The unraveling of workplace protections for delivery drivers: A tale of 2 workplace models

- Written by Daniel Schneider, Professor of Social Policy, Harvard Kennedy School

American households have become dependent on Amazon.

The numbers say it all[1]: In 2024, 83% of U.S. households received deliveries from Amazon, representing over 1 million packages delivered each day and 9 billion individual items delivered same-day or next-day every year. In remarkably short order, the company has transformed from an online bookseller into a juggernaut that has reshaped retailing. But its impact isn’t limited to how we shop.

Behind that endless stream of packages are more than a million people[2] working in Amazon fulfillment centers and delivery vehicles. Through its growing dominance in retail, Amazon has eclipsed its two major competitors[3] in the delivery business, UPS and FedEx, in terms of package volume.

What is life like for those workers? Between Amazon’s rosy public relations[4] on the one hand and reporters’[5] and advocates’[6] troubling exposés on the other, it can be hard to tell. Part of the reason is that researchers[7] like us[8] don’t have much reliable data: Workers’ experiences at companies such as Amazon, UPS and FedEx can be a black box. Amazon’s arm’s-length relationship with the drivers it depends on for deliveries makes finding answers even harder.

But that didn’t stop us. Using unique data from the Shift Project[9], our new study, co-authored with Julie Su[10] and Kevin Bruey[11], offers the first direct, large-scale comparison[12] of working conditions for drivers and fulfillment employees at Amazon, UPS and FedEx based on survey responses by more than 9,000 workers.

What we found was deeply troubling – not only for Amazon drivers but also for the future of work in the delivery industry as a whole.

For nearly a century, driving delivery trucks has been a pathway to the middle class, as epitomized by unionized jobs[13] at UPS[14]. UPS drivers, who have been members of the Teamsters union for decades, are employees with legal protections and a collective-bargaining contract.

In contrast, Amazon has embraced a very different model. Most important is that Amazon does not directly employ nearly any of its delivery drivers.

Instead, its transportation division, Amazon Logistics, relies on two methods to deliver most of its shipments: Amazon Flex, a platform-like system that treats drivers like independent contractors[15], and Amazon DSP, a franchise-like system that uses subcontractors. DSP subcontractors are almost all nonunion, and the company has cut ties with DSP contractors whose drivers have attempted to unionize[16]. These practices place downward pressure on the wages and working conditions of drivers throughout the industry.

The impact on workers is stark.

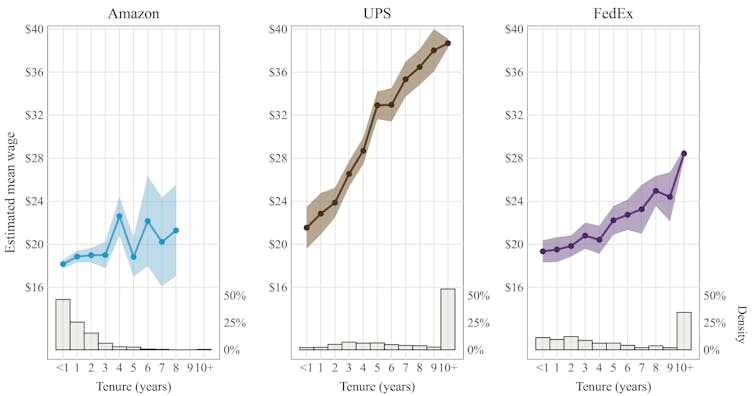

Delivery workers at Amazon receive significantly lower wages[17] than at UPS and FedEx, we found. Wage gaps are especially large between the delivery workers at Amazon, who earn US$19 an hour on average, and the unionized drivers at UPS, who make $35.

We also found that unionized UPS drivers have a clear pathway to upward mobility, while Amazon drivers don’t. At UPS, wages increase sharply the longer a worker has been on the job. Pay starts at $21 an hour, reaching nearly $40 an hour for drivers who’ve been with the company for at least 10 years – which is more than half of them.

At Amazon, wages start at $17 an hour and don’t increase with tenure. Nearly half of workers have less than a year on the job.

References

- ^ The numbers say it all (redstagfulfillment.com)

- ^ more than a million people (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ eclipsed its two major competitors (www.wsj.com)

- ^ public relations (hiring.amazon.com)

- ^ reporters’ (www.vox.com)

- ^ advocates’ (www.nelp.org)

- ^ researchers (inequality.hks.harvard.edu)

- ^ like us (www.hks.harvard.edu)

- ^ the Shift Project (shift.hks.harvard.edu)

- ^ Julie Su (tcf.org)

- ^ Kevin Bruey (shift.hks.harvard.edu)

- ^ the first direct, large-scale comparison (shift.hks.harvard.edu)

- ^ unionized jobs (about.ups.com)

- ^ UPS (www.wiley.com)

- ^ independent contractors (theconversation.com)

- ^ attempted to unionize (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ receive significantly lower wages (shift.hks.harvard.edu)

- ^ Source: Amazon Drives Low Wages: The Unraveling of Workplace Protections for Delivery Drivers (shift.hks.harvard.edu)

- ^ an extreme case of worker monitoring and performance assessment (shift.hks.harvard.edu)

- ^ revenues (www.reuters.com)

- ^ stock value (finance.yahoo.com)

- ^ market capitalization (www.macrotrends.net)

- ^ Recent reporting (www.wsj.com)

Authors: Daniel Schneider, Professor of Social Policy, Harvard Kennedy School