Would America vote for Oprah for president?

- Written by Chryl N. Laird, Assistant Professor of Government and Legal Studies, Bowdoin College

America has had a black president.

Is the country ready for a black president who is also a woman?

Speculation about the candidacy of Oprah Winfrey makes clear that some voters think so. Granted, Winfrey says she won’t run[1], but friends[2], commentators[3] and many in the Twitterverse[4] are pushing for her to reconsider.

As a scholar of race and politics[5], I’m curious about whether Oprah will change her mind about running – and even more curious about whether she could win.

Occupying a unique space

A paper I recently published[6] with Harwood McClerking[7] and Ray Block[8] tried to shed light on this question by examining Oprah’s first major foray into politics — her endorsement of Democratic candidate Barack Obama during the 2008 presidential election. Specifically, we wanted to know how the endorsement altered the public’s perception of her, as a way of understanding if people like the idea of a “political Oprah.”

First, it helps to understand just how popular Oprah was leading up to the 2008 election. From 2002 to 2006, Winfrey’s daytime talk show pulled in an estimated 7 million viewers[9] every day. Winfrey also had racial crossover appeal, maintaining an audience that was predominately female, white and over the age of 55[10].

During this phase of her career, Oprah avoided politics, a strategy that may have helped her “transcend her race,” to borrow a phrase from political scientists Donald Kinder and Corrine McConnaughy[11].

For example, in an interview with the Jacksonville Daily News in 1986[12], Oprah described her high school experience: “Everyone went through the black-power phase … (but) I knew I was not a dashiki kind of girl.”

Talking to People Weekly a year later[13], Oprah said that during college at Tennessee State, a historically black college, she “refused to conform to the militant thinking of the time.”

“People feel you have to lead a civil rights movement every day of your life, that you have to be a spokeswoman and represent the race,” Oprah said. “Blackness is something I just am.”

Writing in 1994, media scholar Janice Peck[14] asserted that Winfrey served “as a comforting, nonthreatening bridge between black and white culture.” She goes on to say that Winfrey minimized her race through “public rejection of black political activism and the Civil Rights Movement.”

Winfrey’s Obama endorsement

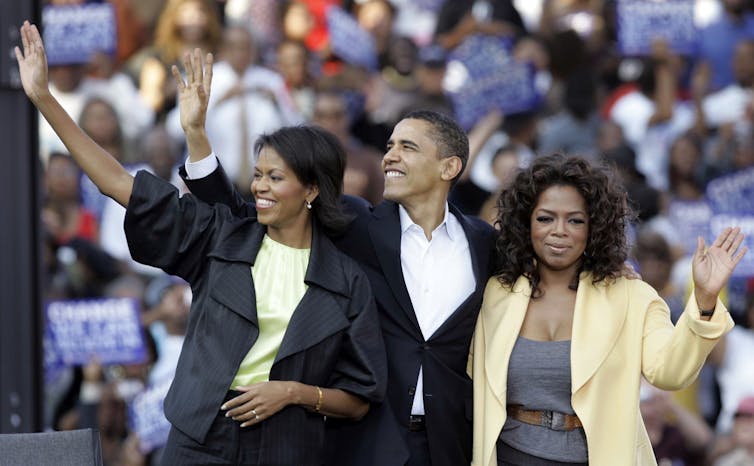

Michelle and Barack Obama campaign with Oprah Winfrey in 2008.

AP Photo/Mary Ann Chastain

Michelle and Barack Obama campaign with Oprah Winfrey in 2008.

AP Photo/Mary Ann Chastain

This notion of Winfrey’s racial transcendence was tested in May 2007 with her explicit endorsement of Obama, which made her racial identity and political views salient to the American people. This connection was not lost on viewers, some of whom said she was trying to “sway her mass following[15].”

Politics scholar Costas Panagopoulos[16] predicted that the endorsement would cause Winfrey’s popularity to suffer. It didn’t help that Winfrey’s endorsement of Obama alienated her from white women – the largest segment of her audience – who believed that, as a woman, she should have backed Hillary Clinton.

Winfrey and black women’s consciousness

Oprah isn’t the first black woman to struggle with two minority identities.

Gender studies scholars[17] find that historically, black women reside in a unique space where they are marginalized by black communities due to their gender and sidelined by the feminist movement due to their race.

Claudine Gay and Katherine Tate[18] assert in their research that the experience of being “doubly bounded” has resulted in the formation of a black female consciousness. Gender and legal scholar Kimberle Crenshaw[19] argues that the experiences faced by black women cannot be understood through traditional understanding of race and gender discrimination. Crenshaw believes that the intersection of racism and sexism interact in a way resulting in shared experience with discrimination that is more severe for black women. To describe this situation, Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality.”

The fragility of racial transcendence

To understand Winfrey’s transcendence and its fragility, we used Harris Polls’[20] measure of how Winfrey ranked relative to other television personalities regularly during a large span of her talk show, from 1993 to 2011. In the years leading up to her Obama endorsement – 2002 to 2006 – she was the nation’s favorite television personality. But immediately following her endorsement, her favorability dropped to No. 4. Over the next five years until her show ended in 2011, Oprah’s average ranking was No. 3.

Before her endorsement of Obama, individuals were favorable toward Winfrey at relatively equal levels – between 73 and 82 percent – regardless of their race and gender. After the endorsement, a gap opened up. Black women rated her 86.2 percent favorable. Black men still maintain the second highest favorability, but we see a drop from 81 percent to 72 percent. Similarly, the percentage of white women who hold favorable ratings of Winfrey drops from 73.4 percent pre-endorsement to 67.8 percent after.

By examining post-endorsement polling data, we argue that the impact of Oprah’s endorsement is an important factor that seems to follow the same breakdown. Her endorsement had the strongest tangible effect on black women, followed by black men, white women and white men.

These numbers are important when considering Oprah’s electability because blacks make up only 11.9 percent of the electorate[21]. Having black support alone is not enough to win the presidency. Indeed, Obama built his success on support beyond the black community[22] by having high levels of turnout from voters under the age of 30, low- to moderate-income workers – those earning less than $50,000 – and Latinos.

Oprah 2020?

Despite the seeming impact on her popularity, Winfrey has become more political over time.

For instance, in a recent series of articles in Oprah Magazine and on Oprah.com[23], Winfrey discusses race[24] and racial awareness[25] in a very different way than those interviews from the 80s.

In one article[26], she writes, “The audacity it takes to judge another because they don’t look or sound or act like you goes against the current of humanity.” In another[27]: “We can’t afford to say race is just a black thing, or a Hispanic thing, or an Asian thing or a #StayWoke thing. It’s a human thing.”

The speculation centered on Winfrey’s possible presidential bid – while encouraging on its own – lacks a full assessment of all that Winfrey brings to the table. The experiences of black women, even those that are high-profile, are often constrained by how people view them.

Oprah’s claim that “time’s up” inspired many, but our research suggests that the more political Oprah becomes, the more aware voters will be of her race and gender. And that awareness will give her not one, but two, challenges to overcome.

References

- ^ Winfrey says she won’t run (www.cnn.com)

- ^ friends (www.eonline.com)

- ^ commentators (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ many in the Twitterverse (twitter.com)

- ^ a scholar of race and politics (scholar.google.com)

- ^ I recently published (doi.org)

- ^ Harwood McClerking (uwm.edu)

- ^ Ray Block (polisci.as.uky.edu)

- ^ an estimated 7 million viewers (mediadecoder.blogs.nytimes.com)

- ^ predominately female, white and over the age of 55 (www.huffingtonpost.com)

- ^ political scientists Donald Kinder and Corrine McConnaughy (www.jstor.org)

- ^ Jacksonville Daily News in 1986 (books.google.com)

- ^ People Weekly a year later (people.com)

- ^ media scholar Janice Peck (www.jstor.org)

- ^ “sway her mass following (articles.chicagotribune.com)

- ^ Politics scholar Costas Panagopoulos (www.politico.com)

- ^ Gender studies scholars (www.jstor.org)

- ^ Claudine Gay and Katherine Tate (www.jstor.org)

- ^ Kimberle Crenshaw (www.jstor.org)

- ^ Harris Polls’ (www.harrispollonline.com)

- ^ 11.9 percent of the electorate (www.pewresearch.org)

- ^ support beyond the black community (www.pewresearch.org)

- ^ Oprah.com (www.oprah.com)

- ^ race (www.oprah.com)

- ^ racial awareness (www.oprah.com)

- ^ one article (www.oprah.com)

- ^ In another (www.oprah.com)

Authors: Chryl N. Laird, Assistant Professor of Government and Legal Studies, Bowdoin College

Read more http://theconversation.com/would-america-vote-for-oprah-for-president-91999