less malaria – mosquito control strategies may need to shift as Africa heats up

- Written by Jason Rasgon, Professor of Entomology and Disease Epidemiology, Pennsylvania State University

As it becomes too warm for comfort, the Anopheles mosquitoes[1] that transmit malaria may lose the battle against climate change in Africa. But a new foe is on the horizon.

When temperatures are too hot for malaria parasites and the Anopheles mosquitoes that transmit them, conditions may be just right for a different mosquito called Aedes aegypti[2] to thrive. This new mosquito brings the threat of many viruses that it carries.

I have been working[3] on vector-borne diseases, including malaria and multiple arthropod-borne viral diseases, for over 20 years. A new paper by Erin Mordecai and colleagues[4] published in Lancet Planetary Health presents an intriguing look into the future where hot temperatures caused by global warming make much of Africa inhospitable for malaria but other mosquito-borne diseases become widespread.

Too hot for one mosquito; just right for another

The new study suggests that climate change may lead to reductions in malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. Malaria[5] is one of the major killers in Africa, with more than 200 million cases and 400,000 deaths[6] every year. The parasites, and the Anopheles mosquitoes that transmit them, are widespread across sub-Saharan Africa. However, malaria is not the only vector-borne disease to be concerned about in Africa. Arthropod-borne viruses – or arboviruses – are also widespread on the continent.

Anopheles mosquitoes themselves are known to transmit a few viruses – including Mayaro virus[7] and O'nyong nyong virus[8]. But the most important viral vector is the mosquito Aedes aegypti, which transmits many different viruses including dengue virus, the most widespread[9] mosquito-borne virus on the planet.

Aedes aegypti and dengue virus (and other viruses) are widespread across Africa. But they are underreported and underrecognized[10] as public health threats because most surveillance is focused on malaria. Furthermore, some viral symptoms of dengue can mimic malaria infection[11].

Aedes mosquitoes and arboviruses do better in hotter environments compared to Anopheles mosquitoes and malaria parasites. And as environmental conditions become warmer over the next 60 years, malaria may wane but viral pathogens such as dengue fever, with its associated rash, fever, body aches and potentially more severe life-threatening hemorrhagic and shock symptoms, will likely rise, the new study concludes.

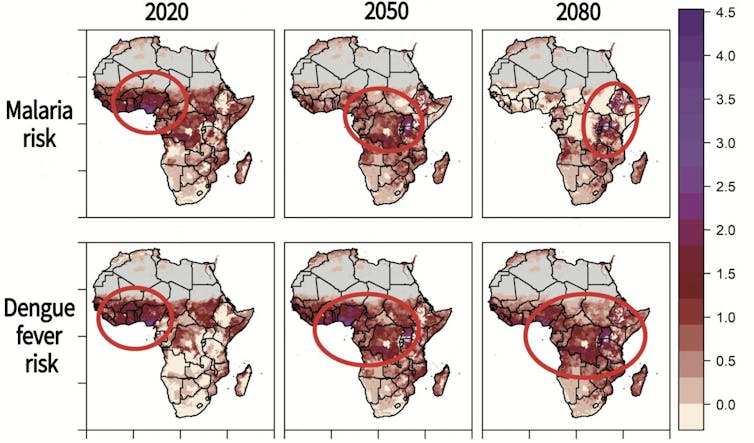

Possible scenarios of temperature-driven changes in disease risk across sub-Saharan Africa under a business-as-usual climate scenario. Red circles denote disease risk hot spots. Color scale indicates the intensity of human exposure risk, based on temperature.

Mordecai, et al. / Lancet Planetary Health, CC BY-SA[12]

Possible scenarios of temperature-driven changes in disease risk across sub-Saharan Africa under a business-as-usual climate scenario. Red circles denote disease risk hot spots. Color scale indicates the intensity of human exposure risk, based on temperature.

Mordecai, et al. / Lancet Planetary Health, CC BY-SA[12]

New diseases on the rise

Vector control efforts that work for night-biting, indoor-feeding Anopheles mosquitoes – such as insecticide-treated bednets and insecticides – do not work for outdoor-feeding, day-biting Aedes mosquitoes. And, unlike malaria, there are no drugs or therapeutic treatments for dengue or other viral pathogens.

If public health strategies are not adapted to the new climate reality, outbreaks of dengue and other viruses are expected to replace the disappearing malaria epidemics we see today, according to this new research paper.

Mordecai and colleagues[13] used data from multiple sources to develop and validate models of malaria and dengue transmission potential. They showed that while malaria transmission does best at approximately 25 degrees Celsius, dengue transmission was more efficient at a much warmer 29°C.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[14].]

As climate change makes much of Africa hotter in the coming century, the authors predict that by 2080 malaria cases will be significantly reduced as Anopheles retreat to cooler areas. Dengue, on the other hand, will be widespread as climate and urbanization create more widespread habitat for Aedes mosquitoes.

As Aedes aegypti is already present in sub-Saharan Africa and viral pathogens such as dengue virus are present, Mordecai and colleagues make the compelling argument that public health efforts should consider monitoring and controlling arboviruses as an emerging problem as malaria recedes.

Indeed, their results suggest that widespread arbovirus transmission may already be occurring, but not fully recognized, right under our noses.

References

- ^ Anopheles mosquitoes (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ Aedes aegypti (www.who.int)

- ^ I have been working (rasgonlab.com)

- ^ Erin Mordecai and colleagues (www.thelancet.com)

- ^ Malaria (www.niaid.nih.gov)

- ^ 200 million cases and 400,000 deaths (www.who.int)

- ^ Mayaro virus (journals.plos.org)

- ^ O'nyong nyong virus (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ widespread (www.nature.com)

- ^ underreported and underrecognized (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ viral symptoms of dengue can mimic malaria infection (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Mordecai and colleagues (www.thelancet.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Jason Rasgon, Professor of Entomology and Disease Epidemiology, Pennsylvania State University