A county in Idaho offered Spanish-language ballots for the first time and here's what happened

- Written by Gabe Osterhout, Research Associate, Idaho Policy Institute, Boise State University

On the morning of Election Day, the top trending search on Google was “donde votar[1],” which means “where to vote” in Spanish.

Voter access to the polls was a major issue[2] during the 2018 midterm elections in the U.S. Charges of voter suppression were made in in Georgia and North Dakota. Critics of new voting rules claimed they disenfranchised African-Americans and Native Americans.

While those problems were extensively covered by the press, less attention was paid to another problem that can affect voter turnout: the availability of foreign-language ballots.

Lack of access to non-English ballots can be an obstacle to voting for immigrants[3]. Simply put, if voters can’t understand the ballot, they may not vote.

That’s why the Voting Rights Act[4] has protections for language minorities[5], defined as “persons who are American Indian, Asian American, Alaskan Natives, or of Spanish heritage.” The act requires local election officials to provide foreign-language election materials in regions that have a certain number of voters with limited English proficiency. Election materials[6] can include registration or voting notices, instructions and ballots.

After the 2016 election, the Census Bureau released a list of 263 jurisdictions in 29 states required to offer such foreign-language election materials[7]. Those areas included close to 70 million voters with limited English who could vote in the 2018 election. For the first time, Idaho had a jurisdiction required to offer Spanish-language ballots.

I’m a researcher[8] at Boise State University’s Idaho Policy Institute where I study the impact of electoral policy on voter turnout and outcomes. I examined how this new requirement affected voter behavior on Election Day in Idaho.

While my findings seem to be an outlier in the larger context of election language assistance studies, the experience of one county may help broaden our understanding of the impact of foreign-language ballots as the Hispanic population continues to grow[9] in Idaho and elsewhere.

The curious case of Idaho

Idaho has 80,000 Hispanic voters, 7 percent of Idaho’s eligible voter population[10]. Lincoln County is a small, rural area in southern Idaho. It has slightly more than 5,000 residents, including 1,600 Hispanics[11], representing 30 percent of the county’s population. Among those that speak Spanish at home, 60 percent do not speak English very well[12].

I studied Lincoln County’s turnout[13] before and after the 2018 election to see if election language assistance affected voter behavior in the Latino community.

Compared to previous midterm elections, the county’s 68 percent turnout was higher than in 2014, 2010 and 2006[14]. However, this year’s elections also saw higher voter turnout[15] across Idaho and the United States, which makes it difficult to isolate the impact of Spanish-language ballots.

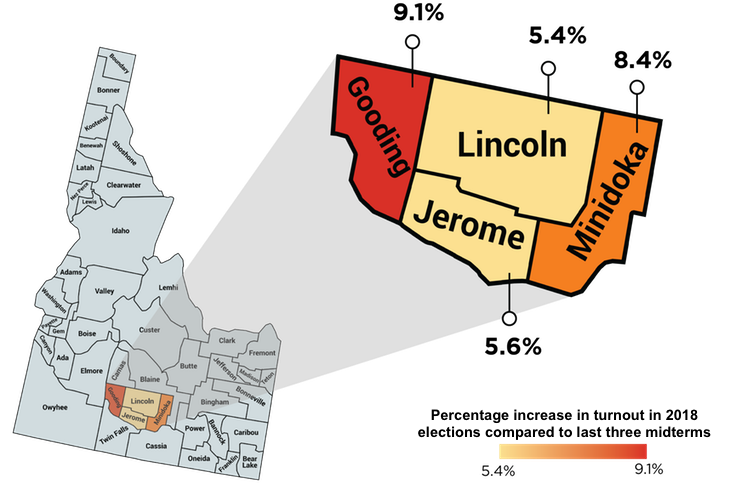

To dig deeper, I compared voter turnout in Lincoln to three neighboring and demographically similar counties: Minidoka, Jerome and Gooding. The four counties all have Hispanic populations ranging from 29 percent to 34 percent of the population[16]. But unlike Lincoln, its neighboring counties were not required to offer Spanish-language ballots.

Map showing the percentage increase in turnout in 2018 from the previous three midterm years in four counties in Idaho.

CC BY-SA[17]

Map showing the percentage increase in turnout in 2018 from the previous three midterm years in four counties in Idaho.

CC BY-SA[17]

I found that Lincoln County’s voter turnout didn’t increase in 2018 from the previous three midterms any more than its neighbors.

Turnout in Lincoln rose 5.4 percent[18] compared to the previous three midterm elections, while Jerome[19] rose 5.6 percent, Minidoka[20] rose 8.4 percent, and Gooding[21] rose 9.1 percent. These three counties had higher rates of increased voter turnout compared to recent midterms than Lincoln County did.

Does this mean that Spanish-language ballots don’t affect Hispanic election participation? From this case, it’s hard to tell.

Here’s what we know based on previous research.

The bigger picture

Counties that offered language assistance in previous elections have experienced increased minority participation. Since the Voting Rights Act was amended to include minority language assistance in 1975, Hispanic voter registration doubled over the following 30 years[22]. Language assistance has a significant effect on voting turnout for minority groups, especially for first-generation citizens[23].

Other studies show that, despite helping increase voter turnout, election language assistance does not help increase voter registration[24] for people who don’t speak English fluently. This is an important consideration since voter turnout compares the number of ballots cast to the number of registered voters, not the total population.

Overall, studies show that foreign-language assistance, and especially Spanish-language ballots, make it easier for immigrant populations[25] to engage in the election process and have increased voter turnout among Hispanic citizens.

The turnout in Lincoln County, Idaho this year seems to be an outlier. This may be due to a few reasons. For one, the small sampling size of a sparsely populated county means that even minor changes in voting behavior can create erratic statistical swings. Further, with 2018 being Lincoln County’s first major election to offer Spanish ballots, we can only look at one data point. Its turnout numbers will become more reliable and significant as future elections take place and offer more data points. As the first bilingual election, it is also possible that some members of the community were not aware of the opportunity to vote in another language.

Lincoln County also has a significantly lower percentage of registered[26] Democratic voters compared to other regions in the country offering foreign-language ballots. This is important because turnout in 2018 was higher in liberal-leaning areas[27].

There are likely other electoral factors at play that need more consideration, but these findings will perhaps prove helpful, as other Idaho counties will likely be required to offer[28] Spanish-language ballots after the next census as the state’s Hispanic population continues to grow.

References

- ^ top trending search on Google was “donde votar (abcnews.go.com)

- ^ major issue (www.bbc.com)

- ^ obstacle to voting for immigrants (www.jstor.org)

- ^ Voting Rights Act (www.census.gov)

- ^ language minorities (www.justice.gov)

- ^ Election materials (www.justice.gov)

- ^ foreign-language election materials (www.pewresearch.org)

- ^ researcher (sps.boisestate.edu)

- ^ Hispanic population continues to grow (www.idahostatejournal.com)

- ^ eligible voter population (www.pewhispanic.org)

- ^ 5,000 residents, including 1,600 Hispanics (www.statsamerica.org)

- ^ 60 percent do not speak English very well (factfinder.census.gov)

- ^ Lincoln County’s turnout (lincolncountyid.us)

- ^ 2014, 2010 and 2006 (sos.idaho.gov)

- ^ higher voter turnout (www.npr.org)

- ^ 29 percent to 34 percent of the population (icha.idaho.gov)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ 5.4 percent (lincolncountyid.us)

- ^ Jerome (www.jeromecountyid.us)

- ^ Minidoka (www.minidoka.id.us)

- ^ Gooding (www.goodingcounty.org)

- ^ Hispanic voter registration doubled over the following 30 years (heinonline.org)

- ^ especially for first-generation citizens (search.ebscohost.com)

- ^ does not help increase voter registration (doi.org)

- ^ make it easier for immigrant populations (www.jstor.org)

- ^ lower percentage of registered (sos.idaho.gov)

- ^ liberal-leaning areas (www.npr.org)

- ^ will likely be required to offer (www.idahopress.com)

Authors: Gabe Osterhout, Research Associate, Idaho Policy Institute, Boise State University