Cell death is essential to your health − an immunologist explains when cells decide to die with a bang or take their quiet leave

- Written by Zoie Magri, Ph.D. Candidate in Immunology, Tufts University

Living cells work better than dying cells, right? However, this is not always the case: your cells often sacrifice themselves to keep you healthy[1]. The unsung hero of life is death.

While death may seem passive, an unfortunate ending that just “happens,” the death of your cells is often extremely purposeful and strategic. The intricate details of how and why cells die can have significant effects on your overall health.

There are over 10 different ways cells can “decide” to die, each serving a particular purpose for the organism. My own research[2] explores how immune cells switch between different types of programmed death in scenarios like cancer or injury.

Programmed cell death can be broadly divided into two types[3] that are crucial to health: silent and inflammatory.

Quietly exiting: silent cell death

Cells can often become damaged because of age, stress or injury, and these abnormal cells can make you sick[4]. Your body runs a tight ship, and when cells step out of line, they must be quietly eliminated before they overgrow into tumors or cause unnecessary inflammation[5] where your immune system is activated and causes fever, swelling, redness and pain.

Your body swaps out cells every day[6] to ensure that your tissues are made up of healthy, functioning ones. The parts of your body that are more likely to see damage, like your skin and gut, turn over cells weekly, while other cell types can take months to years to recycle. Regardless of the timeline, the death of old and damaged cells and their replacement with new cells is a normal and important bodily process.

Silent cell death, or apoptosis[7], is described as silent because these cells die without causing an inflammatory reaction. Apoptosis is an active process involving many proteins and switches within the cell. It’s designed to strategically eliminate cells without alarming the rest of the body.

Sometimes cells can detect that their own functions are failing and turn on executioner proteins[8] that chop up their own DNA, and they quietly die by apoptosis. Alternatively, healthy cells can order overactive or damaged neighbor cells to activate their executioner proteins.

Apoptosis is important to maintaining a healthy body. In fact, you can thank apoptosis for your fingers and toes[9]. Fetuses initially have webbed fingers until the cells that form the tissue between them undergo apoptosis and die off.

Without apoptosis, cells can grow out of control. A well-studied example of this is cancer. Cancer cells are abnormally good at growing and dividing, and those that can resist apoptosis[12] form very aggressive tumors. Understanding how apoptosis works and why cancer cells can disrupt it can potentially improve cancer treatments.

Other conditions can benefit from apoptosis research as well. Your body makes a lot of immune cells that all respond to different targets, and occasionally one of these cells can accidentally target your own tissues. Apoptosis is a crucial way your body can eliminate these immune cells before they cause unnecessary damage. When apoptosis fails to eliminate these cells, sometimes because of genetic abnormalities, this can lead to autoimmune diseases[13] like lupus.

Another example of the role apoptosis plays in health is endometriosis[14], an understudied disease caused by the overgrowth of tissue in the uterus. It can be extremely painful and debilitating for patients. Researchers have recently linked this out-of-control growth in the uterus[15] to dysfunctional apoptosis.

Whether it’s for development or maintenance, your cells are quietly exiting to keep your body happy and healthy.

Going out with a bang: inflammatory cell death

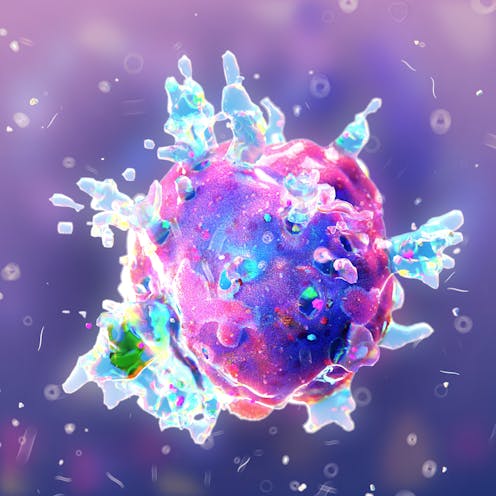

Sometimes, it is in your body’s best interest for cells to raise an alarm as they die. This can be beneficial when cells detect the presence of an infection and need to eliminate themselves as a target while also alerting the rest of the body. This inflammatory cell death[16] is typically triggered by bacteria, viruses or stress.

Rather than quietly shutting down, cells undergoing inflammatory cell death will make themselves burst, or lyse, killing themselves and exploding inflammatory messengers as they go. These messengers tell your immune cells that there is a threat and prompts them to treat and fight the pathogen.

An inflammatory death would not be healthy for maintenance. If the normal recycling of your skin or gut cells caused an inflammatory reaction, you would feel sick a lot. This is why inflammatory death is tightly controlled[17] and requires multiple signals to initiate.

Despite the riskiness of this grenadelike death, many infections would be impossible to fight without it. Many bacteria and viruses need to live around or inside your cells to survive. When specialized sensors on your cells detect these threats, they can simultaneously activate your immune system and remove themselves as a home for pathogens. Researchers call this eliminating the niche[18] of the pathogen.

Cells die in many ways, including lysis.Inflammatory cell death plays a major role in pandemics. Yersinia pestis[19], the bacteria behind the Black Death, has evolved various ways of stopping human immune cells from mounting a response. However, immune cells developed the ability to sense this trickery and die an inflammatory death. This ensures that additional immune cells will infiltrate and eliminate the bacteria despite the bacteria’s best attempts to prevent a fight.

Although the Black Death is not as common nowadays, close relatives Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia enterocolitica are behind outbreaks of food-borne illnesses[20]. These infections are rarely fatal because your immune cells can aggressively eliminate the pathogen’s niche by inducing inflammatory cell death. For this reason, however, Yersinia infection can be more dangerous in immunocompromised people.

The virus behind the COVID-19 pandemic[21] also causes a lot of inflammatory cell death. Studies show that without cell death the virus would freely live inside your cells and multiply. However, this inflammatory cell death can sometimes get out of control and contribute to the lung damage[22] seen in COVID-19 patients, which can greatly affect survival. Researchers are still studying the role of inflammatory cell death in COVID-19 infection, and understanding this delicate balance can help improve treatments.

In good times and bad, your cells are always ready to sacrifice themselves to keep you healthy. You can thank cell death for keeping you alive.

References

- ^ sacrifice themselves to keep you healthy (nigms.nih.gov)

- ^ My own research (scholar.google.com)

- ^ divided into two types (www.the-scientist.com)

- ^ can make you sick (theconversation.com)

- ^ unnecessary inflammation (theconversation.com)

- ^ swaps out cells every day (doi.org)

- ^ Silent cell death, or apoptosis (www.genome.gov)

- ^ turn on executioner proteins (doi.org)

- ^ fingers and toes (embryo.asu.edu)

- ^ Michal Maňas/Wikimedia Commons (commons.wikimedia.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ resist apoptosis (www.mskcc.org)

- ^ autoimmune diseases (doi.org)

- ^ endometriosis (medlineplus.gov)

- ^ out-of-control growth in the uterus (doi.org)

- ^ inflammatory cell death (sitn.hms.harvard.edu)

- ^ tightly controlled (doi.org)

- ^ eliminating the niche (cshperspectives.cshlp.org)

- ^ Yersinia pestis (doi.org)

- ^ food-borne illnesses (edis.ifas.ufl.edu)

- ^ virus behind the COVID-19 pandemic (doi.org)

- ^ contribute to the lung damage (theconversation.com)

Authors: Zoie Magri, Ph.D. Candidate in Immunology, Tufts University