Congress takes up health care again − and impatient voters shouldn’t hold their breath for a cure

- Written by SoRelle Wyckoff Gaynor, Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Politics, University of Virginia

As the bell struck midnight on Jan. 1, 2026, time ran out on Obamacare subsidies for over 24 million Americans[1]. These subsidies, propped up through various legislative packages over the years, lowered the health insurance costs for Americans on the Obamacare exchange.

Following the expiration of these subsidies, health insurance premiums are skyrocketing[2] for around 90% of Americans who use health insurance from the exchange. For many Americans, the new year means a choice[3] between paying exorbitant costs or taking the risk of no health insurance at all.

But unlike other policy challenges that Congress may face in 2026, the expiration of health insurance subsidies was not unexpected.

The extension of health care subsidies was the pivotal disagreement that ultimately led to the longest government shutdown[4] in U.S. history in the fall of 2025. Democratic members, in support of extending the subsidies, faced off against the majority party in Congress: Republicans who wanted a short-term legislative fix that did not fund subsidies.

Republicans ultimately won the shutdown battle[5]. And while Democrats attempted a last-gasp vote in December[6] to reform and extend health care subsidies, the health care debate was yet again punted into the next year.

Congress has reconvened, and Democratic members – joined by four Republican members – used the best possible procedural tool at the minority party’s disposal, the discharge petition, to force congressional leaders to allow votes on an extension of Obamacare subsidies[7] during its first week back in session. But overcoming congressional leadership is an immense challenge: Even if the House is successful, Senate Republican leadership has made clear[8] that there is no future for the legislation in that chamber.

The challenge of passing meaningful solutions to rising health care costs is not unique to this year or to this Congress. It has been a decades-long argument among lawmakers that shows no sign of being resolved.

Why is it so hard for Congress to lower the cost of health care for the people who sent them to Washington?

Like many policy problems, partisanship is partly to blame. But the sprawling complexities of the American health care system pose a particular challenge to members of Congress. As my own research finds[9], the outsized power and resources of congressional leaders means that for Congress’ most intricate issues, rank-and-file members do not have the time, resources or, frankly, the interest to dedicate to meaningful problem-solving.

The failure of two health care proposals in December 2025, one from Democrats and one from Republicans, meant certain Obamacare enrollees face huge premium increases.Government ‘dips its toe’

Americans face some of the highest health care costs in the world[10]. Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have long campaigned on addressing exorbitant costs and equitable access.

Progressive politicians proposed the idea of national health insurance as early as the 1900s, but efforts were limited to women and children[11], and any policy successes were moderate and temporary.

Following the Great Depression and the advent of Social Security in the 1940s, Congress had warmed to the idea of the federal government providing social services. But attempts at widespread health care coverage[12] failed to gain traction.

During the 1950s, as Americans began to expect more services from their tax dollars, formal coalitions formed in support of, and in opposition to, government-supported health care. Workers and unions, bolstered by Congress and the Supreme Court[13], used the power of collective bargaining to push for employee benefits such as health insurance. Doctors and medical providers, enjoying their current – and profitable – position, coordinated campaigns against[14] national health insurance proposals.

The tension held until 1956, when the government dipped its toe into federally funded health care, enacting the first “Medicare” government-funded program for dependents of the armed forces[15].

In the private sector, employee demands and employer tax incentives[16] led to a convoluted web of employer-based insurance programs. But for many Americans, particularly the retired and elderly and those with low-paying jobs, there remained few, if any, insurance options available.

Enter: Medicare and Medicaid

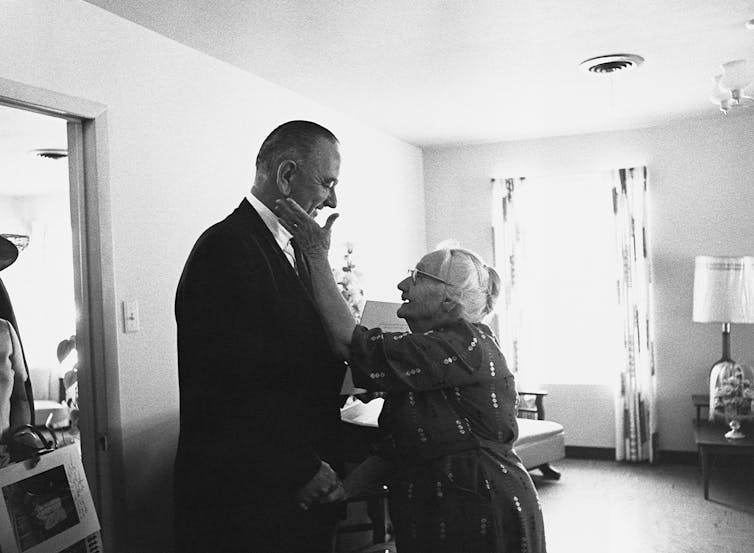

In the 1960s, under Democratic President Lyndon Johnson’s vision for a “Great Society[17],” and with a bipartisan vote in Congress, the federal government took the greatest step forward in providing federal health assistance for Americans: Medicare and Medicaid. The programs helped with the cost of health care via federal health insurance for those who were elderly and low-income, and they ushered in a new era of federal health policy.

This was a watershed moment for policymakers. With health care coverage now under the umbrella of the federal government, domestic policymaking responsibility expanded[18] to match. For lawmakers, this meant not only new debates but also new federal agencies, new congressional committees, new lobbying firms and new interest group coalitions.

In the decades that followed, Congress’ responsibility for health care policy continued to expand: Coverage amounts and eligibility requirements were tweaked, programs were expanded[20] to include prescription drugs and vaccines, health savings accounts[21] were introduced, and more.

Yet still, the web of private and federal health insurance programs left millions of Americans uninsured. It wasn’t until 2010, under President Barack Obama, that the Democratic-controlled House and Senate passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act[22], known as “Obamacare,” to close that gap. But as evident from the 2025 government shutdown, this solution was far from perfect – and quite expensive.

Why, despite centuries of attention, does health care coverage remain one of – if not the most – perplexing and challenging domestic issues that Congress faces?

Consensus becomes more difficult

Part of this is a uniquely American problem: Like many services, the American health care system is based on economic incentives, and the foundational ideal of American liberalism means the government is inclined to let capitalism thrive.

As a former congressional staffer[23] and now a scholar of Congress[24], I know that nowhere is the tension of societal support and personal freedom more apparent than the debate over health care access.

But the issue is also immensely complex, and today’s Congress does not have the resources to meet the challenge, particularly in the face of a sprawling executive branch.

Over time, as policies were adopted by the federal government, the scope of potential solutions expanded[25]. To put it another way, as more cooks enter the policymaking kitchen, consensus became more difficult. The history of American health care is populated by private industries, powerful interest groups, federal officials and concerned citizens.

And the web of federal funding and private insurance companies across 50 states has resulted in a policy landscape that is easier to tweak, rather than whole-scale reform.

This is further stymied by the limited resources and expertise of the modern Congress. My research[26] has shown that rank-and-file members are increasingly reliant on party leaders to take the lead on policymaking and problem-solving. Negotiating across coalitions and parties is unpleasant, and communicating policy changes on such a complex issue is difficult.

The result? Tepid policy tweaks made for partisan messaging.

And as ideological divisions on government support and personal autonomy become crystallized by the two parties in Congress, partisan policy solutions diverge even further. Collaboration becomes harder every year.

The continuing resolution passed late in 2025 funded the government only until Jan. 30, 2026[27], which means Congress is facing a Groundhog Day rather than a clean slate for the new year. With millions of Americans facing exploding health care costs, the question becomes who will Congress follow: party leadership or concerned constituents?

References

- ^ 24 million Americans (www.kff.org)

- ^ health insurance premiums are skyrocketing (www.kff.org)

- ^ means a choice (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ longest government shutdown (www.npr.org)

- ^ ultimately won the shutdown battle (www.cbsnews.com)

- ^ last-gasp vote in December (www.nbcnews.com)

- ^ force congressional leaders to allow votes on an extension of Obamacare subsidies (www.politico.com)

- ^ Senate Republican leadership has made clear (punchbowl.news)

- ^ my own research finds (sorellewg.com)

- ^ highest health care costs in the world (www.healthsystemtracker.org)

- ^ efforts were limited to women and children (history.house.gov)

- ^ attempts at widespread health care coverage (www.ssa.gov)

- ^ bolstered by Congress and the Supreme Court (history.house.gov)

- ^ coordinated campaigns against (doi.org)

- ^ Medicare” government-funded program for dependents of the armed forces (www.congress.gov)

- ^ employee demands and employer tax incentives (account.ache.org)

- ^ under Democratic President Lyndon Johnson’s vision for a “Great Society (www.archives.gov)

- ^ domestic policymaking responsibility expanded (press.uchicago.edu)

- ^ Corbis via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ programs were expanded (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ health savings accounts (motivhealth.com)

- ^ Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (www.kff.org)

- ^ a former congressional staffer (sorellewg.com)

- ^ now a scholar of Congress (scholar.google.com)

- ^ the scope of potential solutions expanded (press.uchicago.edu)

- ^ My research (sorellewg.com)

- ^ funded the government only until Jan. 30, 2026 (www.govexec.com)

Authors: SoRelle Wyckoff Gaynor, Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Politics, University of Virginia