Why church conflict in Ukraine reflects historic Russian-Ukrainian tensions

- Written by J. Eugene Clay, Associate Professor of Religious Studies, School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, Arizona State University

As Russia amasses troops on the Ukrainian border[1] in preparation for a potential invasion, tensions between the two countries are also playing out through a conflict in the Orthodox Church.

Two different Orthodox churches[2] claim to be the one true Ukrainian Orthodox Church for the Ukrainian people. The two churches offer strikingly different visions of the relationship between the Ukrainian and the Russian peoples.

Two Orthodox churches

The religious history of Russia and Ukraine has fascinated me since I first visited Kyiv on a scholarly exchange in 1984. In my current research[3] I continue to explore the history of Christianity and the special role of religion in Eurasian societies and politics.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine[4] and annexed Crimea[5] in 2014, relations between the two countries have been especially strained. These tensions are reflected in the very different approaches of the two churches[6] toward Russia.

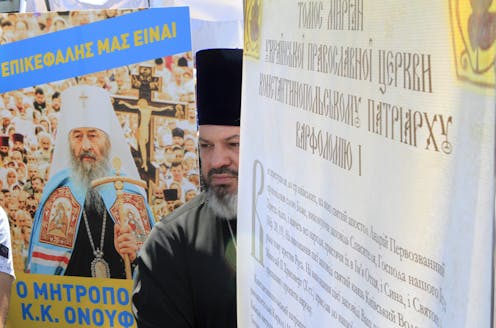

The older and larger church is the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Moscow Patriarchate[7]. According to Ukrainian government statistics, this church had over 12,000 parishes[8] in 2018. A branch of the Russian Orthodox Church, it is under the spiritual authority of Patriarch Kirill of Moscow. Patriarch Kirill[9] and his predecessor, Patriarch Aleksii II[10], both have repeatedly emphasized the powerful bonds that link the peoples of Ukraine and Russia.

By contrast, the second, newer church, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine[13], celebrates its independence from Moscow. With the blessing of the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople[14], a solemn council met in Kyiv in December 2018, created the new church, and elected its leader, Metropolitan Epifaniy[15]. In January 2019, Patriarch Bartholomew formally recognized[16] the Orthodox Church of Ukraine as a separate, independent and equal member of the worldwide communion of Orthodox churches.

Completely self-governing, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine was the culmination of decades of efforts by Ukrainian believers who wanted their own national church[17], free from any foreign religious authority. As an expression of Ukrainian spiritual independence, this new self-governing Orthodox Church of Ukraine has been a challenge to Moscow. In Orthodox terminology, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine claims autocephaly[18].

Unlike the Catholic Church, which has a single supreme spiritual leader in the pope, the worldwide Orthodox Church is divided into 14 universally recognized, independent, autocephalous or self-headed churches[19]. Each autocephalous church has its own head, or kephale in Greek. Every autocephalous church holds to the same faith as its sister churches. Most autocephalies are national churches, such as the Russian, Romanian and Greek Orthodox churches. Now, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine is claiming its place among the other autocephalous churches.

The Orthodox Church of Ukraine has over 7,000 parishes[20] in 44 dioceses. It regards Russians and Ukrainians as two different peoples, each of whom deserves to have its own separate church.

The independent Orthodox Church of Ukraine

The chief issue separating the Orthodox Church of Ukraine from the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Moscow Patriarchate is their relationship to the Russian Orthodox Church[21].

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Moscow Patriarchate has substantial autonomy in its internal affairs. Ultimately, however, it is subordinate to Patriarch Kirill[22] of Moscow, who must formally confirm its leader. The church emphasizes the unity that it enjoys with the Russian Orthodox believers.

By contrast, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine is independent of any other religious body. For the church’s proponents, this independence allows it to develop a unique Ukrainian expression of Christianity.

A common Orthodox Christian tradition

In both Russia and Ukraine, Orthodox Christianity is the dominant religious tradition. According to a 2015 Pew survey[23], 71% of Russians and 78% of Ukrainians identified themselves as Orthodox. Religious identity remains an important cultural factor in both nations.

Orthodox Christians in both Russia and Ukraine trace their faith back to the conversion[24] in A.D. 988 of the Grand Prince of Kyiv. Known as Vladimir by Russians and Volodymyr by Ukrainians, the pagan grand prince was baptized[25] by missionaries from Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. Kyiv became the most important religious center for the East Slavs.

Destroyed in 1240[26] by the Mongols[27], Kyiv fell into decline even as its northern neighbor, Moscow, became increasingly powerful. By 1686, Russia had conquered[28] eastern Ukraine and Kyiv. In that year, the patriarch of Constantinople formally transferred his spiritual authority over Ukraine to the patriarch of Moscow.

In the 20th century, a growing nationalist movement demanded Ukrainian independence for both the church[29] and the state. Although Ukraine became an independent country in 1991, its only universally recognized national Orthodox Church remained subject to Moscow.

Some Ukrainian Orthodox Christians tried to create an autocephalous church in 1921[30], 1942[31] and 1992[32]. These efforts largely failed. The churches that they formed were not recognized by the worldwide Orthodox community.

Ukrainian autocephaly

In April 2018 Petro Poroshenko[33], then the president of Ukraine, again tried to form an autocephalous Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

No fewer than three different churches[34] claimed to be the true Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Poroshenko hoped to unite these rival bodies.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Moscow Patriarchate was the largest church, and it enjoyed the recognition of the worldwide Orthodox community. However, it was and is subject to the Patriarch of Moscow[36] – an unacceptable status for many Ukrainians.

Two other churches, the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kyiv Patriarchate, had failed to gain recognition from other Orthodox churches.

Support for Ukrainian church

The ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople, Bartholomew I, supported Poroshenko’s project. As the leading bishop of the ancient capital of the Byzantine Empire, Bartholomew enjoys first place in honor[37] among all of the heads of the Orthodox churches.

Although Eastern Orthodox Christianity has no clear method of creating a new autocephalous church[38], Bartholomew argued that he had the authority to grant this status. Because Ukraine had originally received Christianity from the Byzantines, Constantinople was Kyiv’s mother church[39].

In December 2018 a unification council[40] formally dissolved the other branches of Orthodoxy in Ukraine and created the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. In January 2019, Bartholomew signed a formal decree[41], or tomos, proclaiming the new church autocephalous.

Support and rejection

So far, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine has received recognition[42] from four other autocephalous Orthodox churches. The churches of Constantinople, Alexandria, Greece and Cyprus[43] have each welcomed the new church.

Three other autocephalous churches have explicitly rejected[44] the new church. The Moscow[45] Patriarchate even broke communion[46] with Constantinople over its role in creating the new church.

Nadieszda Kizenko, a leading historian of Orthodoxy, has said that Bartholomew has shattered Orthodox unity[47] to create a church of dubious legitimacy.

By contrast, the noted theologian Cyril Hovorun[48] greeted the Orthodox Church of Ukraine as a positive “demonstration of solidarity with … the Ukrainian people who suffered from the Russian aggression[49].”

[Explore the intersection of faith, politics, arts and culture. Sign up for This Week in Religion.[50]]

Two visions of history

Today, the two major rival expressions of Orthodoxy in Ukraine reflect two different historical visions of the relationship between Russians and Ukrainians.

For the Moscow Patriarchate, Russians and Ukrainians are one people. Therefore a single church should unite them.

President Vladimir Putin of Russia has made this very argument in a recent essay[51]. He characterizes the Orthodox Church of Ukraine as an attack on the “spiritual unity” of the Russian and Ukrainian peoples.

The Orthodox Church of Ukraine holds a very different view. In an interview[52] with the British Broadcasting Corp., Metropolitan Epifaniy firmly rejected “Russian imperial traditions.” As a separate people with a unique culture, Ukrainians require an independent church.

The future of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine is unclear. It enjoys the support of several of its sister churches. At the same time, it faces fierce opposition from Moscow. For now, it remains a source of controversy between Russia and Ukraine.

References

- ^ Russia amasses troops on the Ukrainian border (www.cnn.com)

- ^ Two different Orthodox churches (www.degruyter.com)

- ^ research (asu.academia.edu)

- ^ Russia invaded Ukraine (doi.org)

- ^ annexed Crimea (brill.com)

- ^ churches (doi.org)

- ^ Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Moscow Patriarchate (www.academia.edu)

- ^ 12,000 parishes (doi.org)

- ^ Patriarch Kirill (doi.org)

- ^ Patriarch Aleksii II (doi.org)

- ^ Presidential Administration of Ukraine (upload.wikimedia.org)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Orthodox Church of Ukraine (doi.org)

- ^ Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople (doi.org)

- ^ Metropolitan Epifaniy (www.rferl.org)

- ^ recognized (www.wsj.com)

- ^ national church (www.cornellpress.cornell.edu)

- ^ autocephaly (www.britannica.com)

- ^ autocephalous or self-headed churches (doi.org)

- ^ 7,000 parishes (www.pomisna.info)

- ^ Russian Orthodox Church (www.jstor.org)

- ^ subordinate to Patriarch Kirill (doi.org)

- ^ 2015 Pew survey (www.pewresearch.org)

- ^ trace their faith back to the conversion (www.jstor.org)

- ^ the pagan grand prince was baptized (www.jstor.org)

- ^ Destroyed in 1240 (www.jstor.org)

- ^ Mongols (www.jstor.org)

- ^ Russia had conquered (doi.org)

- ^ growing nationalist movement demanded Ukrainian independence for both the church (www.jstor.org)

- ^ tried to create an autocephalous church in 1921 (doi.org)

- ^ 1942 (www.jstor.org)

- ^ 1992 (www.jstor.org)

- ^ Petro Poroshenko (www.yalejournal.org)

- ^ three different churches (emerging-europe.com)

- ^ Maxym Marusenko/NurPhoto via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ subject to the Patriarch of Moscow (doi.org)

- ^ first place in honor (www.rivisteweb.it)

- ^ no clear method of creating a new autocephalous church (www.mdpi.com)

- ^ mother church (risu.ua)

- ^ unification council (www.degruyter.com)

- ^ signed a formal decree (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ received recognition (doi.org)

- ^ Cyprus (www.ukrweekly.com)

- ^ explicitly rejected (doi.org)

- ^ Moscow (doi.org)

- ^ broke communion (www.sciendo.com)

- ^ shattered Orthodox unity (berkleycenter.georgetown.edu)

- ^ Cyril Hovorun (www.sanktignatios.org)

- ^ demonstration of solidarity with … the Ukrainian people who suffered from the Russian aggression (berkleycenter.georgetown.edu)

- ^ Sign up for This Week in Religion. (theconversation.com)

- ^ essay (en.kremlin.ru)

- ^ interview (www.bbc.com)

Authors: J. Eugene Clay, Associate Professor of Religious Studies, School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, Arizona State University