What was the first thing scientists discovered? A historian makes the case for Babylonian astronomy

- Written by James Byrne, Assistant Teaching Professor in the Herbst Program for Engineering, Ethics & Society, University of Colorado Boulder

For the Babylonians, those ideas were linked. They saw changes in the motions of the planets or rare events such as eclipses as signs – omens – about what was going to happen on Earth. For example, they might think the shadow of the Earth moving over the Moon in a certain way during a lunar eclipse meant that a flood would also happen.

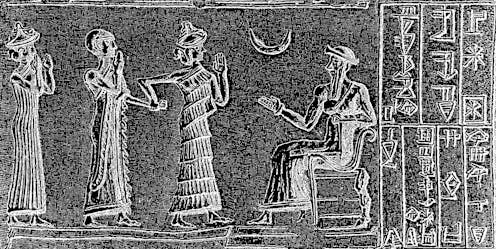

The scribes kept a book called Enūma Anu Enlil[9] listing omens and their meanings. So if the seemingly changing motions of the heavens could be predicted, maybe earthly events could be, too. This led the scribes to study astronomy.

How Babylonian astronomy worked

The foundation of Babylonian astronomy was kept in a book called MUL.APIN[10], meaning “The Plough Star,” the name of a constellation. It recorded the positions of the stars, when in the year they would first be visible, the paths of the Sun and Moon, the periods when the planets would be visible in the night sky, and other fundamental astronomical knowledge.

Later, Babylonian scribes began to keep their Astronomical Diaries[11], which contained detailed records of the positions of the Moon and planets along with events on Earth such as the weather and the price of grain. In other words, they recorded their observations of both astronomical omens and the events they might have predicted.

This kind of careful observation and record-keeping is a major part of science. The Astronomical Diaries were kept for over 700 years, making them maybe the longest-running scientific project ever.

The records in the Astronomical Diaries helped Babylonian scribes take another scientific step: predicting astronomical events. One part of this was computing what the Babylonians called goal-years: the number of years it took for a planet to return to the same place on the same day. For example, they computed that the period for Venus was eight Babylonian years. So if Venus was somewhere on a particular day, it would be in the same place on the same day eight years later.

By around the fourth century B.C.E., the scribes developed this knowledge into a system of mathematically predicting astronomical events. They made tables called ephemerides[13] that showed when these events would happen in the future. So Babylonian scribes succeeded in their project: They made the motions of the Sun, Moon and planets predictable.

Babylonian astronomy and you

MUL.APIN, the Astronomical Diaries, the ephemerides and all of Babylonian astronomy had a major impact on later astronomers, one that continues to today. Greek astronomers used Babylonian observations to make geometric models of planetary motions, part of the long path toward modern astronomy. The ephemerides were the ancestors of astronomical tables, which still exist. For example, NASA has a table of eclipses[14] online that goes to the year 3000.

But the most familiar thing that comes from Babylonian astronomy is how we tell time. The Babylonians didn’t use a decimal system with units of 10 like we do. Instead, they used a sexagesimal system[16], with units of 60. Babylonian observations were so important that later people kept Babylonian units for astronomy, even though they used a base 10 system for other things.

So if you’ve ever wondered why an hour has 60 minutes, and a minute has 60 seconds, it’s because we’ve kept that way of measuring from Babylonian astronomy. Whenever you tell the time, you’re using some of the very oldest science.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com[17]. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

References

- ^ Curious Kids (theconversation.com)

- ^ curiouskidsus@theconversation.com (theconversation.com)

- ^ Science (spaceplace.nasa.gov)

- ^ The Babylonians (www.britannica.com)

- ^ Babylonian astronomy (astrobites.org)

- ^ sometimes they even seem to stop (www.sciencefocus.com)

- ^ eclipses (theconversation.com)

- ^ Josh Edelson/AFP via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ Enūma Anu Enlil (brunelleschi.imss.fi.it)

- ^ MUL.APIN (brunelleschi.imss.fi.it)

- ^ Astronomical Diaries (brunelleschi.imss.fi.it)

- ^ mikroman6/Moment via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ ephemerides (www.metmuseum.org)

- ^ NASA has a table of eclipses (eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov)

- ^ Catherine McQueen/Moment via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ used a sexagesimal system (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com (theconversation.com)

Authors: James Byrne, Assistant Teaching Professor in the Herbst Program for Engineering, Ethics & Society, University of Colorado Boulder