With the end of the Hollywood writers and actors strikes, the creator economy is the next frontier for organized labor

- Written by David Craig, Clinical Associate Professor of Communication, USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

Hollywood writers and actors recently proved[1] that they could go toe-to-toe with powerful media conglomerates. After going on strike in the summer of 2023, they secured[2] better pay, more transparency from streaming services and safeguards from having their work exploited or replaced by artificial intelligence[3].

But the future of entertainment extends well beyond Hollywood. Social media creators[4] – otherwise known as influencers, YouTubers, TikTokers, vloggers and live streamers – entertain and inform a vast portion of the planet.

For the past decade, we’ve mapped the contours and dimensions of the global social media entertainment industry[5]. Unlike their Hollywood counterparts, these creators struggle to be seen as entertainers worthy of basic labor protections.

Platform policies and government regulations have proved capricious or neglectful. Meanwhile, creators’ bottom-up initiatives to collectively organize have sputtered.

Living on the edge

Industry estimates regarding the size and scale of the creator economy vary. But Citibank estimates[6] there are over 120 million creators, and an April 2023 Goldman Sachs report predicted that the creator economy would double in size, from US$250 billion to $500 billion[7], by 2027.

According to Forbes, the “Top 50 Creators[8]” altogether have 2.6 billion followers and have hauled in an estimated $700 million in earnings. The list includes MrBeast[9], who performs stunts and records giveaways, and makeup artist-cum-true crime podcaster Bailey Sarian[10].

The windfalls earned by these social media stars are the exception, not the norm.

The venture capitalist firm SignalFire[11] estimates that less than 4% of creators make over $100,000 a year, although YouTube-funded research[12] points to a rising middle class of creators who are able to sustain careers with relatively modest followings.

These are the users who find themselves most vulnerable to opaque changes to platform policies and algorithms.

Platforms like to “move fast and break things[13],” to use Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s infamous expression. And since the creator economy relies on social media platforms to reach audiences, creators’ livelihoods are subject to rapid, iterative changes in platforms’ features, services and agreements.

Yes, various platforms have introduced business opportunities for creators, such as YouTube’s advertising partnership feature or Twitch’s virtual goods store. However, the platforms’ terms of use can flip on a switch[14]. For example, in September 2022, Twitch changed its fee structure. Some streamers who were retaining 70% of all subscription revenue generated from their accounts saw this proportion drop to 50%.

In 2020, TikTok, facing rising competition from YouTube Shorts and Instagram reels, launched its billion-dollar Creator Fund. The fund was supposed to allow creators to get directly paid for their content. Instead, creators complained[15] that every 1,000 views only translated to a few cents. TikTok suspended the fund[16] in November 2023.

Bias as a feature, not a bug

The livelihoods of many fashion, beauty, fitness and food creators depend on deals brokered with brands that want these influencers to promote goods or services to their followers.

Yet throughout the creator economy, people of color and those identifying as LGBTQ+ have encountered bias. Unequal and unfair compensation from brands is a recurring issue, with one 2021 report[17] revealing a pay gap of roughly 30% between white creators and creators of color.

Along with brand biases, platforms can exacerbate systemic bias. Creator scholar Sophie Bishop[18] has demonstrated how nontransparent algorithms can categorize “desirability” among influencers along lines of race, gender, class and sexual orientation.

Then there’s what creator scholar Zoë Glatt calls the “intimacy triple bind[19]”: Marginalized creators are at higher risk of trolling and harassment, they secure lower fees for advertising, and they are expected to divulge more personal details to generate more engagement and revenue.

Couple these precarious conditions with the whims and caprices of volatile online communities that can turn beloved creators into villains in the blink of a text or post[20], and even the world’s most successful creators live on a precipice of losing their livelihoods.

Rumblings of solidarity

Unlike their counterparts in the legacy media industries, creators have neither taken easily nor well to collective action as they operate from their bedrooms and fight for more eyeballs.

Yet some members of this creator class recognize that the bedroom-boardroom power imbalance is a bottom line matter that requires bottom-up initiative.

The Creators Guild of America, or CGA, which launched in August 2023[22], is but one of many successors to the original Internet Creators’ Guild, which folded in 2019[23]. Paradoxically, CGA describes itself as a “professional service organization,” not a labor union, yet claims to offer benefits “similar to those offered by unions.”

There are other movements afoot[24]: A group of TikTok creators formed a Discord group in September 2022 to discuss unionizing. There’s also the Twitch Unity Guild[25], a program launched in December 2022 for networking, development and celebration and includes a dedicated Discord space. In response to the rampant bias in influencer marketing, creator-led firms like “F–k You Pay Me [26]” are demanding greater fairness, transparency and accountability from brands and advertisers.

Twitch streamers are already seeing some of their organizing efforts pay off. In June 2023, after a year of repeated changes in streamer fees and brand deals, the company capitulated[27] in response to the backlash of their top streamers threatening to leave.

None of these initiatives has yet attained the legal status of unions such as the Writers Guild of America. Meanwhile, efforts by the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists to recruit creators have proved limited. Legal scholar Sara Shiffman[28] has written about how SAG-AFTRA provides creators with health and retirement benefits, but offers no resources to ensure fair and equitable compensation from platforms or advertisers. Nonetheless, while on strike[29], SAG-AFTRA threatened creators that partnered with studios with a lifetime ban from joining the union.

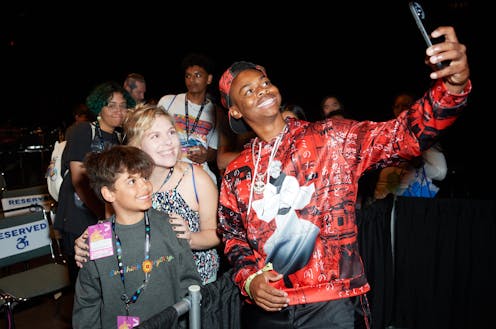

And despite these bottom-up efforts, the tech behemoths refuse to recognize creators’ fledgling organizations. When a union for YouTubers formed in Germany in 2018, YouTube refused to negotiate with it[30]. Nonetheless, you’ll see companies trot out their biggest stars when they find themselves under regulatory scrutiny. That’s what happened when TikTok sponsored creators to lobby politicians[31] who were debating banning the platform.

An invisible class of labor

Meanwhile, most governments have failed to provide support for – or even recognition of – creator rights.

Within the U.S., creators “barely exist[33]” in official records, as technology reporters Drew Harwell and Taylor Lorenz recently pointed out in The Washington Post. The U.S. Census Bureau makes no mention of social media as a profession; it is invisible as a distinctive class of labor.

To date, the Federal Trade Commission is the only U.S. agency to introduce regulation[34] tied to the work of creators, and it’s limited to disclosure guidelines for advertising and sponsored content.

Even as the European Union has operated at the forefront of tech and platform policy, creators rate scant mention in the body’s laws. Writing about the EU’s 2022 Digital Services Act, legal scholars Bram Duivendvoorde and Catalina Goanta[35] criticize the EU for leaving “influencer marketing out of the material scope of its specific rules,” a blind spot that they describe as “one of its main pitfalls.”

The success of the 2023 Hollywood strikes could be just the beginning of a larger global movement for creator rights. But in order for this new class of creators to access the full breadth of their economic and human rights – to borrow from the movie “Jaws”[36] – we’re gonna need a bigger boat.

References

- ^ writers and actors recently proved (www.cbsnews.com)

- ^ they secured (www.cbsnews.com)

- ^ having their work exploited or replaced by artificial intelligence (theconversation.com)

- ^ Social media creators (www.adobe.com)

- ^ global social media entertainment industry (nyupress.org)

- ^ Citibank estimates (ir.citi.com)

- ^ from US$250 billion to $500 billion (www.goldmansachs.com)

- ^ Top 50 Creators (www.forbes.com)

- ^ MrBeast (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Bailey Sarian (www.youtube.com)

- ^ venture capitalist firm SignalFire (www.signalfire.com)

- ^ YouTube-funded research (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ move fast and break things (www.snopes.com)

- ^ the platforms’ terms of use can flip on a switch (techcrunch.com)

- ^ creators complained (www.engadget.com)

- ^ suspended the fund (www.zdnet.com)

- ^ one 2021 report (www.prnewswire.com)

- ^ Creator scholar Sophie Bishop (doi.org)

- ^ intimacy triple bind (zoeglatt.com)

- ^ into villains in the blink of a text or post (www.insider.com)

- ^ Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ which launched in August 2023 (techcrunch.com)

- ^ which folded in 2019 (www.theverge.com)

- ^ There are other movements afoot (dot.la)

- ^ Twitch Unity Guild (blog.twitch.tv)

- ^ F–k You Pay Me (www.theverge.com)

- ^ the company capitulated (www.forbes.com)

- ^ Legal scholar Sara Shiffman (lawecommons.luc.edu)

- ^ while on strike (time.com)

- ^ YouTube refused to negotiate with it (www.theverge.com)

- ^ TikTok sponsored creators to lobby politicians (www.tubefilter.com)

- ^ Nathan Posner/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ barely exist (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ to introduce regulation (www.ftc.gov)

- ^ Bram Duivendvoorde and Catalina Goanta (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ borrow from the movie “Jaws” (www.youtube.com)

Authors: David Craig, Clinical Associate Professor of Communication, USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism