Lithium ion Nobel Prize shows how individual brainstorms add up to world-transforming innovations

- Written by Amy Prieto, Professor of Chemistry, Colorado State University

Nobel Prizes in Chemistry seem to rotate between novel compounds, revolutionary measurement techniques, and insights into how atoms can be combined to form new molecules and solids. This year, however, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry[1] was awarded to the inventors of a device that has revolutionized how people use energy on demand – the ubiquitous lithium-ion rechargeable battery.

The greatest challenge to creating this device was developing its three main components[2] – the cathode, the electrode that stores lithium ions when the battery is discharged (when it’s run out of capacity, and your device tells you your battery is low); the anode, the electrode that stores the lithium atoms when the battery is charged; and the electrolyte, which is the liquid in between the two electrodes that allows the lithium ions to pass between them. Lithium ions are lithium atoms that have given up one electron.

Once these components are assembled into a battery they immediately start interacting with each other. These interactions are often the reason your battery fails or doesn’t last as long as you would like.

I am a solid state electrochemist[3] who works on rechargeable batteries. I was particularly thrilled to learn of this prize because I spend my time thinking about how to assemble the three components of lithium ion rechargeable batteries in new ways to get even better performance out of them. The three winners of the Chemistry Nobel this year started an enormous field of research that people like me are very excited about contributing to.

How battery innovation progressed

A battery’s two electrodes are meant to shuttle lithium ions between them. When your battery is fully charged, lithium atoms are stored in the anode – that’s pretty high energy. Then, when you use your battery to do work, electrons flow through your device creating the current you are using to do work; the lithium ions flow from the anode to the cathode.

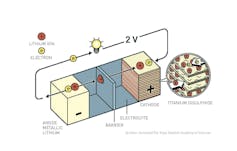

M. Stanley Whittingham[4], one of three recipients of the Chemistry prize, demonstrated the first rechargeable lithium battery, using a compound called titanium disulfide (which is basically a clay) as the cathode. This material lets lithium ions hang out between the layers of titanium and sulfur atoms, like a Chantilly cake, while they wait to get charged up again.

The basics of how Wittingham’s first lithium battery worked.

© Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, CC BY-NC[5][6]

The basics of how Wittingham’s first lithium battery worked.

© Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, CC BY-NC[5][6]

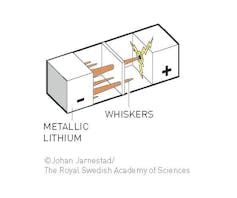

The problem with using lithium metal as the anode.

© Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, CC BY-NC[7][8]

The problem with using lithium metal as the anode.

© Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, CC BY-NC[7][8]

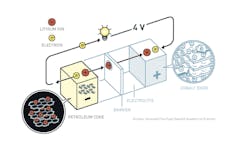

The fundamentals of the modern lithium ion battery.

© Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, CC BY-NC[9][10]

The fundamentals of the modern lithium ion battery.

© Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, CC BY-NC[9][10]

John B. Goodenough[11], the second winner, built a better cake using a really simple, elegant understanding of how different atoms on the periodic table like to bond together. He used cobalt oxide as the cathode and nearly doubled the amount of energy that the battery can store.

Both Whittingham and Goodenough used elegant applications of the kind of chemistry professors like me teach to first-year undergraduates. However both of their batteries were limited by the lithium metal anode, which gets rough over time and grows bristles of lithium metal on the surface that look like the branches of a pine tree. This is a big problem that leads to shorts and can cause the battery to catch on fire after multiple recharges.

Akira Yoshino’s[12] key insight was to store the lithium atoms between layers of graphite in the anode, thereby solving the roughening problem. The innovations built off each other like a zig zag ladder.

The power of synergistic collaboration

There is a key lesson from the success of this device that battery developers must communicate more broadly. Translating the battery design that the three men ultimately came up with - LiCoO2 as the cathode, graphite as the anode – to the massive manufacturing scale that exists today required innovation, ambition and years of patience.

While each of the winners worked on a different component of this device, they all recognized that it’s the interactions between components that create the greatest challenges.

The areas researchers need to improve now are how to store even more energy in a single battery so that our cell phones last longer and we can drive electric cars further. Scientists and engineers also need to develop batteries that charge and release energy very quickly on demand, how to make batteries last longer, and how to make them safe.

Solving the next big challenges in energy storage will require discovering new materials for each component of the battery. We need anodes and cathodes that store lots of lithium, or even better, elements that can donate two or more electrons per atom, instead of just one, so that we can double or triple the amount of energy a battery can store. Batteries would also benefit from more stable electrolytes that are not flammable. Finally, all these components need to be combined into functioning devices.

Although the current lithium ion battery is a great device that certainly makes life easier, there are areas of significant possible improvement to enable better portable devices, better cars and better grid-scale renewable energy storage.

The boundaries of materials discovery is being pushed by incredible advances in theory and modeling to help find new materials faster and predict their behavior more accurately, in chemical synthesis, and in the characterization of new materials as well as what happens when they work together. That means we’re talking about bringing together scientists and engineers who think about problems from very different angles. To successfully invent, understand and scale the next generation rechargeable battery, collaboration and learning from very disparate ways of thinking must come together. We need to encourage people to understand each other’s scientific languages so they can better work together. The 2019 Nobel Prize for Chemistry[13] recognizes the incredible advances that can be made when that approach is implemented.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[14]. ]

References

- ^ Nobel Prize in Chemistry (www.nobelprize.org)

- ^ developing its three main components (www.nobelprize.org)

- ^ I am a solid state electrochemist (sites.chem.colostate.edu)

- ^ M. Stanley Whittingham (www.nobelprize.org)

- ^ © Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (www.nobelprize.org)

- ^ CC BY-NC (creativecommons.org)

- ^ © Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (www.nobelprize.org)

- ^ CC BY-NC (creativecommons.org)

- ^ © Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (www.nobelprize.org)

- ^ CC BY-NC (creativecommons.org)

- ^ John B. Goodenough (www.nobelprize.org)

- ^ Akira Yoshino’s (www.nobelprize.org)

- ^ 2019 Nobel Prize for Chemistry (www.nobelprize.org)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Amy Prieto, Professor of Chemistry, Colorado State University