Repealing the Clean Water Rule will swamp the Trump administration in wetland litigation

- Written by Patrick Parenteau, Professor of Law, Vermont Law School

The question of which streams, lakes, wetlands and other water bodies across the U.S. should receive federal protection under the Clean Water Act has been a major controversy in environmental law over the past 20 years. The latest twist came on Sept. 9, 2019, when U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Andrew Wheeler and Army Assistant Secretary R.D. James signed a final rule[1] repealing the Obama administration’s “Clean Water Rule[2].”

This regulation was intended to resolve uncertainty created by a fractured 2006 Supreme Court decision, Rapanos v. United States[3]. The Rapanos ruling caused widespread confusion about which waters were covered, creating uncertainty for farmers, developers and conservation groups[4].

Efforts to clarify it through informal guidance or congressional action had failed, so the Obama administration proposed a new rule. It acted under mounting pressure from various quarters, including some members of the Supreme Court.

Announcing the repeal, Wheeler and James asserted that they were “providing greater regulatory certainty[5]” and ending a federal power grab. But they face a stiff challenge from the rule’s supporters, including more than a dozen state attorneys general[6], and courts may not buy their arguments.

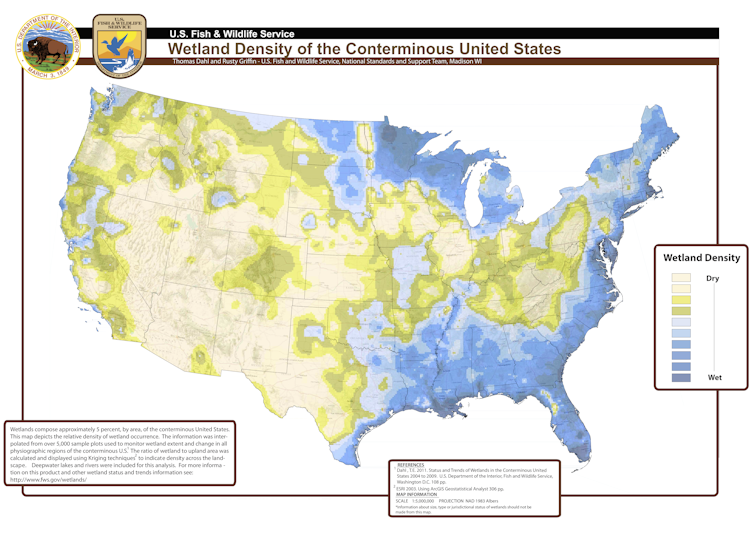

Wetlands are most common in the eastern and midwestern U.S., but also play important ecological roles in the West, even if they are only wet for part of the year.

USFWS[7]

Wetlands are most common in the eastern and midwestern U.S., but also play important ecological roles in the West, even if they are only wet for part of the year.

USFWS[7]

Rule changes require evidence

Under the Administrative Procedure Act[8], federal agencies must follow specific steps when they seek to establish or repeal a regulation. These procedures are meant to establish efficiency, consistency and accountability. To promote fairness and transparency, the law requires that the public must have meaningful opportunity to comment on proposed rules before they take effect.

The Clean Water Rule emerged from an extensive rule-making process that featured a 120-day public comment period and over 400 meetings with state, tribal and local officials and numerous stakeholders representing business, agriculture, environmental and public health organizations. It generated over one million comments, the bulk of which supported the rule[9].

This process followed a comprehensive peer-reviewed scientific assessment[10] that synthesized over 1,000 studies documenting the importance of small streams and wetlands[11] to the health of large rivers, lakes and estuaries. According to a 2015 fact sheet[12], which has been scrubbed from EPA’s website, the rule protected streams that roughly one in three Americans depend upon for their drinking water.

Importantly, EPA does not dispute any findings of the peer-reviewed scientific studies that the Obama administration cited to support its approach. Nor does the agency contend that any relevant facts or circumstances have changed since 2015. Its economic analysis has been heavily criticized by economists[13] for opting not to assign economic benefits to wetland protection.

Instead, the Trump administration relies on a legal argument[14] that the 2015 rule exceeds EPA’s authority, misreads applicable Supreme Court decisions and fails to show proper respect to states’ rights to use their land and water resources as they see fit.

EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler and other Trump administration officials argue that farmers will benefit from repealing the Clean Water Rule. Opponents say the rule had little actual impact on farmers.

AP Photo/Mark Humphrey[15]

EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler and other Trump administration officials argue that farmers will benefit from repealing the Clean Water Rule. Opponents say the rule had little actual impact on farmers.

AP Photo/Mark Humphrey[15]

Justify your action

Parties are now lining up to sue EPA, and thanks to a 2017 Supreme Court decision[16], those lawsuits can be filed in federal district courts anywhere in the U.S. In weighing challenges, the key question courts must address is whether EPA’s action is “arbitrary and capricious,” meaning that the agency has failed to consider important aspects of the problem or explain its reasoning.

In a seminal 1983 decision[17], the Supreme Court ruled that an agency must supply a “reasoned analysis” when it rescinds a rule adopted by a previous administration. The court acknowledged that agencies have some discretion to change direction in response to changing circumstances. However, it noted that “the forces of change do not always or necessarily point in the direction of deregulation.”

Further, the court said that a decision to rescind a rule would be arbitrary and capricious if it offers an explanation “that runs counter to the evidence before the agency.”

EPA asserts that the repeal “need not be based upon a change of facts or circumstances,” citing a 2009 opinion by Justice Antonin Scalia[18]. But in my view as a legal scholar, EPA reads too much into that decision, which simply held that an agency did not face “heightened scrutiny” – that is, an extra-high bar – when changing policy, but must still “show that there are good reasons for the new policy.”

As Justice Stephen Breyer observed, dissenting in the same case:

“Where does, and why would, the Administrative Procedure Act grant agencies the freedom to change major policies on the basis of nothing more than political considerations or even personal whim?”

Does Wheeler have good reasons? Let’s consider them.

Ducks Unlimited, a conservation group founded by hunters, advocates for wetland protection.Will states fill the gap?

Wheeler argues for repealing the Clean Water Rule because it fails to give enough weight to federalism principles[19] embodied in section 101(b) of the Clean Water Act. That provision expresses a policy to preserve the responsibilities and rights of states to eliminate pollution and plan for the development of land and water.

But nothing in the Clean Water Rule impedes states’ ability to do this. States are free to impose more stringent limitations than the federal government on activities that impair water quality. They just can’t allow more lenient standards that end up not only polluting their own waters but their downstream neighbors as well.

EPA admits that repealing the 2015 rule will mean less protection for streams and wetlands[20], but argues that states will fill the gap. But according to a 50-state survey[21] by the Environmental Law Institute, 36 states “have laws that could restrict the authority of state agencies or localities to regulate waters left unprotected by the federal Clean Water Act.” Only 23 states have laws regulating wetland alteration[22]. Inconsistent state regulation of water polluters led to enactment of the 1972 Clean Water Act in the first place.

A river of lawsuits

The Trump adminstration’s relentless assault on environmental regulations has not fared well in court. According to statistics compiled by New York University Law School, the administration has lost over 90% of lawsuits[23] challenging its deregulatory policy – often for failing to comply with the Administrative Procedure Act[24].

Repealing the Clean Water Rule ensures only that uncertainty about which waters are federally protected will persist for years, as multiple courts wrestle with the issues and come up with different results. This has already occurred with challenges to the Obama rule[25].

It will be years before this litigation winds upward through the courts, and eventually perhaps to the Supreme Court. The best prospect for a lasting resolution would be for Congress to take responsibility for clarifying and modernizing the nation’s premier water-quality law.

This is an updated version of an article[26] originally published on July 5, 2017.

References

- ^ signed a final rule (www.epa.gov)

- ^ Clean Water Rule (theconversation.com)

- ^ Rapanos v. United States (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ farmers, developers and conservation groups (theconversation.com)

- ^ providing greater regulatory certainty (www.epa.gov)

- ^ more than a dozen state attorneys general (www.law.nyu.edu)

- ^ USFWS (www.fws.gov)

- ^ Administrative Procedure Act (www.archives.gov)

- ^ supported the rule (www.nwf.org)

- ^ comprehensive peer-reviewed scientific assessment (cfpub.epa.gov)

- ^ small streams and wetlands (theconversation.com)

- ^ 2015 fact sheet (19january2017snapshot.epa.gov)

- ^ heavily criticized by economists (environment.yale.edu)

- ^ relies on a legal argument (www.epa.gov)

- ^ AP Photo/Mark Humphrey (www.apimages.com)

- ^ 2017 Supreme Court decision (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ seminal 1983 decision (caselaw.findlaw.com)

- ^ 2009 opinion by Justice Antonin Scalia (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ federalism principles (www.npr.org)

- ^ less protection for streams and wetlands (www.eenews.net)

- ^ 50-state survey (www.eli.org)

- ^ regulating wetland alteration (www.eli.org)

- ^ lost over 90% of lawsuits (policyintegrity.org)

- ^ failing to comply with the Administrative Procedure Act (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ challenges to the Obama rule (www.americanbar.org)

- ^ article (theconversation.com)

Authors: Patrick Parenteau, Professor of Law, Vermont Law School