Want to know how many people have the coronavirus? Test randomly

- Written by Daniel N. Rockmore, William H. Neukom 1964 Distinguished Professor of Computational Science, Associate Dean for the Sciences, Dartmouth College, Dartmouth College

Consider these two questions: What percentage of Americans are, or have been, infected with the coronavirus? And, what is the probability of dying from the virus if you catch it? One of the most unsettling aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic is that these two fundamental rates – the coronavirus infection rate and the case fatality rate – are not known[1].

As a political scientist[2] and an applied mathematician[3], we are frequently asked to find rates of beliefs or opinions within larger groups. The same approaches we use for political polling can be used to answer how widespread and how deadly the coronavirus is.

Given infinite resources, the simplest way to find out how many Americans have the virus and what risk it poses would be to test every person in the United States. But there are not infinite resources, and testing for the coronavirus has been much more selective[4]. As of April 8, the CDC’s top priorities for testing are hospitalized patients and medical staff with symptoms[5], and overall it is generally symptomatic people who have been tested.

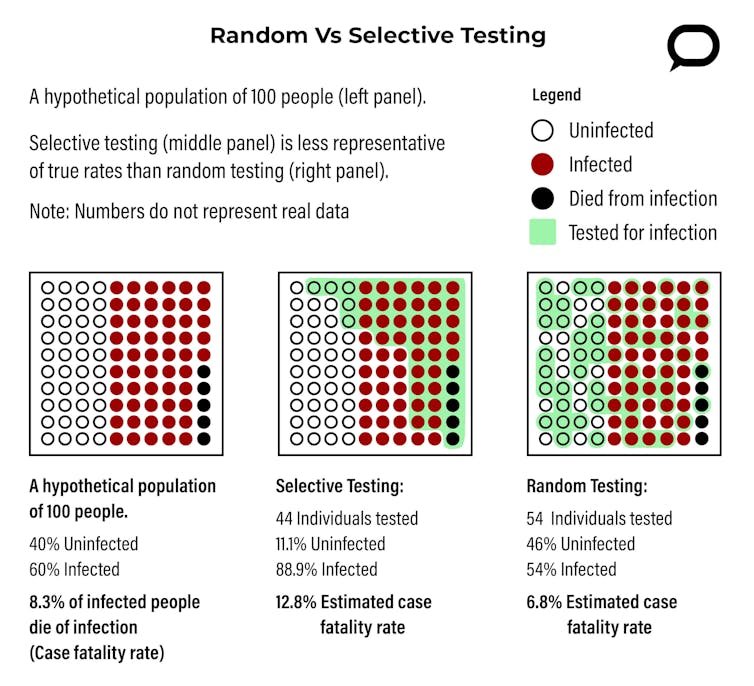

Because of this selective testing, epidemiologists and public health officials in the U.S. simply do not know the true extent of the coronavirus’s penetration into the country – that is, the virus’s infection rate. And without knowing how many people have been infected, the case fatality rate – the probability of dying from the virus if you catch it – and many other statistics associated with the coronavirus are impossible to calculate. Fortunately, there is a straightforward way to learn how widespread and deadly COVID-19 really is: Test randomly.

Testing the sick and symptomatic

So why isn’t it possible to calculate the coronavirus’s infection and case fatality rates from the millions of COVID-19 tests that have already been performed[6] in the United States? The problem lies not in the number of tests but rather in who has been tested.

Testing symptomatic patients reflects a classic error in sampling. Researchers want to know who has coronavirus, but since most of those tested have symptoms, medical professionals have been sampling from a group with higher rates of infection than you’d expect in the population as a whole. People with symptoms of COVID-19 are more likely to have COVID-19 than a person chosen at random.

People who go for voluntary testing are more likely to be sick than a person chosen at random.

AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki[7]

People who go for voluntary testing are more likely to be sick than a person chosen at random.

AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki[7]

The reasons for this selective testing are completely understandable. When testing is a scarce resource, people with COVID-19 symptoms should get tested so that proper treatments can be offered and contact tracing can begin[8]. Additionally, time and numbers of health workers are both limited, and it is convenient to test people who show up at hospitals and doctor’s offices requesting to be tested. But people who show up at health facilities are more likely to be symptomatic and have COVID-19 in the first place.

The people tested for the coronavirus are not a good representation of the U.S. population at large. Therefore, the rate of infection and case fatality rate in this group do not represent the larger U.S. population.

Random testing is representative testing

The ability to test the entire population for the coronavirus may be a long way off[9], but it isn’t necessary to test everyone in the U.S. to get accurate numbers. By testing a large enough number of people randomly, it is possible to get a sample group whose demographics are representative of the whole country. This is exactly how surveys and polls are done.

Public health officials could start randomly picking people from across the United States, testing them for the presence of the coronavirus, and then following up to see what fraction of those who tested positive for the coronavirus died from COVID-19. If random testing is done right, the infection and case fatality rates in the random sample should be very close to the actual rates in the whole U.S. population.

The Conversation U.S., CC BY-ND[10]

So how many people do you need to randomly test to get data that can accurately describe the whole U.S.? Fortunately, the mathematics behind this question have long been worked out, and the number is probably smaller than you might think.

Presidential approval polls often sample roughly 1,000 people[11]. This produces a margin of error of approximately 3%, meaning that random chance could make the results off by up to 3%.

A margin of error of 3% may be fine for estimating presidential approval, but it is probably not accurate enough for the coronavirus pandemic. If 10,000 individuals in the U.S. were tested for the virus, the margin of error for the virus’s infection rate becomes 1%. In practice, these margins of error are conservative. Actual margins of error from a random sample of 10,000 individuals will probably be much smaller and likely accurate enough to start giving public health officials useful information about the total number of infected and case fatality rates for those who have the coronavirus.

Ten thousand may seem large, but as of April 8 the United States has already tested more than 2 million people[12]. The key is in random selection. A sample of 10,000 Americans is most useful if those being tested are chosen by lottery.

The Conversation U.S., CC BY-ND[10]

So how many people do you need to randomly test to get data that can accurately describe the whole U.S.? Fortunately, the mathematics behind this question have long been worked out, and the number is probably smaller than you might think.

Presidential approval polls often sample roughly 1,000 people[11]. This produces a margin of error of approximately 3%, meaning that random chance could make the results off by up to 3%.

A margin of error of 3% may be fine for estimating presidential approval, but it is probably not accurate enough for the coronavirus pandemic. If 10,000 individuals in the U.S. were tested for the virus, the margin of error for the virus’s infection rate becomes 1%. In practice, these margins of error are conservative. Actual margins of error from a random sample of 10,000 individuals will probably be much smaller and likely accurate enough to start giving public health officials useful information about the total number of infected and case fatality rates for those who have the coronavirus.

Ten thousand may seem large, but as of April 8 the United States has already tested more than 2 million people[12]. The key is in random selection. A sample of 10,000 Americans is most useful if those being tested are chosen by lottery.

With good information about geographic and demographic distribution of the virus, aid can be redirected to areas that need it most.

AP Photo/Elaine Thompson[13]

Why these statistics matter

With a national random sample, epidemiologists would be able to learn much more than just the total number of coronavirus cases and the virus’s case fatality rate in the U.S. People who are infected but not sick would be tested and the rate of asymptomatic cases could be determined.

This sample would also provide information with respect to geography, ethnicity and other demographic variables. There is already some data showing that certain demographics - namely African Americans[14] and lower-income individuals[15] – are disproportionately affected by the virus. This suggests that the rates of infection of COVID-19 and its case fatality rate vary across different regions of the U.S. and across different subgroups of the country’s population. Random sampling could illuminate trends like these before the worst damage is done, and public health officials could enact targeted and nuanced policies to help high-risk groups or regions.

While random testing has not been part of the national discussion of the coronavirus, this may be changing. On April 4, Ohio Department of Health Director Amy Acton announced that her state is working with the CDC to develop a random sampling plan[16]. The goal of this project is to determine the true extent of the coronavirus in Ohio[17] without testing the whole state.

Public health officials have used randomization in other settings, such as monitoring the spread of typhoid fever in parts of Egypt[18], and it works. The mathematics behind random sampling is foundational to many areas of polling and statistics. The only thing public health officials need to do is figure out the execution. Random testing is certainly possible in the U.S. and would provide valuable information to the public health officials who are fighting the coronavirus crisis.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter[19].]

With good information about geographic and demographic distribution of the virus, aid can be redirected to areas that need it most.

AP Photo/Elaine Thompson[13]

Why these statistics matter

With a national random sample, epidemiologists would be able to learn much more than just the total number of coronavirus cases and the virus’s case fatality rate in the U.S. People who are infected but not sick would be tested and the rate of asymptomatic cases could be determined.

This sample would also provide information with respect to geography, ethnicity and other demographic variables. There is already some data showing that certain demographics - namely African Americans[14] and lower-income individuals[15] – are disproportionately affected by the virus. This suggests that the rates of infection of COVID-19 and its case fatality rate vary across different regions of the U.S. and across different subgroups of the country’s population. Random sampling could illuminate trends like these before the worst damage is done, and public health officials could enact targeted and nuanced policies to help high-risk groups or regions.

While random testing has not been part of the national discussion of the coronavirus, this may be changing. On April 4, Ohio Department of Health Director Amy Acton announced that her state is working with the CDC to develop a random sampling plan[16]. The goal of this project is to determine the true extent of the coronavirus in Ohio[17] without testing the whole state.

Public health officials have used randomization in other settings, such as monitoring the spread of typhoid fever in parts of Egypt[18], and it works. The mathematics behind random sampling is foundational to many areas of polling and statistics. The only thing public health officials need to do is figure out the execution. Random testing is certainly possible in the U.S. and would provide valuable information to the public health officials who are fighting the coronavirus crisis.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter[19].]

References

- ^ these two fundamental rates – the coronavirus infection rate and the case fatality rate – are not known (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ political scientist (scholar.google.co.uk)

- ^ applied mathematician (faculty-directory.dartmouth.edu)

- ^ been much more selective (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ hospitalized patients and medical staff with symptoms (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ millions of COVID-19 tests that have already been performed (covidtracking.com)

- ^ AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki (www.apimages.com)

- ^ proper treatments can be offered and contact tracing can begin (www.heart.org)

- ^ may be a long way off (www.newyorker.com)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ sample roughly 1,000 people (projects.fivethirtyeight.com)

- ^ already tested more than 2 million people (covidtracking.com)

- ^ AP Photo/Elaine Thompson (www.apimages.com)

- ^ African Americans (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ lower-income individuals (time.com)

- ^ develop a random sampling plan (www.news5cleveland.com)

- ^ extent of the coronavirus in Ohio (www.cleveland.com)

- ^ typhoid fever in parts of Egypt (dx.doi.org)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Daniel N. Rockmore, William H. Neukom 1964 Distinguished Professor of Computational Science, Associate Dean for the Sciences, Dartmouth College, Dartmouth College

Read more https://theconversation.com/want-to-know-how-many-people-have-the-coronavirus-test-randomly-135784