What's private depends on who you are and where you live

- Written by Richard Wilk, Distinguished Professor and Provost's Professor of Anthropology; Director of the Open Anthropology Institute, Indiana University

Citizens and policymakers around the world are grappling with how to limit companies’ use of data about individuals – and how private various types of information should be. But anthropologists like me[1] know that cultures vary widely in their views of what is private and who is responsible for protecting privacy. Just like online privacy, real-world privacy can vary from person to person and situation to situation.

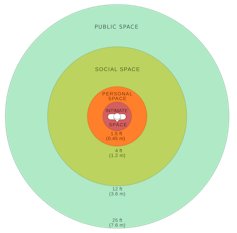

Most concepts of privacy start with the physical body. Social scientists have found that every person has an intimate zone[2] very near their body, a wider personal zone and, beyond that, a social zone and then a public zone.

One scholar’s measurements of the different types of personal space.

WebHamster/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA[3][4]

One scholar’s measurements of the different types of personal space.

WebHamster/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA[3][4]

The size of those zones and the solidity of the boundaries between them vary across cultures[5]: Mexicans, for instance, have smaller intimate zones than Anglo-Americans, so when one person from each background is speaking, the Mexican will move closer, seeking to get the Anglo into his personal zone. The Anglo will perceive that as an invasion of intimate space and back away. The Mexican may perceive the retreat as being standoffish, and may seek to reengage by moving closer again. People can easily feel threatened in a crowded public space, where strangers are in their intimate zones.

Many cultures also define privacy in terms of zones of the body and the kinds of people who are allowed to make physical contact. For example, in many cultures, men who are friends hold hands and touch each other’s face and torso. In other cultures, though, that sort of contact is limited to romantic partners.

Bodily substances like saliva, urine, fingernails and hair are usually intensely private or secret. In many cultures, people believe that a person can use them to curse or even kill a person[6]. Letting someone touch these substances means that you trust them intimately, which explains why in some parts of Africa, people spit in the palm of their hand before shaking hands. This was common in the U.S. in the past, as well.

Who’s responsible?

In 1979 and 1980 I lived in a Kekchi[7] Maya village in southern Belize, where I learned a very different definition of privacy. Older women went topless, but nobody stared at their breasts. Large families lived together in a single room – which meant they got dressed and had sex alongside family members. Modesty was preserved because nobody looked.

Their houses were made of hand-hewn boards and sticks full of gaps and openings, so anyone could look inside if they got close, but they didn’t. Proper manners were to stand about 20 feet from the door and call out to ask if anyone was home. You could approach only if you were invited to. As an outsider, I was exempt from this protection, so I woke up every morning with a gaggle of schoolchildren peering through my walls hoping to see how the white man lived.

I noticed something similar when living in Amsterdam in 1985. I was shocked that most buildings had no blinds or coverings on their ground-floor windows[8]: Passersby could look right into someone’s living room or dining room.

People told me they didn’t feel like they were living in a fishbowl, because they expected nobody would look. Certainly no one would admit to peeping. You did not have to cover up and hide any normal behavior because you could assume nobody was watching. Even if someone was sneaking looks, they would never talk about it openly.

These examples show that even without walls, it is possible to feel that nobody is watching you, that your actions are confidential and even if someone sees you, they cannot mention it to you or report it to others – so long as a tight-knit community upholds standards of public behavior and imposes social consequences for any violations.

Shifting standards

North American and European rules about privacy and physical contact have changed dramatically in recent decades. In the 18th and 19th centuries, families slept together[9] in one room, often with many people sharing a bed[10]. Travelers in Colonial America often shared beds with strangers[11] in inns.

It wasn’t until well after the start of the 20th century that the idea took hold in the U.S. that each child must have his or her own room[12], and that boys and girls should be segregated. Many people couldn’t afford homes with enough space for those arrangements until the 1950s and 1960s, and many people still can’t afford it[13]. Other parents prefer to have their children sleep together[14].

Ideals of privacy tend to change slowly. As American homes have grown larger, older children usually have their own private space, or even a separate apartment. Still, the degree to which children and teens (as well as the elderly) are allowed to have private lives[15] is in dispute, and arguments are common[16] about parental authority and power in the family.

Protecting the public

At one time, Americans could depend on community rules and local laws to protect their privacy. Yet for the past 20 years, the U.S. government, led by administrations of both political parties, has worked to make each individual responsible[17] for their own privacy, and safety[18] in general.

For instance, there are few rules governing how corporations can exploit users’ information[19], so long as the companies tell the people in vague legal terms what they want to do – and so long as the users have a choice about it. But the choice is usually “accept” or “don’t use the software or website or service.”

This is the same regulatory spirit that allows ads to urge patients to ask doctors[20] if they need to start taking specific medications. Nobody actually has the time to read every single privacy notice[21], block telemarketers, become an expert in nutrition, check medications for dangerous interactions and make sure the people providing your food aren’t enslaved[22].

Corporations have seen opportunities to make money between the limits of private responsibility and where the government is willing to act. These companies have invaded Americans’ intimate zones and are striving to become bedmates. Unless people individually, and collectively through the government, enforce practical limits, these data-driven companies will continue that effort, whether we like it or not.

References

- ^ like me (indiana.academia.edu)

- ^ every person has an intimate zone (cyborganthropology.com)

- ^ WebHamster/Wikimedia Commons (commons.wikimedia.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ vary across cultures (www.communicationstudies.com)

- ^ curse or even kill a person (occult-world.com)

- ^ Kekchi (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ no blinds or coverings on their ground-floor windows (doi.org)

- ^ families slept together (www.fatherly.com)

- ^ many people sharing a bed (www.atlasobscura.com)

- ^ shared beds with strangers (www.atlasobscura.com)

- ^ that each child must have his or her own room (doi.org)

- ^ still can’t afford it (www.nar.realtor)

- ^ prefer to have their children sleep together (www.chicagotribune.com)

- ^ allowed to have private lives (www.empoweringparents.com)

- ^ arguments are common (yp.scmp.com)

- ^ make each individual responsible (neoliberalismeducation.pbworks.com)

- ^ their own privacy, and safety (doi.org)

- ^ corporations can exploit users’ information (theconversation.com)

- ^ urge patients to ask doctors (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ read every single privacy notice (lorrie.cranor.org)

- ^ the people providing your food aren’t enslaved (www.npr.org)

Authors: Richard Wilk, Distinguished Professor and Provost's Professor of Anthropology; Director of the Open Anthropology Institute, Indiana University

Read more http://theconversation.com/whats-private-depends-on-who-you-are-and-where-you-live-120557