Shutting down school vaccine clinics doesn't protect minors – it hurts people who are already disadvantaged

- Written by Katherine A. Foss, Professor of Media Studies, Middle Tennessee State University

A 1918 newspaper article[1] captures public attitudes toward a typhoid vaccine clinic at the Oakdale schoolhouse in Louisville, Kentucky. “Everybody comes – railroad men, children, young girls, old people, housewives,” it reads, “all with sleeves that roll up and arms ready for the brief stick with the fine needle.”

Until recently, school-located vaccination clinics, or SLVs, have been applauded, or simply taken for granted[2]. That changed in mid-July of 2021, when Tennessee halted COVID-19 vaccination clinics on school property[3]. The decision was part of a broader effort to cease vaccine messages geared toward children and adolescents. The pause lasted only 10 days and has since been somewhat reversed[4], limiting vaccine promotion to messages geared at parents and holding some vaccine events on school property.

Those who want to eliminate school-located COVID-19 vaccination clinics say the sites exist to immunize children without parental consent. However, even before the Food and Drug Administration expanded eligibility to include 12-to-15-year-olds, school-located sites offered COVID-19 vaccines to school staff and other eligible adults.

I am an expert on the history of epidemics[5], and my research shows that this current move is an unprecedented detour from schools’ historical promotion of routine vaccines. Preventing school vaccination clinics does not keep waves of teenagers from getting immunized without consent. Rather, it penalizes those who want to get vaccinated but struggle with access.

Partisan divide

Tennessee’s “pause” stemmed from the Republican Party’s resistance[6] to publicly embracing COVID-19 vaccination, paired with overhyped attention to the Mature Minor Doctrine[7].

The Mature Minor Doctrine is a Tennessee law allowing “medical treatment and vaccinations to patients as young as 14,” enabling adolescents to make decisions[8] about their own health. It is especially useful for those who don’t live with their parents, are in situations of neglect or abuse or face emergency circumstances. However, it also covers preventive health care and treatment including vaccinations. Many states hold similar consent exceptions.

Whether minors can get the COVID-19 vaccination without parental approval has varied by city and state[9]. After the Pfizer vaccine’s emergency authorization expanded to include ages 12 to 15, news coverage[10] called attention to teenagers receiving COVID-19 vaccines without consent, in some cases questioning the practice without addressing its prevalence or the risk of not immunizing this age group[11]. In Tennessee, the public health department has stated that only eight adolescents[12] had received a COVID-19 vaccine without parental consent. Furthermore, no evidence has suggested that SLVs have contributed to these cases.

In other words, misplaced ideology, not data on teenagers getting vaccinated without consent, has been the driving force against SLVs, including COVID-19 vaccine clinics at schools.

From smallpox to HPV

Since the mid-19th century, schools have been common sites for vaccine clinics to respond to outbreaks and also provide catch-up immunizations.

In 1875, 17,505 children[13] were immunized against smallpox in New York City school clinics. Temporary typhoid vaccine clinics[14] emerged in the 1910s and 1920s across the U.S. And the 1954 polio vaccine field trials took place at 15,000 public schools[15] across 44 states.

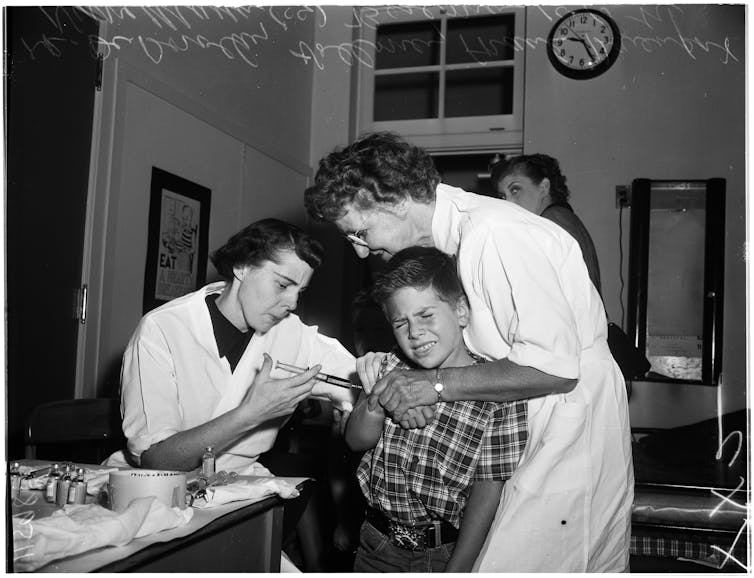

A boy is injected with polio vaccine at a school, circa 1955.

USC Libraries/Corbis Historical Collection via Getty Images[16]

A boy is injected with polio vaccine at a school, circa 1955.

USC Libraries/Corbis Historical Collection via Getty Images[16]

Even before Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine received approval in April 1955, SLVs were scheduled in anticipation[17]. They became the main locations for children to receive their vaccines. In the 1960s, SLVs across the country hosted “Sabin Sundays,” providing the oral polio vaccine developed by Albert Sabin to any unvaccinated adult or child[18]. During this time, school campaigns also expanded to offer immunizations against rubella and measles[19].

Since then, SLVs have continued to be used for public health outreach, protecting children against hepatitis B, seasonal influenza and HPV. Many sites emerge for a short window each year, providing catch-up immunizations[20] for kids who are behind on other vaccines as well as shots against seasonal flu. Others spring up as needed, as demonstrated with H1N1 immunizations in 2009. Even the pop-up clinics at schools typically require parental consent for participation.

Moreover, SLVs are often available to whole communities – not just school attendees. They are widely effective in addressing disparities in immunization[21] linked to income and insurance status. Like other mass vaccination sites, SLVs can immunize large numbers of people in a short period of time and reduce disease in a community[22].

They have additional benefits[23], too. SLVs are convenient for families and school staff, provide a large, temperature-controlled space, create awareness of the importance of vaccines and boost rates of completion[24] for vaccines given in a series.

Pandemic disruptions

The COVID-19 pandemic caused global disruptions in children’s vaccinations. In 2020, routine vaccinations decreased[25] because of stay-at-home orders, delay or cancellation of immunization programs[26] and other reasons connected to the global health crisis.

For the diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis vaccines, known as DTaP, New York City experienced a decrease of 16% for children under 2 and 60% for ages 2 to 6[27]. Researchers estimate that routine vaccinations need to increase as much as 15%[28] for vaccine rates to return to pre-pandemic levels.

A nurse gives a 3-year-old a flu shot at a mobile immunization clinic set up behind John Ruhrah Elementary/Middle School in Baltimore in October 2020.

Katherine Frey/The Washington Post via Getty Images[29]

A nurse gives a 3-year-old a flu shot at a mobile immunization clinic set up behind John Ruhrah Elementary/Middle School in Baltimore in October 2020.

Katherine Frey/The Washington Post via Getty Images[29]

It’s important to remember that vaccine-preventable diseases are not distant memories. Only smallpox has been globally eradicated – polio, diphtheria, rubella and other dangerous viruses still exist.

Vaccination reductions can produce costly community outbreaks. A single measles case in 2018 erupted into over 600 cases[30] in an undervaccinated community in New York, costing US$8.4 million in public health response efforts, medical expenses and productivity loss. Similarly, Washington state’s 2019 Clark County measles outbreak[31] cost an estimated $3.4 million.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter[32].]

SLVs for COVID-19

Starting in March 2020, schools across the country began offering COVID-19 vaccines – first for staff and community members, and in May for those ages 12 and up. Such sites have been especially important[33] for low-income and other underserved communities[34] significantly affected by the pandemic.

Once the eligible age expands to include children ages 11 and younger, school vaccine clinics can serve entire families. The White House has encouraged[35] every school district to host at least one pop-up vaccination clinic. As with the typhoid and polio clinics before them, the intention is to curb the spread of disease and improve overall public health – the message that should underscore all vaccination decisions for this pandemic.

References

- ^ A 1918 newspaper article (www.newspapers.com)

- ^ simply taken for granted (doi.org)

- ^ halted COVID-19 vaccination clinics on school property (www.tennessean.com)

- ^ somewhat reversed (www.tennessean.com)

- ^ expert on the history of epidemics (scholar.google.com)

- ^ Republican Party’s resistance (www.kff.org)

- ^ Mature Minor Doctrine (www.tn.gov)

- ^ decisions (mckinneylaw.iu.edu)

- ^ varied by city and state (www.kff.org)

- ^ news coverage (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ risk of not immunizing this age group (www.tennessean.com)

- ^ eight adolescents (www.tennessean.com)

- ^ 17,505 children (doi.org)

- ^ typhoid vaccine clinics (www.newspapers.com)

- ^ 15,000 public schools (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ USC Libraries/Corbis Historical Collection via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ SLVs were scheduled in anticipation (www.newspapers.com)

- ^ adult or child (ohiomemory.org)

- ^ rubella and measles (www.newspapers.com)

- ^ providing catch-up immunizations (www.newspapers.com)

- ^ disparities in immunization (www.doi.org)

- ^ reduce disease in a community (doi.org)

- ^ additional benefits (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ boost rates of completion (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ routine vaccinations decreased (www.who.int)

- ^ delay or cancellation of immunization programs (www.who.int)

- ^ 16% for children under 2 and 60% for ages 2 to 6 (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ as much as 15% (doi.org)

- ^ Katherine Frey/The Washington Post via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ over 600 cases (www.nejm.org)

- ^ 2019 Clark County measles outbreak (doi.org)

- ^ Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ especially important (doi.org)

- ^ low-income and other underserved communities (edsource.org)

- ^ White House has encouraged (www.nytimes.com)

Authors: Katherine A. Foss, Professor of Media Studies, Middle Tennessee State University