West Elm Caleb and the rise of the TikTok tabloid

- Written by Jenna Drenten, Associate Professor of Marketing, Loyola University Chicago

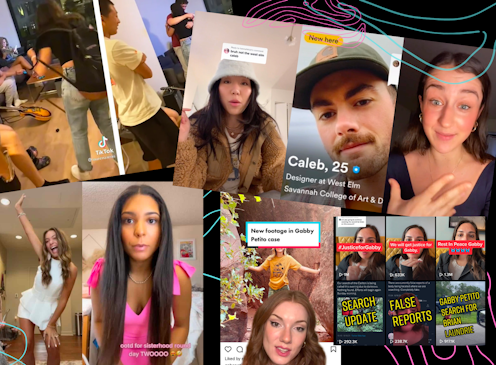

Can you believe Makayla was dropped from Bama Rush[1]? Do you think Couch Guy[2] was cheating? Did you see Gabby Petito’s[3] last post before she went missing?

If you don’t spend much time online, you may not recognize these names. But on TikTok, their stories became sensationalized, memeified, hashtagged and rehashed.

The most recent is “#WestElmCaleb[4].” Women took to TikTok to share their experiences of being peppered with affection[5], strung along and ultimately ghosted by a New York City-based designer named Caleb, who became the exemplar for the worst aspects of online dating culture.

Together, these stories represent the emergence of what I call the “TikTok tabloid,” in which users collectively manufacture and dramatize stories like an investigative gossip reel. Traditional tabloids place the lurid limelight on celebrities and public figures. But the TikTok tabloid targets everyday people.

How did we get to the age of the TikTok tabloid? As someone who studies digital consumer culture[6], I see it as an outgrowth of the dynamics of social surveillance[7]: using digital technologies to keep a close watch on one another, while producing online content in anticipation of being watched.

Shocking! Exclusive! Scoop!

Tabloid journalism isn’t new. Common tabloid genres[8] of stars, sex, scandals and slayings have been cultural guilty pleasures since the early 1900s.

In the U.S., early tabloid newspapers like The Daily Mirror and New York Daily News ushered in an era of sensationalist reporting. These papers were particularly popular among working class readers[9] who reveled in the speculative shenanigans of high society.

In the 1970s, glossy tabloid magazines like People and Us Weekly picked up the helm with behind-the-scenes celebrity exclusives and human-interest stories. Tabloid journalism migrated to the small screen[11] in the 1990s with television shows like “Hard Copy” and “Inside Edition.”

And in the 2000s, the internet churned out round-the-clock celebrity gossip[12] with clickbait headlines on websites like TMZ.com and PerezHilton.com.

Previous eras of tabloid journalism were marked by highly curated content[13] with a focus on lifestyles of the rich and famous. The brokers of attention were editors, publishers, paparazzi, journalists and publicists[14]. Tabloids filtered information to the masses, and in turn the masses influenced celebrity behaviors.

But now we are witnessing a new iteration of tabloidization playing out in real time on TikTok, where digital technologies enable everyday consumers to play the roles of armchair experts, investigative reporters, digital paparazzi, talking heads and celebrities themselves.

Watching and being watched

Traditional tabloid journalism is predicated on surveillance dynamics of “the many watching the few[15]”: an obsession with a relative handful of selected stars and scandals. The emergent TikTok tabloid relies on dynamics of social surveillance, or “the many watching the many[16]” – a network of everyday people watching and being watched.

According to media scholar Alice E. Marwick, social surveillance[17] is defined as “the ongoing eavesdropping, investigation, gossip, and inquiry that constitutes information gathering by people about their peers, made salient by the social digitization normalized by social media.”

Classic views of surveillance envision a prison state – a Big Brother-esque panopticon[18] where a guard in a tower can watch prisoners in cells but the prisoners in the cells cannot see into the tower.

In social surveillance, everyone online is both a guard and a prisoner, constantly consuming online content and producing content for others to see.

This always-on dynamic works to control behavior. Everyday people have the power to orchestrate what other users see, read and believe – not only about traditional celebrities, but also about regular everyday people.

In the case of Gabby Petito, who went missing in September 2021, TikTokers developed theories[19] about her disappearance based on her final Instagram post and her Spotify playlists, claimed to psychically track her[20] and scrambled to be the first to report #GabbyPetito[21] breaking news.

Such deep-diving into people’s private lives for public entertainment is a function of social surveillance only further accelerated by the interactive features of TikTok.

‘Like for part two’

TikTok’s unique features and storytelling culture make it the perfect social media platform for making everyday people fodder for tabloid-like coverage.

First, interactive features of the platform allow TikTokers to collectively contribute to the TikTok tabloid in real time. TikTokers can directly respond to comments[22] with new videos, curate and follow content via hashtags[23] and sounds[24], stitch[25] videos together with other content, caption them[26] for context, and use a green screen[27] effect – just like a real news studio.

Second, TikTok’s algorithm[28] serves users content based on a combination of their interests and what seems to be generally trending. Watching a few videos about West Elm Caleb easily triggers a stream of West Elm Caleb content on the “for you page[29],” or #FYP: the TikTok version of front page news.

Third, storytelling practices on the TikTok platform mimic exclusive reports, hot takes and cliffhanger media. TikTokers dangle tantalizing bits of stories in front of viewers with caveats of “like for part 2” or by serializing their content. These stories then take on lives of their own, becoming culturally embedded memes[30].

Social media can be a useful mechanism for accountability[31]. On Twitter, for example, users voiced outrage over racist actions of the Central Park Karen[32] and found solidarity in sharing experiences of sexual harassment through the #MeToo Movement[33].

But where platforms like Twitter, Instagram and Facebook enable users to tell stories, TikTok enables users to create full-fledged narrative rabbit holes. A nugget of content can be collectively transformed into an epic drama.

The promise and peril of publicity

The TikTok tabloid democratizes access to fame while fueling America’s cultural penchant for gossip[34].

The TikTok tabloid may seem fun and frivolous – an entertaining live action, participatory role-play[35] version of TMZ playing out in real time. But there can a dark side to this form of public shaming[36] and internet sleuthing[37].

The constant churn of sensational news can take a toll on well-being[38], particularly for those most directly involved[39]. In November 2021, Sabrina Prater[40] became unwitting front-page news of the TikTok tabloid when her mundane dancing video spiraled into conspiracy theories of being a serial killer. She later posted a tearful video pleading for the emotional attacks to stop.

[Over 140,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today[41].]

In contrast to traditional celebrities, few everyday people have publicists, spin doctors[42] and social media managers who can help them handle the stresses of scrutiny[43].

Who manages the public images of people who didn’t choose to become public figures?

It would be easy to say they should just stay off TikTok. But it’s not that simple. Social surveillance ensures we all have the potential to become headline news – beholden to the TikTok tabloid taste-makers.

References

- ^ Bama Rush (www.refinery29.com)

- ^ Couch Guy (www.cnet.com)

- ^ Gabby Petito’s (www.insider.com)

- ^ #WestElmCaleb (www.tiktok.com)

- ^ peppered with affection (www.huffpost.com)

- ^ digital consumer culture (jennadrenten.com)

- ^ social surveillance (ojs.library.queensu.ca)

- ^ Common tabloid genres (www.worldcat.org)

- ^ working class readers (doi.org)

- ^ Spencer Platt/Newsmakers via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ migrated to the small screen (www.taylorfrancis.com)

- ^ round-the-clock celebrity gossip (www.colorado.edu)

- ^ highly curated content (www.google.com)

- ^ and publicists (doi.org)

- ^ the many watching the few (doi.org)

- ^ the many watching the many (thesocietypages.org)

- ^ social surveillance (ojs.library.queensu.ca)

- ^ a Big Brother-esque panopticon (books.google.com)

- ^ developed theories (www.vice.com)

- ^ psychically track her (www.insider.com)

- ^ #GabbyPetito (www.tiktok.com)

- ^ respond to comments (newsroom.tiktok.com)

- ^ hashtags (boosted.lightricks.com)

- ^ sounds (www.tiktok.com)

- ^ stitch (newsroom.tiktok.com)

- ^ caption them (newsroom.tiktok.com)

- ^ green screen (newsroom.tiktok.com)

- ^ TikTok’s algorithm (later.com)

- ^ for you page (www.tiktok.com)

- ^ becoming culturally embedded memes (doi.org)

- ^ can be a useful mechanism for accountability (doi.org)

- ^ Central Park Karen (www.bet.com)

- ^ #MeToo Movement (muse.jhu.edu)

- ^ cultural penchant for gossip (library.oapen.org)

- ^ participatory role-play (www.researchgate.net)

- ^ public shaming (www.vox.com)

- ^ internet sleuthing (mastersofmedia.hum.uva.nl)

- ^ well-being (www.amity.edu)

- ^ directly involved (slate.com)

- ^ Sabrina Prater (www.rollingstone.com)

- ^ Sign up today (memberservices.theconversation.com)

- ^ spin doctors (doi.org)

- ^ the stresses of scrutiny (doi.org)

Authors: Jenna Drenten, Associate Professor of Marketing, Loyola University Chicago

Read more https://theconversation.com/west-elm-caleb-and-the-rise-of-the-tiktok-tabloid-175485