America’s next big clean energy resource could come from coal mine pollution – if we can agree on who owns it

- Written by Hélène Nguemgaing, Assistant Clinical Professor of Critical Resources & Sustainability Analytics, University of Maryland

Across Appalachia, rust-colored water seeps from abandoned coal mines[1], staining rocks orange and coating stream beds with metals. These acidic discharges, known as acid mine drainage[2], are among the region’s most persistent environmental problems. They disrupt aquatic life, corrode pipes and can contaminate drinking water for decades.

However, hidden in that orange drainage are valuable metals known as rare earth elements that are vital for many technologies[3] the U.S. relies on, including smartphones, wind turbines and military jets. In fact, studies have found that the concentrations of rare earths in acid mine waste can be comparable to the amount in ores mined to extract rare earths[4].

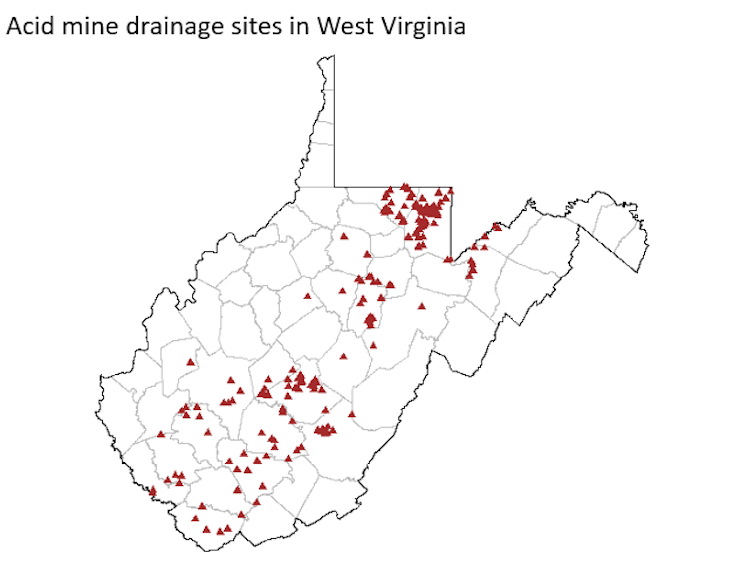

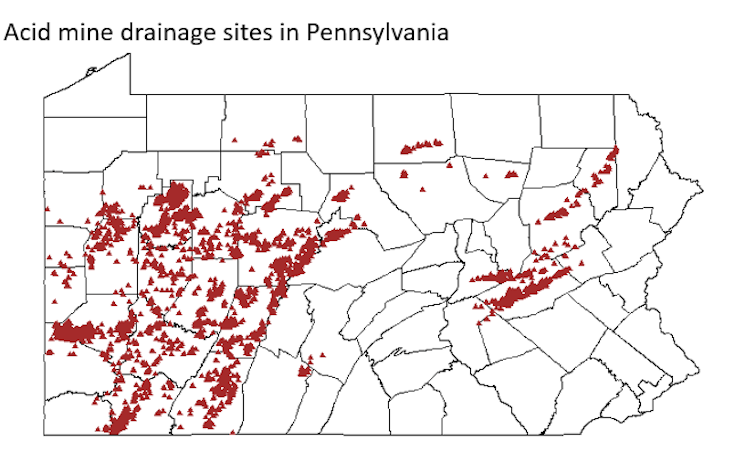

Scientists estimate that more than 13,700 miles[5] (22,000 kilometers) of U.S. streams, predominantly in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, are contaminated with acid mine discharge.

A closer look at acid mine drainage from abandoned mines in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission.We and our colleagues at West Virginia University[6] have been working on ways to turn the acid waste in those bright orange creeks into a reliable domestic source for rare earths while also cleaning the water.

Experiments show extraction can work. If states can also sort out who owns that mine waste, the environmental cost of mining might help power a clean energy future.

Rare earths face a supply chain risk

Rare earth elements[7] are a group of 17 metals, also classified as critical minerals[8], that are considered vital to the nation’s economy or security.

Despite their name, rare earth elements are not all that rare[9]. They occur in many places around the planet, but in small quantities mixed with other minerals, which makes them costly and complex to separate and refine[10].

China controls about 70% of global rare earth production and nearly all refining capacity. This near monopoly gives the Chinese government[13] the power to influence prices, export policies and access to rare earth elements. China has used that power in trade disputes as recently as 2025[14].

The United States, which currently imports about 80% of the rare earth elements it uses, sees China’s control over these critical minerals as a risk and has made locating domestic sources[15] a national priority[16].

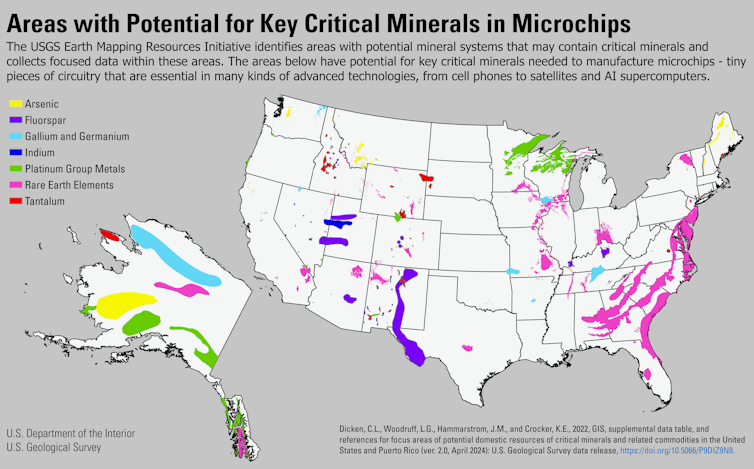

Although the U.S. Geological Survey has been mapping potential locations[18] for extracting rare earth elements, getting from exploration to production takes years[19]. That’s why unconventional sources[20], like extracting rare earth elements from acid mine waste, are drawing interest.

Turning a mine waste problem into a solution

Acid mine drainage forms when sulfide minerals, such as pyrite, are exposed to air during mining. This creates sulfuric acid, which then dissolves heavy metals such as copper, lead and mercury from surrounding rock. The metals end up in groundwater and creeks, where iron in the mix gives the water an orange color.

Expensive treatment systems can neutralize the acid, with the dissolved metals settling into an orange sludge in treatment ponds.

For decades, that sludge was treated as hazardous waste and hauled to landfills. But scientists at West Virginia University[21] and the National Energy Technology Laboratory[22] have found that it contains concentrations of rare earth elements comparable to those found in mined ores. These elements are also easier to extract from acid mine waste because the acidic water has already released them[23] from the surrounding rock.

Experiments have shown how the metals can be extracted[24]: Researchers collected sludge, separated out rare earth elements using water-safe chemistry, and then returned the cleaner water to nearby streams.

It is like mining without digging, turning something harmful into a useful resource. If scaled up, this process could lower cleanup costs[25], create local jobs and strengthen America’s supply of materials needed for renewable energy and high-tech manufacturing.

But there’s a problem: Who owns the recovered minerals?

The ownership question

Traditional mining law covers minerals underground, not those extracted from water naturally running off abandoned mine sites.

Nonprofit watershed groups that treat mine waste to clean up the water often receive public funding meant solely for environmental cleanup. If these groups start selling recovered rare earth elements, they could generate revenue for more stream cleanup projects, but they might also risk violating grant terms or nonprofit rules.

To better understand the policy challenges, we surveyed mine water treatment operators[26] across Pennsylvania and West Virginia. The majority of treatment systems were under landowner agreements in which the operators had no permanent property rights. Most operators said “ownership uncertainty” was one of the biggest barriers to investment in the recovery of rare earth elements, projects that can cost millions of dollars[27].

Not surprisingly, water treatment operators who owned the land where treatment was taking place were much more likely to be interested in rare earth element extraction.

West Virginia took steps in 2022 to boost rare earth recovery, innovation and cleanup of acid mine drainage. A new law[28] gives ownership of recovered rare earth elements to whoever extracts them. So far, the law has not been applied to large-scale projects.

Across the border, Pennsylvania’s Environmental Good Samaritan Act[29] protects volunteers who treat mine water from liability but says nothing about ownership.

Map of acid mine drainage sites in Pennsylvania.

Created by Helene Nguemgaing, based on data from Pennsylvania Spatial Data Access

Map of acid mine drainage sites in Pennsylvania.

Created by Helene Nguemgaing, based on data from Pennsylvania Spatial Data Access

This difference matters. Clear rules like West Virginia’s provide greater certainty, while the lack of guidance in Pennsylvania can leave companies and nonprofits hesitant about undertaking expensive recovery projects. Among the treatment operators we surveyed, interest in rare earth element extraction was twice as high in West Virginia than in Pennsylvania.

The economics of waste to value

Recovering rare earth elements from mine water won’t replace conventional mining. The quantities available at drainage sites are far smaller than those produced by large mines, even though the concentration can be just as high, and the technology to extract them from mine waste is still developing.

Still, the use of mine waste offers a promising way to supplement the supply of rare earth elements with a domestic source and help offset environmental costs while cleaning up polluted streams.

Early studies[30] suggest that recovering rare earth elements using technologies being developed today could be profitable, particularly when the projects also recover additional critical materials, such as cobalt and manganese, which are used in industrial processes and batteries. Extraction methods[31] are improving, too[32], making the process safer, cleaner and cheaper.

Government incentives[33], research funding and public-private partnerships could speed this progress, much as subsidies support fossil fuel extraction[34] and have helped solar and wind power scale up in providing electricity.

Treating acid mine drainage and extracting its valuable rare earth elements offers a way to transform pollution into prosperity. Creating policies that clarify ownership, investing in research and supporting responsible recovery could ensure that Appalachian communities benefit from this new chapter, one in which cleanup and clean energy advance together.

References

- ^ abandoned coal mines (www.epa.gov)

- ^ acid mine drainage (www.usgs.gov)

- ^ vital for many technologies (www.usgs.gov)

- ^ comparable to the amount in ores mined to extract rare earths (www.energy.senate.gov)

- ^ more than 13,700 miles (uwaterloo.ca)

- ^ at West Virginia University (www.energy.senate.gov)

- ^ Rare earth elements (www.energy.gov)

- ^ critical minerals (www.usgs.gov)

- ^ rare earth elements are not all that rare (doi.org)

- ^ complex to separate and refine (bipartisanpolicy.org)

- ^ Tmy350/Wikimedia Commons (commons.wikimedia.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Chinese government (doi.org)

- ^ as recently as 2025 (www.csis.org)

- ^ locating domestic sources (www.energy.gov)

- ^ national priority (www.war.gov)

- ^ USGS (www.usgs.gov)

- ^ mapping potential locations (www.usgs.gov)

- ^ takes years (cdn.ihsmarkit.com)

- ^ unconventional sources (theconversation.com)

- ^ West Virginia University (www.energy.senate.gov)

- ^ National Energy Technology Laboratory (netl.doe.gov)

- ^ already released them (www.energy.senate.gov)

- ^ how the metals can be extracted (netl.doe.gov)

- ^ lower cleanup costs (doi.org)

- ^ surveyed mine water treatment operators (papers.ssrn.com)

- ^ cost millions of dollars (wvutoday.wvu.edu)

- ^ new law (www.wvlegislature.gov)

- ^ Environmental Good Samaritan Act (www.pa.gov)

- ^ Early studies (doi.org)

- ^ Extraction methods (netl.doe.gov)

- ^ improving, too (netl.doe.gov)

- ^ Government incentives (www.energy.gov)

- ^ subsidies support fossil fuel extraction (theconversation.com)

Authors: Hélène Nguemgaing, Assistant Clinical Professor of Critical Resources & Sustainability Analytics, University of Maryland