What is aphasia? An expert explains the condition forcing Bruce Willis to retire from acting

- Written by Swathi Kiran, Professor of Neurorehabilitation, Boston University

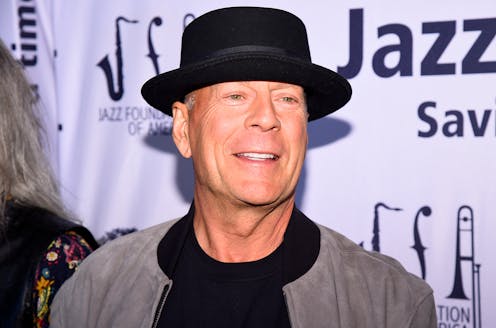

Actor Bruce Willis, 67, is “stepping away” from his career in film and TV[1] after being diagnosed with aphasia, his family announced on March 30, 2022.

In a message posted on Instagram[2], his daughter, Rumer Willis, said that the condition was “impacting his cognitive abilities.”

Swathi Kiran[3], director of the Aphasia Research Laboratory[4] at Boston University, explains what aphasia is and how it impairs the communication of those with the condition.

What is aphasia?

Aphasia[5] is a communication disorder that affects someone’s ability to speak or understand speech. It also impacts how they understand written words and their ability to read and to write.

It is important to note that aphasia can take different forms. Some people with aphasia only have difficulty understanding language – a result of damage to the temporal lobe[6], which governs how sound and language are processed in the brain. Others only have difficulty with speaking – indicating damage to the frontal lobe[7]. A loss of both speaking and comprehension of language would suggest damage to both the large temporal lobe and frontal lobe.

Almost everyone with aphasia struggles when trying to come up with the names of things they know, but can’t find the name for. And because of that, they have trouble using words in sentences. It also affects the ability of those with the condition to read and write.

What causes aphasia?

In most cases, aphasia results from a stroke or hemorrhage[8] in the brain. It can also be caused by damage to the brain from impact injury such as a car accident. Brain tumors can also result in aphasia.

There is also a separate form of the condition called primary progressive aphasia[9]. This starts off with mild symptoms but gets worse over time. The medical community doesn’t know what causes primary progressive aphasia. We know that it affects the same brain regions as in cases where aphasia results from a stroke or hemorrhage, but the onset of symptoms follow a different trajectory.

How many people does it affect?

Aphasia is unfortunately quite common. Approximately one-third of all stroke survivors[10] suffer from it. In the U.S., around 2 million people have aphasia and around 225,000 Americans[11] are diagnosed every year. Right now, we don’t know what proportion of people with aphasia have the primary progressive form of the condition.

There is no gender difference in terms of who suffers from aphasia. But people at higher risk of stroke – so those with cardiovascular disabilities and diabetes – are more at risk[12]. This also means that minority groups are more at risk, simply because of the existing health disparities in the U.S[13].

Aphasia can occur at any age. It is usually people over the age of 65 simply because they have a higher risk of stroke. But young people and even babies can develop the condition.

How is it diagnosed?

When people have aphasia after stroke or hemorrhage, the diagnosis is made by a neurologist. In these cases, patients will have displayed a sudden onset of the disorder – there will be a huge drop in their ability to speak or communicate.

With primary progressive aphasia, it is harder to diagnose. Unlike in cases of stroke, the onset will be very mild at first – people will slowly forget the names of people or of objects. Similarly, difficulty in understanding what people are saying will be gradual. But it is these changes that trigger diagnosis.

What is the prognosis in both forms of aphasia?

People with aphasia resulting from stroke or hemorrhage will recover over time. How fast and how much depends on the extent of damage to the brain, and what therapy they receive.

Primary progressive aphasia is degenerative – the patient will deteriorate over time, although the rate of deterioration can be slowed.

Are there any treatments?

The encouraging thing is that aphasia is treatable. In the non-progressive form, consistent therapy[14] will result in recovery of speech and understanding. One-on-one repetition exercises can help those with the condition regain speech. But the road can be long, and it depends on the extent of damage to the brain.

With primary progressive aphasia, symptoms of speech and language decline will get worse over time.

But the clinical evidence is unambiguous: Rehabilitation can help stroke survivors regain speech and the understanding of language and can slow symptoms[15] in cases of primary progressive aphasia.

Clinical trial of certain types of drugs are under way but in the early stages. There do not appear to be any miracle drugs. But for now, speech rehabilitation therapy is the most common treatment[16].

References

- ^ stepping away” from his career in film and TV (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ posted on Instagram (www.instagram.com)

- ^ Swathi Kiran (www.bu.edu)

- ^ Aphasia Research Laboratory (www.bu.edu)

- ^ Aphasia (www.mayoclinic.org)

- ^ temporal lobe (www.medicalnewstoday.com)

- ^ frontal lobe (www.medicalnewstoday.com)

- ^ aphasia results from a stroke or hemorrhage (www.stroke.org)

- ^ primary progressive aphasia (www.mayoclinic.org)

- ^ one-third of all stroke survivors (www.stroke.org.uk)

- ^ 2 million people have aphasia and around 225,000 Americans (www.aphasia.org)

- ^ more at risk (www.niddk.nih.gov)

- ^ existing health disparities in the U.S (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ consistent therapy (www.nidcd.nih.gov)

- ^ can slow symptoms (www.aphasia.org)

- ^ most common treatment (www.nidcd.nih.gov)

Authors: Swathi Kiran, Professor of Neurorehabilitation, Boston University