How 2 Jewish soldiers' court-martials put a spotlight on antisemitism and racism

- Written by Jeannette Gabriel, Director, Schwalb Center for Israel and Jewish Studies, University of Nebraska Omaha

In October 2021, a new museum[1] opened in Paris, dedicated to the famous “Dreyfus affair.”

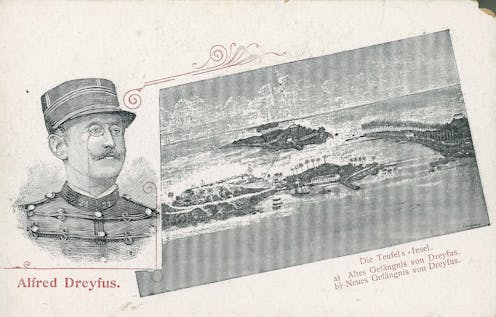

Alfred Dreyfus[2] was a Jewish captain in the French army who was court-martialed and convicted of treason on flimsy evidence in 1894 – then exonerated in 1906, after years of high-profile court proceedings and public debate that divided the country.

His sensational case put deep-seated antisemitism[3] in the spotlight and influenced French politics[4] for years to come. Even today[5], it is a global symbol of discrimination and injustice.

Another high-profile example of a Jewish soldier being court-martialed happened here in the United States. Though less famous than the Dreyfus affair, the case of Al Levy also centered around discrimination, against both Jewish and African American members of the military – and helped bring lasting change.

‘L'affaire’

The Dreyfus scandal began with Alfred Dreyfus being accused of selling military secrets to the German government and sentenced to life in prison.

From the start, antisemitism surrounded the trial. Dreyfus’ loyalty to the French government was challenged in the media, with suggestions that he was part of an international Jewish conspiracy. Many newspapers ran cartoons filled with antisemitic stereotypes[6].

He was held for five years in a brutal penal colony called Devil’s Island[7], off the coast of South America. During that time, support for Dreyfus grew, as it became clear how thin the evidence against him was, and pressure mounted for his release.

The most famous person that brought attention to Dreyfus’ plight was a leading French thinker and writer, Emile Zola[8]. Zola published an open letter[9] that accused the government and the military of systematic antisemitism. As Zola hoped, the letter[10] resulted in libel charges against him, bringing widespread attention to the case.

British writer Michael Rosen argues[11] Zola’s intervention made it legitimate to speak out against antisemitism for the first time in France, and brought public attention to how nationalism and antisemitism limited the legal system’s ability to deliver justice. The case became a critical moment that divided France, forcing the country to confront deeply ingrained antisemitism[12] and uphold impartial justice.

Dreyfus was convicted a second time after a retrial in 1899, but granted a pardon by the president and released from prison. He was not fully exonerated until 1906. Some of the documents used to convict him were later found to be forgeries[13].

An American court-martial

As a scholar, I explore points of commonality and conflict between Jewish and African American communities and uncover unknown stories of marginalized groups. My research[14] examines how previous generations have challenged antisemitism and racism, and what we can learn to confront the same issues today.

My recent work[15] examines the court-martial of Al Levy, a Jewish American soldier who was stationed at the Lincoln, Nebraska airfield[16] during World War II. Levy was popular with his fellow soldiers for writing funny and romantic songs about life in the Army. In early 1943, he became upset over the way African American soldiers on the base were being mistreated and raised concerns with his fellow soldiers and commanding officers, as well as friends in New York City.

The U.S. military court-martialed him[17] in the summer of 1943. The military claimed that he was not being punished for his critiques of the military’s discriminatory policies towards African American soldiers, but for making negative statements about his commanding officer and engaging in conduct unbecoming an officer[18]. He was assigned to hard labor, stripped of his rank and had his pay decreased. During his trial, the military prosecutors highlighted his Jewish identity and labor activism, and questioned his loyalty to the American government.

Several newspapers brought attention to Levy’s case, including a popular New York daily, “PM.” His supporters argued that he had been targeted because he was Jewish, and demanded equal treatment within the military[19].

His father sent a personal appeal to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944 asking him to review his son’s case. Morris Levy pointed out his son was suffering because he defended American citizens who were being mistreated and asked whether the U.S. military was different than the Nazis in Germany.

A segregated military

During World War II all of the U.S. military was segregated, even if bases were located outside of the Jim Crow[21] South. African American soldiers at the Lincoln Airfield and other military bases faced routine discrimination and poor treatment.

As a result of the Levy court-martial, the Lincoln branch of the NAACP, the oldest civil rights organization in the U.S., conducted an investigation[22] of African American soldiers at the airfield. Their report documented inferior housing and recreation opportunities and pay inequality. The African American soldiers reported that they had been taken to help with the local harvest and, unlike white peers, were not paid. They were expected to “act as a worker slave for the white man.”

Levy’s supporters[23] critiqued the military’s response as antisemitic[24] and demanded not just that he be released and his status restored, but also an end to segregation within the military. His case received national attention from African American and Jewish civil rights groups and labor unions. Thousands of protest letters and petitions were written and public meetings held to demand Levy’s release[25] and exoneration.

The NAACP told Roosevelt that Levy’s court martial was negatively affecting African American morale within both the military and civilian population. The Congress of Industrial Organizations, which represented 3.3 million workers[26], brought up the Levy case at their national convention. They linked the military’s mistreatment of him directly to broader concerns over African American discrimination.

The government responded to this widespread public pressure campaign by quietly releasing Levy[27] for good behavior and restoring his rank by the end of the war.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter[28].]cc

Civil rights victory

After the war, President Harry Truman responded to growing calls for civil rights by issuing Executive Order 9981[29] in 1948, which set up a committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Services.

African American, Jewish and labor organizations were frustrated with the limited work of the committee, however, and set up their own public hearings[30]. Veterans, including Levy, testified at these highly publicized meetings in cities across the country. This public activism contributed to the elimination of military segregation by the end of the Korean War[31] in 1953.

Like Zola, Levy took personal risks to bring widespread public attention to antisemitism and racism – a reminder that individual acts of solidarity by people who are not directly affected by systemic racism themselves can have a powerful impact.

References

- ^ new museum (www.maisonzola-museedreyfus.com)

- ^ Alfred Dreyfus (www.britannica.com)

- ^ antisemitism (theconversation.com)

- ^ influenced French politics (www.bloomsbury.com)

- ^ Even today (www.newyorker.com)

- ^ cartoons filled with antisemitic stereotypes (collections.ushmm.org)

- ^ Devil’s Island (www.britannica.com)

- ^ Emile Zola (www.bloomsbury.com)

- ^ an open letter (jean-max-guieu.facultysite.georgetown.edu)

- ^ the letter (histoire-image.org)

- ^ Michael Rosen argues (www.faber.co.uk)

- ^ deeply ingrained antisemitism (doi.org)

- ^ found to be forgeries (www.dreyfus.culture.fr)

- ^ My research (www.unomaha.edu)

- ^ recent work (docs.lib.purdue.edu)

- ^ Lincoln, Nebraska airfield (mynehistory.com)

- ^ court-martialed him (books.google.com)

- ^ unbecoming an officer (www.nli.org.il)

- ^ Jewish, and demanded equal treatment within the military (www.idaillinois.org)

- ^ Library of Congress/Corbin Historian via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ Jim Crow (onlinellm.usc.edu)

- ^ an investigation (catalog.loc.gov)

- ^ Levy’s supporters (chroniclingamerica.loc.gov)

- ^ as antisemitic (www.idaillinois.org)

- ^ demand Levy’s release (www.nli.org.il)

- ^ which represented 3.3 million workers (www.nber.org)

- ^ quietly releasing Levy (timesmachine.nytimes.com)

- ^ Sign up for our weekly newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ Executive Order 9981 (www.archives.gov)

- ^ their own public hearings (archives.nypl.org)

- ^ Korean War (koreanwarlegacy.org)

Authors: Jeannette Gabriel, Director, Schwalb Center for Israel and Jewish Studies, University of Nebraska Omaha