Young Jazz, Old Jazz, Our Jazz, My Jazz

- Written by John Armato

When I think of myself as a jazz musician who will turn 58 this year, it’s a little startling to realize I will have been around just about half as long as jazz itself. That assumes you go with 1917 as jazz’s birthday. Most commonly, jazz historians pick February 26, 1917 when asked to fix the music’s origins in time. That was the date the Original Dixieland Jass (yes, “jass”) Band recorded “Livery Stable Blues,” believed to be the first jazz recording. Of course, it’s not as if there was no sign of jazz on February 25, 1917. The stew had been simmering for a while.

Birthdate aside, I can never decide if jazz is old or young. I mean, on the one hand … 105 years. But on the other, my dad was born in 1928, just 11 years after that first recording. So his parents’ generation knew a good stretch of time before jazz was born; he was around for its childhood; and here I am – just three generations in – still watching it grow up.

Regardless, after something’s been around for a hundred years or so, people start to assess its “impact on culture.” So, what has jazz wrought in its 105 years?

It has been called “the only true American art form.” The “only” part of that is a speed bump, though. Slow down and ask aficionados about rock ’n’ roll, for example, and prepare for a lengthy and worthy debate. And even “American” is likely to stir controversy. Like some cars, jazz may have been assembled here, dissenters will say, but the parts were made overseas.

Jazz has been called a union of African rhythms and European harmonies. But that is a simplification. Put your hands deeper into jazz soil and you’ll eventually touch island roots as well. For 300 years the slave trade triangle made stops in Europe, Africa, and America by way of the Caribbean islands. For whatever reason, the influence of the islands on jazz isn’t talked about as much.

In the 80s, Dr. Billy Taylor, the late jazz pianist, composer, and educator, notably called jazz “America’s classical music.” It’s a description that would appear to transcend debates about race and appropriation, mainly by ignoring them. It’s also a description that, through its use of “classical,” appears to lift jazz out of the gutter and with it, perceptions of jazz as music of disrepute.

Ted Gioia called this one. The musician, critic, historian, and author of “Music: A Subversive History,” makes the point that going back even to ancient times, music of all types begins on the fringes of society – in disrepute of some sort – but over time becomes co-opted by the establishment.

I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing, as the establishment’s imprimatur gives practitioners of an art form more opportunities. But it also imposes more expectations – constraints, really – and less tolerance for experimentation, the very thing that led to its development way back there on the fringe …

We know the date of jazz’s conversion to respectability too, by the way: January 16, 1938. That’s when Benny Goodman delivered the first concert of “popular music” ever to be held at Carnegie Hall. (Keep in mind, jazz and big band music was popular music in 1938.) I’ve always thought the date was especially fitting since jazz was just preparing to turn 21, as if reaching adulthood.

Jazz was becoming fully woven into the cultural fabric. In 1949, Louis Armstrong became the first jazz musician to be featured on the cover of Time Magazine. White pianist Dave Brubeck more or less invented the college concert tour in the 50s and then, in 1960, cancelled a 25-date tour of colleges and universities throughout the South after 22 schools refused to allow his black bassist, Eugene Wright, to perform. The State Department put Armstrong, Brubeck, and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie to work as musical Cold War weapons with international tours designed to export the sound of American freedom to communists around the world in an attempt to temper their ideological exports.

Jazz clubs and festivals exploded throughout the 50s, 60s, and 70s, but what, until then, had been one of the most profound artistic channels of creative expression, racial reckoning, and badge of American honor, wavered and waned by the 80s. Heavily commercialized forms of jazz dominated the popular airwaves (think Kenny G). At the same time, the young and immensely talented trumpeter, Wynton Marsalis, sounded the call for a return to tradition and respect. (Among other things, he insisted his band appear on stage in suit and tie). Like so many art forms that mature and fragment into various movements, jazz got better and it got worse. It depends on who you ask, where you look, and what you expect.

The most pervasive impact jazz has had on culture may be the diversity of opinions it inspires. Like asking two New Yorkers the best way to get downtown from Central Park, if you’re not careful, the main thing you’ll remember is the debate.

Today, as jazz faces far more years ahead of it than I have ahead of me, (I’m not pessimistic about my longevity; I’m just optimistic about jazz’s) I’m less interested in the debate. I know how jazz has affected me, a “culture of one,” if you will, and that’s enough.

Jazz was my first encounter with beauty.

I really don’t know how else to say it. There’s no explaining the x-factor inside of us that resonates like a plucked string when we hear this but not that. It was listening to jazz that created my first transcendent moments, when time stopped, and a sublime sense of pleasure permeated me, and I realized that things outside of us could create experiences inside of us that somehow made everything else better around us.

As a school kid of the 70s, when my peers were listening to AC/DC, jazz made me an outsider, but I didn’t care. When I was in junior high, nearly every day after school I would go home, lie on the couch, and listen to Dave Brubeck’s “Jazz Goes to College” album. That music was the greatest thing in the world as far as I was concerned. And it still is.

I don’t know if we can ask something to have more impact than that on us as individuals, or as a culture. Anything that brings something beautiful into a life or lives needs no defense, explanation, or deeper meaning. Beauty is its own reward, and beauty is where you find it. I found it in jazz.

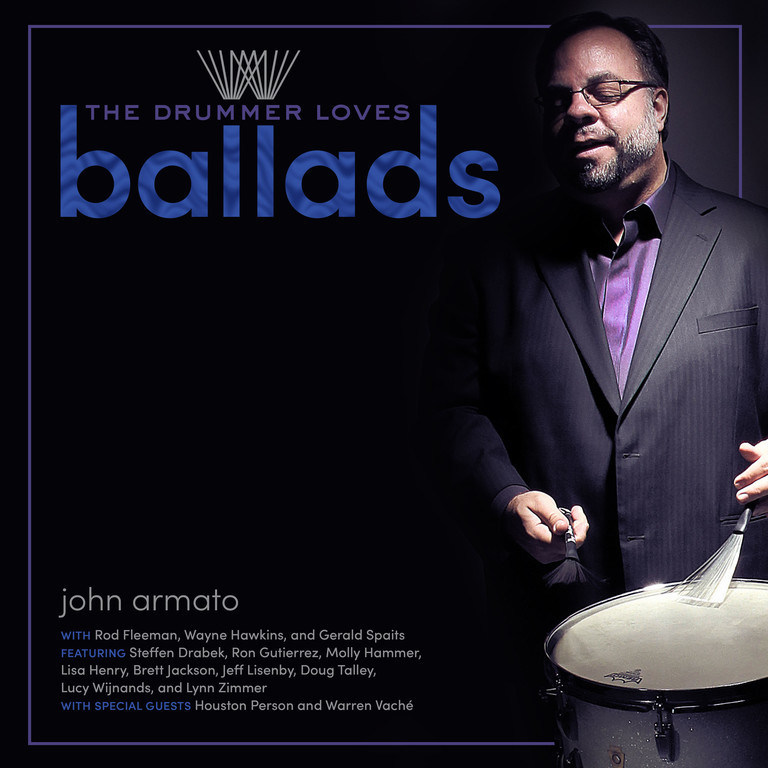

John Armato is a jazz drummer, writer, designer, and speaker. A Kansas City native, New York City ex-pat, and now Sacramento resident, Armato was 17 when he played his first jam session. Forty years later that session is recalled in the opening track of Armato’s recently released debut album, “The Drummer Loves Ballads.” From intimate quartet settings to sweeping orchestral arrangements, “The Drummer Loves Ballads” features more than 25 musicians, including the legends Houston Person and Warren Vaché. It is a unique, full-album listening experience, now available at TheDrummerLovesBallads.com and everywhere you buy, download or stream your music.